Zusammenfassung

Während der Nachgrabungen im Jahr 2008 wurde im Abraum vor der Vogelherdhöhle ein Wildschweinzahn gefunden, der klare Bearbeitungsspuren aufweist. Neben der Politur, die auch auf natürliche Weise auf Wildschweinhauern entstehen kann, zeigt das Artefakt Zeichen von schneidender oder schabenden Tätigkeit und Politur, die nach dem Tod des Tieres entstanden sein müssen. Die Form der Figur ähnelt einer magdalénienzeitlichen Frauenfigurine, mit einem herausgestellten Gesäß und einem stabförmigen Körper. Dies führte zu der Hypothese, dass es sich bei dem Artefakt um eine Frauenstatuette handeln könnte. Eine alternative Hypothese für die Zuordnung des Artefakts stellt den Eberzahn in einen holozänen Kontext, ohne dem Stück dabei eine spezifische Funktion zuzuschreiben. Diese zweite Hypothese war auch darauf gestützt, dass es nur wenige Nachweise von Wildschweinen aus dem Paläolithikum der Schwäbischen Alb gibt. Während der Ausgräber immer die Unsicherheiten in der Ansprache des Artefaktes betonte, akzeptierten einige Kollegeninnen und Kollegen jedoch, dass es sich bei dem Artefakt um eine Frauenstatuette aus dem Magdalénien handelt. Dreizehn Jahre nach der Auffindung haben wir dieses Artefakt neu untersucht und eine Vergleichsstudie durchgeführt. Diese stützt die Hypothese, dass der Wildschweinzahn aus einem holozänen Kontext stammt. Vergleichbare Funde sind aus dem Mesolithikum und Neolithikum Deutschlands, Frankreichs und der Schweiz bekannt; deswegen schlussfolgern wir, dass, obwohl die funktionale Ansprache noch nicht eindeutig ist, es sich um ein Artefakt aus dem Mesolithikum oder Neolithikum handelt. Artefakte aus Wildschweinhauern sind nicht zahlreich und unsere Übersicht über neolithische und mesolithische Wildschweinzahn-Artefakte gibt einen Überblick. Diese Studie erlaubt es uns, die Hypothese, es handle sich um eine Frauenfigurine, zu verneinen, jedoch bereichert das Stück unser Wissen um das holozäne Technologierepertoire in Südwestdeutschland.

Introduction

Scientists and the general public have long been fascinated by figurative artworks of the Paleolithic. Archaeologists as well as the public perceive these items as precious and important for the cultural evolution of humankind. During the 2008 excavation in the backdirt in front of Vogelherd Cave, the team under the direction of the lead author recovered an artifact made from the tusk of a wild boar tooth (Fig. 1). The field report (Conard et al. 2009) described it as an intensively worked lamellae of a boar tooth. The piece measures 7.6 cm in length and has a shape that resembles a stylized Magdalenian female depiction. Interpreting unusual finds like this is not an easy task and requires caution (Conard et al. 2009, 25). Nonetheless, the artifact became part of the permanent exhibition in the Urgeschichtliches Museum Blaubeuren. Here, it is on display in the room “human beings” as part of the art gallery. The hypothesis that this piece is a Magdalenian female depiction is supported in the museum catalog (Kölbl et al. 2021). The aim of this paper is to examine this interpretation of the worked boar tooth and to contextualize it within the Stone Age technocomplexes of the Swabian Jura.

Vogelherd

Vogelherd Cave is located in the Lone Valley near the town of Niederstotzingen. Gustav Riek from the University of Tübingen excavated the site in 1931. He reported archaeological horizons spanning from the Neolithic to the Middle Paleolithic (AH I-IX) (Riek 1932, 1934). Riek’s team completely excavated the site in just three months (Riek 1934; Burkert 1991; Conard and Malina 2006; Schürch et al. 2020, 2022; Schürch and Conard 2022). In his monograph from 1934 Riek presents twelve profiles with a total of nine cultural layers, or archaeological horizons (AH). He assigned AH I to the Neolithic from which the excavators recovered several burials (Orschiedt 1998). Other Neolithic burials come from layers IV and V and were only determined to be Neolithic by direct dating (Conard et al. 2004; Conard 2009). Riek assigned AH II and III to the Magdalenian and designated the underlying AH IV as “upper Aurignacian” and AH V as “middle Aurignacian.” AH VI, which consisted of fine-grain limestone debris and yellow ochre clay was described by Riek as “lower Aurignacian” (Riek 1934, 40-50). Subsequent researchers attributed this layer to the Middle Paleolithic (Conard and Bolus 2003), but the stone artifacts from this layer do not have a clear cultural affiliation. AH VII contains Middle Paleolithic artifacts, which is underlain by Riek’s “Jungacheuléen,” corresponding to AH VIII (Riek 1934; Bosinski 1967). Riek excavated Vogelherd down to the bedrock with AH IX described as the “culture of the cave floor” (Riek 1934). Based on the presence of a molar of a forest elephant from the layer (Lehmann 1954; Niven 2006), AH IX has long been attributed to the last interglacial or MIS 5e. Currently the stratigraphy is being reassessed in the context of B. Schürch’s ongoing doctoral dissertation.

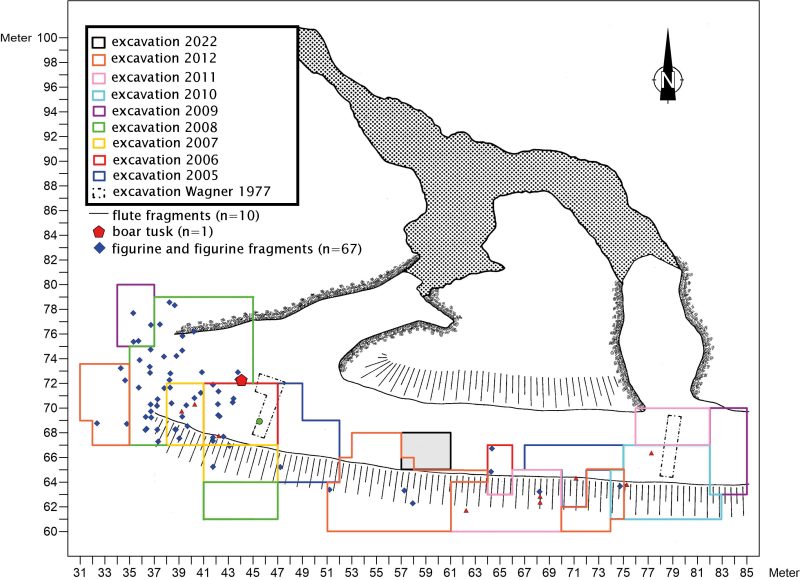

The central focus of this study is the tooth of a boar from Conard’s re-excavations of Riek’s backdirt (Fig. 1). The artifact originates from geological layer HL/KS in square 44/72 and bears the find number 57 (Fig. 2). Excavations in the backdirt ran yearly from 2005 to 2012 and again in 2022 (Conard et al. 2013, 2015, 2016; Conard and Zeidi 2014; Conard 2016). The primary aim of the re-excavation was to recover all classes of archaeological material that Riek’s team overlooked. In keeping with the standards of 1931, the crew had worked with picks and shovels and not conducted screening, let alone waterscreening, which has been shown to greatly improve the recovery of all classes of finds.

The new excavation covers several hundred square meters on the terrace and on the slope in front of to the southwestern and southern entrances to the cave, where Riek’s crew dumped the sediments from the cave. The redeposited sediments maintain a degree of structure, but are clearly mixed to such an extent that the original layers are unrecognizable (Conard and Malina 2006). The sediments in the backdirt are variable but can often be divided as follows: On top lies a humus layer about 10 cm thick, which is called HU. This is followed by a fine, light brown sediment, which is interspersed with much limestone debris, the HL/KS (heller Lehm mit Kalkschutt) layer. This layer corresponds to the main part of the backdirt. It is between 0.5 m and 1.2 m thick (Conard and Zeidi 2011). Beneath the HL/KS lies a dark brown, clayey silt with a high proportion of limestone debris. This is the DKS (dunkler Kalkschutt) deposit, which is about 20 cm thick. The DKS layer lies directly upon the bedrock. The majority of the finds come from the HL/KS deposit, and the other layers yielded far fewer finds. HL/KS corresponds to a relatively homogeneous despite containing a mixture of several layers from the cave. Based on technology and typology, most of the finds can be assigned to the Aurignacian period. This corresponds to the situation described by Riek from his excavation. The sediments in front of the southwest entrance produced more Paleolithic finds than the sediments in front of the south entrance (after Wolf 2015, 232-233; see Schürch et al. 2020, 2021). By 2022, over 95% of the total volume of Riek’s excavation had been reexcavated and waterscreened (Conard and Zeidi 2011; Conard et al. 2016, in press). From the backdirt, we currently know of two microliths that can be assigned to the Mesolithic period.

We also note that Eberhard Wagner of the Heritage Office of the State of Baden-Württemberg conducted a test excavation covering a total of ca. 10 m2 in two areas of Riek’s backdirt. Wagner’s team dug one test trench in front of the southwest entrance and one in front of the south entrance. Remarkably, the publication on this work reports that the team recovered no Paleolithic finds at all (Wagner 1979). Conard’s dig in these areas produced a great wealth of Paleolithic finds. While Wagner’s dig is the only earlier excavation in the backdirt that resulted in a publication, many unauthorized and informal excavations also took place over the years (personal communication F. Seeberger 2005). Of these, the finds recovered by Friedrich Seeberger have received systematic study in connection with his donation of this collection to the Department of Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology of the University of Tübingen. Perhaps the most prominent among the finds from the informal excavations in the backdirt from Vogelherd is a carefully carved head of a lion recovered by Eduard Scheer and now on display as part of the permanent excavations in the State Museum of Württemberg in Stuttgart (Wagner 1981).

Results

On 03.07.2008 Mohsen Zeidi recovered the boar tusk artifact with find number 57 in square meter 44/72 in layer HL/KS just outside the southwest entrance of Vogelherd Cave (Fig. 2). The excavator recognized the find as being exceptional and plotted the artifact as a single find in three dimensions using a Leica total station. The artifact was made from the distal end of a right lower tusk of a wild boar (Fig. 3). The tooth has been split lengthwise and has a curved shape in profile. The artifact is broken at both the proximal and part of the distal end. The preserved distal part carries a strong polish. Both lateral sides of the object are beveled. Researchers who interpreted the find as a female depiction viewed the shape formed by the two beveled surfaces as depicting a human buttock. This surface extends from the sharp ridge of the artifact to the proximal end. The angle changes from the distal end which is inclined 90° toward the labial side to the proximal end with an inclination of about 40° toward the labial side. Various striations are visible on the surface, which suggests that the find was worked with lithic artifacts. On the opposite side of the artifact, another beveled surface is present. This is only preserved at the proximal end with an inclination of approximately 50° to the labial side of the tooth. Here, working traces can be observed as well. From this proximal end to the distal end of the ridge, the bevel changes into a completely rounded edge. This edge is more polished than the rest of the artifact, and the surface is located directly at the transition between the enamel and the dentin.

The microscopic images of the artifact (Fig. 4) show the different worked areas of the edges and surfaces. The tip at the distal end is completely polished. This polish is only absent in places where the artifact is broken (Fig. 4a). At the proximal end, a piece is missing and/or broken (Fig. 4b). Here the double-sided beveling of the artifact can be observed. At the posterior end (Fig. 4c), polish as well as working traces with parallel striations are clearly visible. These parallel lines are visible on the beveled surfaces, except where they were lost to intentional polish or use. These parallel striations run along the posterior edge of the artifact (Fig. 4b, c, d). Here we consider the front side of the artifact to be the main, smooth arching surface (Fig. 1, left), while the back and lateral surfaces bear working traces (Fig. 1, right and Fig. 4).

Most of the front surface is covered by a polish. This polish likely reflects a combination of the natural wear of the tooth and polish from using the tool. Striations are also present here, but, unlike on the posterior lateral edge, they do not underlie the polish, but formed after the polish. These striations are less abundant than on the posterior edge and do not run parallel to the edge, but instead are oriented in an angle to the edge. This suggests that this part of the artifact (Fig. 4e, f) represents the working edge of a tool. Here, the sharp transition from enamel to dentin creates a cutting edge.

Comparative study

To facilitate interpreting the artifact from Vogelherd, we summarize here comparable finds from neighboring regions of Europe. Particularly in the Mesolithic and Neolithic boar tusks represent a material of choice for tools as well as jewelry. In light of the hypothesis that the find represents a female depiction, we also review Magdalenian female figurines from Central Europe.

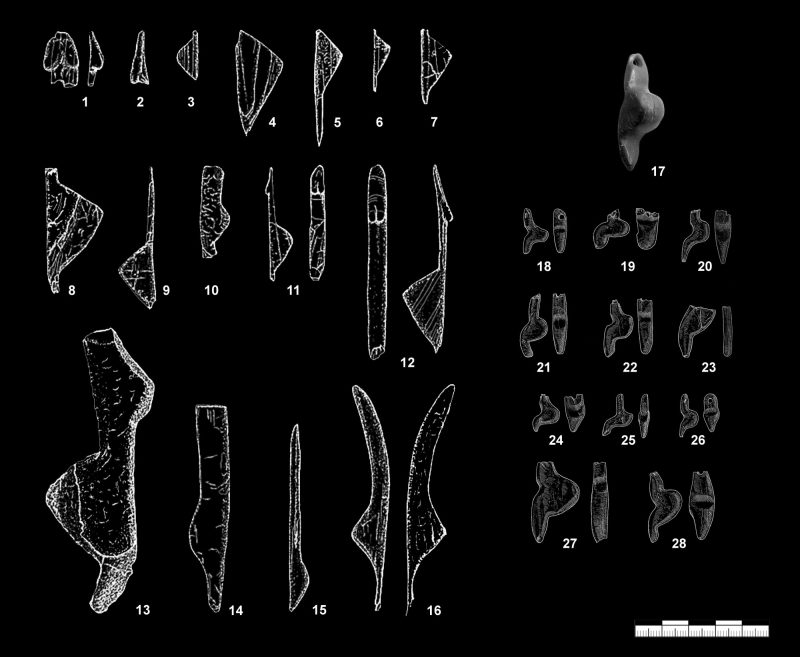

Boar tooth artifacts from the Mesolithic and Neolithic

Finds comparable to the boar tusk artifact from Vogelherd are known from both the Mesolithic and the Neolithic of France, Switzerland and Germany. The best described Mesolithic artifacts come from sites in Switzerland and France (Fig. 5). Some of these artifacts show morphological similarities to the find from Vogelherd. Éva David (2000) has published the chaîne opératoire for these artifacts made from boar tusks from sites including Baume d’Ogens dating to 9950-9530 cal BP (Crotti 2003) and Birsmatten-Basisgrotte dating to 8300 cal BP (Sedlmeier and Pichler 2014). She refers to the morphology of these artifacts as being similar to burins when addressing the function of the artifacts. While examining the ethnological record (Chiquet et al. 1997), she suggests the tools may have served as scrapers or knives.

Other artifacts showing morphological similarities with the artifact from Vogelherd are known from the site Le Cuzoul de Gramat (France) (Marquebielle and Fabre 2021); hearths F1, F2b and F3 of the site are dated to 7700-7000 cal BP (Valdeyron et al. 2014). Here, for the first time, systematic use-wear studies were conducted on these artifacts. Even though this kind of artifact is known from multiple sites (e.g., Péquart et al. 1937; Schuldt 1961; Rozoy 1978), they have never been thoroughly studied. Other examples of similar artifacts come from the sites of Téviec (burials dated to 7500-7200 cal BP; Meiklejohn et al. 2010) and Trou Violet (no direct dates, age estimation 9000-6000 BP; Meiklejohn et al. 2010). Marquebielle and Fabre (2021) describe the objects from Le Cuzoul as “Objects with convex-concave bilateral bevels and spurs: these are diamond-shaped, have a crescent shaped profile, a crescent-shaped cross-section on the proximal part, and a triangular cross-section on the distal part. The first bevel is on the convex edge, while the second one is on the distal end of the opposite edge, and is shorter and more concave. The morphologies and locations of the two bevels create a spur at the distal end of tools…”

The analysis of the use traces showed that the finds were used for scraping (Marquebielle and Fabre 2021). These authors also identified different materials, including hide, bones, wood and other unknown materials that were worked with the boar tusk tools.

In the Neolithic of southern Germany, artifacts made from complete boar canines, typically from male wild boars, or surrounding tooth lamellae, are recorded in faunal assemblages from most periods. These tools use the transition from enamel to dentin to form a working edge, are often curved and pointed, and preserve a working edge transverse to the longitudinal axis of the tooth. These pieces have been described as scrapers for wood and hide processing. The pointed specimens may have been used for scoring and notching (Chiquet et al. 1997, 521; Deschler-Erb et al. 2002, 306). In addition, tooth lamellae or complete teeth with one or more perforations are known from all Neolithic cultures. Excavators have typically interpreted these items as jewelry, for example as decoration of clothing or as necklaces and bracelets. The pieces from the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) bear longitudinal striae on the edges of the boar tusk artifacts which originate from working with flint tools. The Neolithic pieces also frequently show grinding marks running parallel, transverse or obliquely to the longitudinal axis. Such traces cannot be detected on the specimen from the Vogelherd.

For the LBK, there are 27 artifacts made from boar teeth from Herxheim in Rhineland-Palatinate, including three pendants and 24 implements and preforms (Haack 2002, 108-112 and pers. observation). From Hilzingen and Singen in Baden-Württemberg, we know of four artifacts as well as six pieces from sites near the mouth of the Neckar (Fritsch 1998, 219, 239, 240, 249; Sidéra 1998, 89; Lindig 2002, 94/95). Excavations at the Alsatian site of Rosheim yielded three artifacts of this kind, and excavators recovered six additional tools made from boar tusks from Nieder-Mörlen in Hessen (Haack 2002, 108-112; Hüser 2005, 49-50). Considering the large number of LBK sites, this may not seem like much at first glance, but many sites have no preserved organic finds at all. On the basis of the specimens available so far, we conclude that these artifacts made of boar tooth lamellae are standard components of LBK assemblages.

For the Middle Neolithic, and particularly for the Grossgartach cultural group, fieldwork has recovered mainly pierced boar tooth lamellae from graves. Since larger settlements are scarcely known in southern Germany, such finds are not known from domestic contexts. They are, however, documented at the cemeteries of Trebur in Hessen, as well as in Lingolsheim and Erstein in the Alsace (Lichardus-Itten 1980, 53/54, 84/85; Spatz 1999, 146/147). We also identifiedboar tusk artifact from a settlement context of Kraichtal-Gochsheim from Baden-Württemberg (Heide 2001, 154). Excavations have recovered much jewelry made from the lamellae of boar teeth from the beginning of the Late Neolithic in the Schussenried and Hornstaad groups at sites such as Ehrenstein and Hornstaad in Baden-Württemberg, (Paret 1951, 49; Sommer 1997, 210; Heumüller 2009, 66/67, Fig. 15). Sites from the Schwieberding and Schussenried groups with mineral soils like Remseck-Aldingen or Hochdorf and Michelsberg sites like Bruchsal-Aue and Heilbronn-Klingenberg, all from Baden-Württemberg, also produced jewelry and tools made of boar tooth lamellae (Keefer and Joachim 1988, 26/27, 90 Abb. 52,2, 3; Steppan 2003, 75; Keefer 2005, 59, Taf. 29.10; Schlenker 2008, 30/31). In the Early Final Neolithic of the Horgen Culture, artifacts made from boar teeth are common at settlements on Lake Constance and Lake Zurich. Examples include items from the Swiss sites of Arbon Bleiche III and Zurich Parkhaus Opéra (Deschler-Erb et al. 2002, 304-307; Jochum Zimmermann 2016, 176-177). Fishhooks made from boar tooth lamellae represent a special form, for which the manufacturing process has been described in detail (Deschler-Erb et al. 2002, 307-309). Additionally, excavations at Stuttgart-Stammheim Neubaugebiet-Süd led to the recovery of a small boar tooth knife from the Horgen-period (Matuschik and Schlichtherle 2009, 56).

In the Schnurkeramik period, pierced boar teeth and boar tooth lamellae often count among the grave goods (Dresely 2004, 147). In southern Germany, however, they are rare during this time, but two examples have recovered from Grave 16 in the cemetery of Tauberbischofsheim-Impfingen in Baden-Württemberg (Dresely 2004, 67).

The Magdalenian female figurines of Central Europe

Aside from the important fact that boar are classic interglacial animals in southern Germany that are absent from undisturbed Magdalenian assemblages, at first glance, the piece from Vogelherd could be thought to be a Magdalenian female figure based on its shape (Kölbl et al. 2021). Another curious find is a bone from the neighboring site of Hohlenstein-Stadel in the Lone Valley that Eberhard Wagner interpreted as a female figurine (Wagner 1984). Here we briefly consider the background for why such finds could be misinterpreted to be Magdalenian artworks.

The well-known Magdalenian open-air sites of Gönnersdorf and Andernach in the Neuwied Basin of the Central Rhine Valley have yielded many unambiguous schematized female figurines, both carved and engraved (Bosinski and Fischer 1974; Höck 1993; Bosinski 2008, 2011) (Fig. 6.2-16). Hermann Schaaffhausen (1888) led the first archaeological excavation in Andernach in 1883 and recovered small pieces of slate bearing intentional scratches. None of these, however, show unambiguously female representations. Gerhard Bosinski’s impressive excavation at Gönnersdorf led to the discovery of numerous examples of figurines and engravings of stylized female depictions. These depictions follow the same pattern, where the emphasis is on the side view of the figurines. To date, none of these female representations has a head. Typically, their upper body is elongated and thin, and a pronounced triangular part represents the buttocks. The legs are represented by a simple stick-like form, without feet. Sometimes breasts are carved or engraved in the upper part of the body; now and then arms and very rarely hands are indicated on engravings. These characteristics define the Gönnersdorf type of Magdalenian schematic female figures, which have a broad geographic distribution and help to define this facies of the Magdalenian (Bosinski 2011). Such depictions were known earlier, for example, an engraving on limestone from Hohlenstein (Bavaria), found in 1914 (see Kühn 1965, 225), but Bosinski was the first archaeologist to define a specific type for these stylized figurines.

Engraved schematic female representations frequently occur on slate plates or on limestone. In Gönnersdorf alone, excavators recovered 267 engravings depicting stylized females (Bosinski and Fischer 1974; Bosinski 1982, 2011). They range from a single person to a small group of women. One of the best-known depictions seem to show groups of women dancing, including a woman with a baby in a bundle strapped on her back. In many publications Bosinski (2008) has described the images as young women with their arms raised, knees bent and buttocks pushed back. Ten statuettes and fragments of statuettes made from ivory and three made from antler have also been recovered from Gönnersdorf. In addition to these, the inhabitants of Gönnersdorf carved five figurines from Devonian slate. At Andernach, opposite Gönnerdorf on the western side of the Rhine, Magdalenian people carved one bone statuette and eighteen small female figurines from ivory, as well as one particularly large ivory statuette (ca. 21 cm; Höck 1993; Bosinski 2008). Many of the finds are preserved in fragmentary condition. Engraved representations augment the assemblage of female figures from Andernach.

The same style of female figurine is known from two sites in eastern Germany, at Nebra, near the city of Halle (Toepfer 1965; Mania 1999, 2004), and Oelknitz, near the city of Jena (Neumann 1933a, b; Bosinski 1982, 44). The Magdalenian artifacts date to ca. 15,000 years cal BP. Here, hunter-gatherers carved figurines from ivory, bone and river cobbles. Nebra yielded three ivory statuettes and a bone figurine. Dietrich Mania (2004) also counts a statuette, which was destroyed during excavations in the 1960s. A complete female figure of the Gönnersdorf type and a fragment corresponding to the buttocks of this female depiction are known from Oelknitz. In addition, excavators recovered five small pebbles that had been shaped into schematic female figurines (Bosinski 1982). One figurine of this type is also known from the site of Garsitz in Thüringen (Feustel 1989; see Höck 1993).

At Petersfels Cave, near Engen in southwestern Germany (Peters 1930), and at Neuchâtel-Monruz in Switzerland (Egloff 1990), Magdalenian carvers fashioned similar schematic female figures from jet (Fig. 6.17-28). These statuettes often bear a perforation at the upper end and are typically described as pendants. The Magdalenian settlement of Monruz yielded three female statuettes of this kind (12.5, 13.7 and 16.5 mm long). Petersfels is rich in female statuettes, with a minimum of 12 figurines of the Gönnersdorf type made from jet. Additional preforms for the carving of these specific figurines derive from the site (e.g., Mauser 1970, plate 96) as well as engravings on a small piece of ivory which could be interpreted as stylized women in a row (Mauser 1970, 71-72). In addition, three other female figurines from Petersfels were carved from antler (Peters 1930; Bosinski 1982). Sebastian Pfeifer (2017) identified one of these antler artifacts as a preform for a perforated baton. One of the two other items, however, does not have the typical shape of a figurine of the Gönnersdorf type.

With this information in mind we re-examine the find from Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave (Fig. 7) that Wagner interpreted as a female statuette (Wagner 1984, 1985). According to Wagner, this artifact does not have a secure stratigraphic context but was found under a mixed layer near the surface of the site. It consists of three pieces that he glued together. He describes the find as being made from ivory. It measures 4.7 cm in length. Wagner highlights nine fine holes on the surface as a special feature and describes the piece as being a female depiction of the Gönnersdorf type. The object is part of the inventory of the Landesmuseum Württemberg in Stuttgart.

We investigated this item microscopically using a Hirox-HRX-01 3D digital microscope Hirox HRX-01 and an Olympus SZX 7 digital stereomicroscope. We were unable to detect any traces of anthropogenic modification. The piece shows the typical structure of bone, with fine openings over the surface. No spongeous bone is visible, so we are dealing with a piece of compact bone with a minimum diameter of 1.2 cm. Wagner describes “nine holes” (Fig. 7b) on the surface of the find (Wagner 1985). These holes, however, are Harvers channels (Harvers 1699) and are not of anthropogenic origin. They are situated in the center of an osteon, the basic structural unit of a compact bone. These channels represent natural openings for blood or nerves. The whole surface of Wagner’s find is irregular (Fig. 7a), in contrast to the surface of ivory, which is regular and does not show pores at all (Locke 2008; Heckel 2018). With the help of a microscope an observer sees that the holes are natural features. The diameter of the holes we measured range from 0.28 mm to 1.03 mm. The overall rounded surface of the piece is the result of taphonomic processes rather than human agency. We conclude that this find is a piece of unworked bone rather than a female depiction.

Two additional objects from western Germany have been interpreted as Magdalenian female depictions. Elisabeth Schmid (1972/73) describes the first find, which was recovered from the surface of the field “Auf der Sandkaul” in 1939, as a female figurine carved from agate. The object is a stone tool with the possible shape of a Gönnersdorf female depiction. The second item is also a surface find that was collected by the amateur archaeologist Adolf Regen in the winter of 2015/2016 at the site of Waldstetten in Baden-Württemberg (Regen et al. 2019). Harald Floss (2021) interprets this quartzite pebble with incisions at one end as an anthropomorphic depiction of the type Gönnersdorf showing both female and male characteristics. Because of the unstratified context of both of these finds, they cannot be designated Magdalenian female figurines with a high degree of certainty.

Further east, the site of Wilczyce in Poland produced one figurine made from bone, one figurine made from ivory and eight figurines made from flint. All figurines are of the Gönnersdorf type (Boroń et al. 2012). From the sites Býči Skála in the Czech Republic, excavators recovered one decorated pebble that resembles a schematic female depiction (Valoch 1978). The Pekarna Cave nearby yielded a figurine of Gönnersdorf type made from ivory (Absolon and Czižek 1932).

During the Magdalenian and Eastern Epigravettian stylized representations of females were part of the daily life and are known in considerable numbers. They are cultural markers of the Magdalenian within many archaeological assemblages (e.g., Bosinski 2011). Engravings of this type are only known during the Magdalenian of west-central Europe, while sculptures are characteristic for Central and Eastern Europe (Khlopachev et al. 2018). For the sculptures, mammoth ivory, antler, jet and sometimes stones of different kinds represent the preferred raw materials. So far, no Magdalenian female depictions of Gönnersdorf type are known made from animal teeth, and boars are absent from unmixed Magdalenian faunal assemblages of Central Europe. In the Late Paleolithic site of Niederbieber, an arrow-shaft smoother made from sandstone was excavated in 1981 (Loftus 1982; Bosinski 2008; Gelhausen 2009). Stylized female figures of the Gönnersdorf type are engraved in rows on this piece. This shows the continuity of these specific representations until the end of the last Ice Age. From the Mesolithic such representations are not known. The information summarized above provides a basis for a clear interpretation of the boar tusk artifact found in 2008 at Vogelherd.

Conclusion

In general, we recommend avoiding hasty interpretations of artifacts as artworks without a detailed analysis to support these claims. The history of research is filled with bold claims of spectacular finds that have turned out to be false, and the burden of proof lies with the researchers making such statements. The artifact made from a boar tusk from Vogelherd is a unique find for the site, and it originates from mixed deposits of Late Pleistocene and Holocene age. To date, boar is absent from intact Magdalenian faunal assemblages from southwestern Germany. At present no evidence for the use of boar teeth from the Pleistocene of southern Germany is known, and we are unaware of other Magdalenian female depictions made of boar tusks. Thus, except for the general shape of the artifact, there is no convincing evidence justifying the interpretation the artifact as a female depiction.

Starting in the Mesolithic and continuing in the Neolithic, boar tusks are well documented from archaeological contexts in southwestern Germany and neighboring regions. Artifacts from the Mesolithic and Neolithic of France, Switzerland and southern Germany show strong similarities to the find from Vogelherd, and they show nearly identical modifications. Preliminary functional studies suggest that these artifacts may have been used for scraping activities, as is indicated by associated use-wear. However, research is needed to determine more precisely what function these artifacts served. A wide variety of objects made from boar teeth have also been described from the Neolithic of southwestern Germany. Tools from this material tend to use the transition between enamel and dentin as a working edge, just as we have described for the Vogelherd artifact. Additionally, boar tusks often served as raw material for jewelry.

In our view, the available evidence clearly refutes the hypothesis that the boar tusk artifact from Vogelherd represents a Magdalenian female figurine. The find is likely a tool from the Mesolithic or the Neolithic. We recommend exercising considerable caution before rushing to interpret ambiguous find from unclear cultural stratigraphic context as works of Paleolithic art. In such cases overwhelming evidence is needed before such claims should be accepted by the scientific community.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Michael Bolus for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

Absolon, K. and Czižek, R. 1932: Paleolitický výzkum jeskyně Pekárny na Moravě. Třetí předběžná zpráva za rok 1927 [Zusammenfassung: Die palaeolithische Erforschung der Pekárna-Höhle in Mähren. Dritte, vorläufige Mitteilung für das Jahr 1927]. Časopis Moravského Muzea/Acta Musei Moraviae 26-27, 479–598.

Boroń, T., Królik, H., and Kowalski, T. 2012: Les figurines féminines magdaléniennes du site de Wilczyce 10 (district de Sandormierz, Pologne). In: J. Clottes (ed.), L’art pléistocène dans le monde. Actes du Congrès IFRAO, Tarasconsur-Ariège, septembre 2010. Symposium «Art mobilier pléistocène». Tarascon-sur-Ariège: Société préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées, CD-1379–CD-1391.

Bosinski, G. 1967: Die mittelpaläolithischen Funde im westlichen Mitteleuropa. Fundamenta A4. Köln/Graz: Böhlau Verlag.

Bosinski, G. 1982: Die Kunst der Eiszeit in Deutschland und in der Schweiz. Kataloge vor- und frühgeschichtlicher Altertümer 20. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag.

Bosinski, G. 2008: Urgeschichte am Rhein. Tübinger Monographien zur Urgeschichte. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.

Bosinski, G. 2011: Femmes sans tête. Une icône culturelle dans l’Europe de la fin de l’époque glaciare. With contributions by E. Brunel, J.-M. Chauvet, and R. Pigeaud. Paris: éditions errance.

Bosinski, G. and Fischer, G. 1974: Die Menschendarstellungen von Gönnersdorf der Ausgrabung von 1968. Der Magdalénien-Fundplatz Gönnersdorf Bd. 1. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag.

Burkert, W. 1991: Stratigraphie und Rohmaterialnutzung im Vogelherd. Unpublished master thesis, University of Tübingen.

Chiquet, P., Rachez, É., and Pétrequin, P. 1997: Les défenses de sanglier. In: P. Pétrequin (ed.), Les Sites littoraux néolithiques de Clairvaux-les-Lacs et de Chalain (Jura). Vol. III: Chalain station 3, 3200-2900 av. J.-C., Vol. 2. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 511–521.

Conard, N. J. 2009: Jünger als gedacht! Zur Neudatierung der Menschenreste vom Vogelherd. In: Archäologisches Landesmuseum Baden-Württemberg/Abteilung Ältere Urgeschichte und Quartärökologie der Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen (eds.), Eiszeit. Kunst und Kultur. Begleitband zur Großen Landesausstellung Eiszeit – Kunst und Kultur im Kunstgebäude Stuttgart. Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, 116.

Conard, N. J. 2016: Tonnenweise Funde aus dem Abraum – neue Grabungen im Vogelherd. Archäologie in Deutschland 6/2016, 26–27.

Conard, N. J. and Bolus, M. 2003: Radiocarbon dating the appearance of modern humans and timing of cultural innovations in Europe: new results and new challenges. Journal of Human Evolution 44, 331–371.

Conard, N. J. and Malina, M. 2006: Schmuck und vielleicht auch Musik am Vogelherd bei Niederstotzingen-Stetten ob Lonetal, Kreis Heidenheim. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Würrtemberg 2005, 21–25.

Conard, N. J. and Zeidi, M. 2011: Der Fortgang der Ausgrabungen am Vogelherd. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2010, 61–64.

Conard, N. J. and Zeidi, M. 2014: Ausgrabungen in der Fetzershaldenhöhle und der Lindenhöhle im Lonetal sowie neue Funde aus dem Vogelherd. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2013, 63–67.

Conard, N. J., Grootes, P. M., and Smith, F. H. 2004: Unexpectedly recent dates for human remains from Vogelherd. Nature 430, 198–201.

Conard, N. J., Malina, M., and Verrept, T. 2009: Weitere Belege für eiszeitliche Kunst und Musik aus den Nachgrabungen 2008 am Vogelherd bei Niederstotzingen-Stetten ob Lonetal, Kreis Heidenheim. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2008, 23–26.

Conard, N. J., Zeidi, M., and Bega, J. 2013: Die letzte Kampagne der Nachgrabungen am Vogelherd. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2012, 84–88.

Conard, N. J., Janas, A., and Zeidi, M. 2015: Neues aus dem Lonetal: Ergebnisse von Ausgrabungen an der Fetzershaldenhöhle und dem Vogelherd. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2014, 59–64.

Conard, N. J., Zeidi, M., and Janas, A. 2016: Abschließender Bericht über die Nachgrabung am Vogelherd und die Sondage in der Wolftalhöhle. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2015, 66–72.

Conard, N. J., Zeidi, M., and Janas, A. 2023: Neue Ausgrabungen am Vogelherd im Lonetal. Archäologische Ausgrabungen in Baden-Württemberg 2022, 59–61.

Crotti, P. 2003: Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in western Switzerland: economy and mobility. Preistoria Alpina 39, 155–163.

David, É. 2000: L’industrie en matières dures animales des sites mésolithiques de la Baume d’Ogens et de Birsmatten-Basisgrotte (Suisse). Résultats de l’étude technologique et comparaisons. In: P. Crotti (ed.), Epipaléolithique et Mésolithique. Actes de la Table ronde, Lausanne 21-23 novembre 1997. Cahiers d’archéologie romande 81. Lausanne: Musée cantonal d’archéologie et d’histoire, 79–100.

Deschler-Erb, S., Marti-Grädel, E., and Schibler, S. 2002: Die Knochen-, Zahn- und Geweihartefakte. In: A. De Capitani, S. Deschler-Erb, U. Leuzinger, E. Marti-Grädel, and J. Schibler, Die jungsteinzeitliche Seeufersiedlung Arbon-Bleiche 3. Funde. Archäologie im Thurgau 11. Frauenfeld: Amt für Archäologie des Kantons Thurgau, 277–366.

Dresely, V. 2004: Schnurkeramik und Schnurkeramiker im Taubertal. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 81. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

Egloff, M. 1990: La dame de Monruz. Analyse d’une démarche archéologique. In: Rénovations archéologiques/Archäologie im Umbau. Catalogue d’exposition au Musée Schwab. Genève : Musée Schwab/P.I.A., 49–56.

Feustel, R. 1989: Garsitz. In: J. Hermann (ed.), Archäologie in der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik. Denkmale und Funde. Two volumes. Leipzig/Jena/Berlin: Urania Verlag, 386–388.

Floss, H. 2021: Die Venus von Waldstetten und das Paläolithikum im Ostalbkreis. Reihe Heimatbücher der Gemeinde Waldstetten. Schwäbisch Gmünd.

Fritsch, B. 1998: Die linearbandkeramische Siedlung Hilzingen „Forsterbahnried“ und die altneolithische Besiedlung des Hegaus. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Gelhausen, F. 2009: Die Fundkonzentrationen der Fläche II des allerødzeitlichen Fundplatzes Niederbieber, Stadt Neuwied (Rheinland-Pfalz). Jahrbuch des Römisch Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 56, 1–38.

Haack, F. 2002: Die bandkeramischen Knochen-, Geweih- und Zahnartefakte aus den Siedlungen Herxheim (Rheinland-Pfalz) und Rosheim (Alsace). Unpublished master thesis, University of Freiburg i.Br.

Harvers, C. 1699: A short Discourse concerning Concoction: Read at a Meeting of the Royal Society, May 1699. Philosophical Transactions 21, 233–247.

Heckel, C. 2018. Qu’est-ce que l’Ivoire?/What is Ivory? L’Anthropologie 122, 306–315.

Heide, B. 2001: Das ältere Neolithikum im westlichen Kraichgau. Internationale Archäologie 53. Rahden/Westf.: Verlag Marie Leidorf.

Heumüller, M. 2009: Der Schmuck der jungneolithische Seeufersiedlung Hornstaad-Hörnle IA im Rahmen des mitteleuropäischen Mittel- und Jungneolithikums. Siedlungsarchäologie im Alpenvorland X. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 112. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

Höck, C. 1993: Die Frauenstatuetten des Magdalenien von Gönnersdorf und Andernach. Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 40, 253-316.

Hüser, A. 2005: Die Knochen- und Geweihartefakte der linearbandkeramischen Siedlung Bad Nauheim-Nieder-Mörlen in der Wetterau. Kleine Schriften aus dem Vorgeschichtlichen Seminar Marburg 55. Marburg: Vorgeschichtliches Seminar der Philipps-Universität.

Jochum Zimmermann, E. 2016: Knochen- und Hirschgeweihartefakte. In: C. Harb and N. Bleicher (eds.), Zürich-Parkhaus Opéra. Eine neolithische Feuchtbodenfundstelle, Band 2: Funde. Monographien der Kantonsarchäologie Zürich 49. Zürich und Egg: Amt für Raumentwicklung, Archäologie und Denkmalpflege, 166–187.

Keefer, E. 2005: Hochdorf II. Eine jungsteinzeitliche Siedlung der Schussenrieder Kultur. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 27. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

Keefer, E. and Joachim, W. 1988: Eine Siedlung der Schwieberdinger Gruppe in Aldingen, Gde. Remseck am Neckar, Kreis Ludwigsburg. With contributions by J. Biel and M. Kokabi. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 13, 1–114.

Khlopachev, G., Vercoutère, C., and Wolf, S. 2018: Les statuettes féminines en ivoire des faciès gravettiens et post-gravettiens en Europe centrale et orientale: modes de fabrication et de representation. L’Anthropologie 122, 492–521.

Kölbl, S., Conard, N. J., and Hiller, G. 2021: Where Humans Came to be. Accompanying book to the exhibition. Blaubeuren: Urgeschichtliches Museum Blaubeuren.

Kühn, H. 1965: Eiszeitkunst. Die Geschichte ihrer Erforschung. Göttingen/Berlin/Frankfurt/Zürich: Musterschmidt Verlag.

Lehmann, U. 1954: Die Fauna des „Vogelherds“ bei Stetten ob Lonetal (Württemberg). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie 99, 33–146.

Lichardus-Itten, M. 1980: Die Gräberfelder der Großgartacher-Gruppe im Elsass. Saarbrücker Beiträge zur Altertumskunde 25. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag.

Lindig, S. 2002: Das Früh- und Mittelneolithikum im Neckarmündungsgebiet. Universitätsschriften zur Prähistorischen Archäologie 85. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag.

Locke, M. 2008: Structure of Ivory. Journal of Morphology 269, 423-450.

Loftus, J. 1982: Ein verzierter Pfeilschaftglätter von Fläche 64/74-73/78 des spätpaläolithischen Fundplatzes Niederbieber/Neuwieder Becken. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 12, 313–316.

Mania, D. 1999: Nebra – eine jungpaläolitische Freilandstation im Saale-Unstrut-Gebiet. With contributions by V. Toepfer and E. Vlček. Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archäologie – Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Sachsen-Anhalt 54. Halle (Saale): Landesamt für Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt.

Mania, D. 2004: Jäger und Sammler vor 15 000 Jahren im Unstruttal. In: H. Meller (ed.), Paläolithikum und Mesolithikum. Kataloge zur Dauerausstellung im Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle, Band 1. Halle (Saale): Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt/Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte, 233–249.

Marquebielle, B. and Fabre, E. 2021: Tools made from wild boar canines during the French Mesolithic: A technological and functional study of the collection from Le Cuzoul de Gramat (France). In: D. Borić; D. Antonović, and B. Mihailović (eds.), Foraging Assemblages, vol 2. Belgrade & New York: Serbian Archaeological Society/The Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America, Columbia University, 526–534.

Matuschik, I. and Schlichtherle, H. 2009: Zeitgenossen des Gletschermannes am Mittleren Neckar. Die Siedlungen Stuttgart-Stammheim und -Mühlhausen. Archäologische Informationen aus Baden-Württemberg 56. Esslingen: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege im Regierungsbezirk Stuttgart.

Mauser, P. F. 1970: Die jungpaläolithische Höhlenstation Petersfels im Hegau (Gemarkung Bittelbrunn, Ldkrs. Konstanz). With a contribution by K. Gerhardt. Badische Fundberichte, Sonderheft 13. Freiburg: Otto Kehrer KG.

Meiklejohn, C., Bosset, G. and Valentin, F. 2010: Radiocarbon dating of Mesolithic human remains in France. Mesolithic Miscellany 21(1), 10–57.

Neumann, G. 1933a: Leben und Treiben vor 20.000 Jahren. Thüringer Fähnlein 2, 321–331.

Neumann, G. 1933b: Eine Freilandsiedlung des Hochmagdalénien. Beiträge zur Geologie von Thüringen 3, 362–364.

Niven, L. 2006: The Palaeolithic Occupation of Vogelherd Cave. Implications for the Subsistence Behavior of Late Neanderthals and Early Modern Humans. Tübingen Publications in Prehistory. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.

Orschiedt, J. 1998: Eine neolithische Sekundärbestattung aus dem Vogelherd bei Stetten, Gem. Niederstotzingen, Kr. Heidenheim. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 22 (1), 161–172.

Paret, O. 1951: Das Steinzeitdorf Ehrenstein bei Ulm (Donau). Stuttgart: E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele u. Obermiller).

Péquart, M., Péquart, S.-J., Boule, M., and Valois, H. 1937: Téviec: station-nécropole mésolithique du Morbihan. Archives de l’Institut de paléontologie humaine, Mémoire 18. Paris: Masson.

Peters, E. 1930: Die altsteinzeitliche Kulturstätte Petersfels. Augsburg: Verlag Dr. Benno Filser.

Pfeifer, S. J. 2017: Die Geweihfunde der magdalénienzeitlichen Station Petersfels. Eine archäologisch-taphonomische Studie. Forschungen und Berichte zur Archäologie in Baden-Württemberg 3. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag.

Regen, A., Naak, W., Wettengl, S., Fröhle, S., and Floss, H. 2019: Eine Frauenfigur vom Typ Gönnersdorf aus der Magdalénien-Freilandstelle Waldstetten-Schlatt, Ostalbkreis, Baden-Württemberg. In: H. Floss (ed.), Das Magdalénien im Südwesten Deutschlands, im Elsass und in der Schweiz. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag, 267–276.

Riek, G. 1932: Paläolithische Station mit Tierplastiken und menschlichen Skelettresten bei Stetten ob Lontal. Germania 16, 1–8.

Riek, G. 1934: Die Eiszeitjägerstation am Vogelherd im Lonetal I: Die Kulturen. Tübingen: Akademische Buchhandlung Franz F. Heine.

Rozoy, J.-G. 1978: Les Derniers Chasseurs. L’Epipaléolithique en France et en Belgique. Three volumes. Bulletin de la société archéologique champenoise, numéro spécial. Charleville.

Schaaffhausen, H. 1888: Die vorgeschichtliche Ansiedelung in Andernach. Bonner Jahrbücher 86, 1–41.

Schlenker, B. 2008: Die Knochen- und Geweihartefakte aus dem jungneolithischen Erdwerk von Heilbronn-Klingenberg. Ein Beitrag zur Funktionsanalyse prähistorischer Gerätfunde. In: B. Schlenker, E. Stephan, and J. Wahl, Michelsberger Erdwerke im Raum Heilbronn, Band 3: Osteologische Beiträge. Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Baden-Württemberg 81/3. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 9–130.

Schmid, E. 1972/73: Eine jungpaläolithische Frauenfigur aus Achat von Weiler bei Bingen. Quartär 23/24, 175–180.

Schuldt, E. 1961: Hohen Viecheln. Ein mittelsteinzeitlicher Wohnplatz in Mecklenburg. With contributions by O. Gehl, H. Schmitz, E. Soergel, and H. H. Wundsch. Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, Schriften der Sektion für Vor und Frühgeschichte 10. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, Berlin.

Schürch, B. and Conard, N. J. 2022: Reassessing the cultural stratigraphy of Vogelherd Cave and the settlement history of the Lone Valley of SW Germany. Poster at the 12th Annual Meeting of the European Society for the Study of Human Evolution, Tübingen 22-24 September 2022. Abstract: PaleoAnthropology 2022(2), 578.

Schürch, B., Wolf, S., Schmidt, P., and Conard, N. J. 2020: Mollusken der Gattung Glycymeris aus der Vogelherd-Höhle bei Niederstotzingen (Lonetal, Südwestdeutschland). Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 29, 53–79.

Schürch, B., Venditti, F., Wolf, S., and Conard, N. J. 2021: Glycymeris molluscs in the context of the Upper Palaeolithic of Southwestern Germany. Quartär 68, 131–156.

Schürch, B., Wettengl, S., Fröhle, S., Conard, N., and Schmidt, P. 2022: The origin of chert in the Aurignacian of Vogelherd Cave investigated by infrared spectroscopy. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0272988.

Sedlmeier, J. and Pichler, S. 2014: Nenzlingen, Birsmatten-Basisgrotte: Alte Bestattung – Neue Erkenntnisse. Archäologie Basselland, Jahresbericht 2013, 159–161.

Sidéra, I. 1998: Die Knochen-, Geweih- und Zahnartefakte aus Vaihingen. Ein Überblick. In: R. Krause, Die bandkeramischen Siedlungsgrabungen bei Vaihingen an der Enz, Kreis Ludwigsburg (Baden-Württemberg). Ein Vorbericht zu den Ausgrabungen von 1994-1997. Bericht der Römisch-Germanischen Kommission 79, 81–90.

Sommer, U. 1997: Die Kleinfunde von Ehrenstein. In: J. Lüning, U. Sommer, K. A. Achilles, H. Krumm, J. Waiblinger, J. Hahn, and E. Wagner, Das jungsteinzeitliche Dorf Ehrenstein (Gemeinde Blaustein, Alb-Donau-Kreis). Ausgrabung 1960. Teil III: Die Funde. Forschungen und Berichte zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Baden-Württemberg 58. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 181–237.

Spatz, H. 1999: Das mittelneolithische Gräberfeld von Trebur, Kreis Groß-Gerau. Two volumes. Materialien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte von Hessen 19. Wiesbaden: Selbstverlag des Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege Hessen.

Steppan, K. 2003: Taphonomie – Zoologie – Chronologie – Technologie – Ökonomie. Die Säugetierreste aus den jungsteinzeitlichen Grabenwerken in Bruchsal/Landkreis Karlsruhe. Materialhefte zur Archäologie in Baden-Württemberg 66. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag.

Toepfer, V. 1965: Drei spätpaläolithische Frauenstatuetten aus dem Unstruttal bei Nebra. Fundberichte aus Schwaben N. F. 17 (Festschrift für G. Riek), 103-111.

Valdeyron, N., Henry, A., Marquebielle, B., Bosc-Zanardo, B., Gassin, B., Michel, S., and Philibert, S. 2014: Le Cuzoul De Gramat (Lot, France): A key sequence for the early Holocene in southwest France. In: F. W. F. Foulds, H. C. Drinkall, A. R. Perri, D. T. G. Clinnick, and J. W. P. Walker (eds.), Wild Things. Recent Advances in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 94–105.

Valoch, K. 1978: Eine gravierte Frauenstatuette aus der Býčí Skála-Höhle in Mähren. Anthropologie 16, 31–33.

Wagner, E. 1979: Untersuchungen an der Vogelherdhöhle im Lonetal bei Niederstotzingen, Kreis Heidenheim. Archäologische Ausgrabungen 1978. Bodendenkmalpflege in den Reg.-Bez. Stuttgart und Tübingen, 7–10.

Wagner, E. 1981: Eine Löwenkopfplastik aus Elfenbein von der Vogelherdhöhle. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 6, 29–58.

Wagner, E. 1984: Eine Frauenstatuette aus Elfenbein vom Hohlenstein-Stadel im Lonetal, Gemeinde Asselfingen, Alb-Donau-Kreis. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt 14, 357–360.

Wagner, E. 1985: Fundschau – Altsteinzeit: Asselfingen. Fundberichte aus Baden-Württemberg 10, 453–454.

Wolf, S. 2015: Schmuckstücke. Die Elfenbeinbearbeitung im Schwäbischen Aurignacien. Tübinger Monographien zur Urgeschichte. Tübingen: Kerns Verlag.