Zusammenfassung

Dieser Beitrag untersucht das technologische und allgemeine Erscheinungsbild der mittelpaläolithischen Inventare aus mehreren Fundstellen im Gebiet der Côte Chalonnaise, Burgund, Frankreich. Ausgehend von mehreren charakteristischen Merkmalen innerhalb des stratifizierten Materials der Grotte de la Verpillière II (Germolles), konnten die aktuellen Forschungen kongruente technologische Muster für eine Reihe der umliegenden Fundstellen nachweisen.

Die wichtigsten gemeinsamen Merkmale sind das Vorhandensein von Keilmessern, mit und ohne Schneidenschlag, sowie einheitliche Produktionsstrategien, die auf dem Levallois-Konzept basieren.

Damit liefert die vorliegende Arbeit erste Anhaltspunkte für ein zusammenhängendes Fundstellencluster in der Region. Erste Datierungsergebnisse deuten auf einen chronologischen Kontext im späten Mittelpaläolithikum hin.

Die räumliche Verteilung der Fundstellen und die Zusammensetzung der jeweiligen Inventare erlaubt es, eine erste Hypothese zur funktionalen Organisation zwischen den Fundstellen aufzustellen. Darüber hinaus liefern kürzlich durchgeführte Feldforschungen und anschließende Analysen Belege für eine fundplatzspezifische Organisation, die den mikroregionalen Überblick über das späte Mittelpaläolithikum im Zusammenspiel von Technologie, Chronologie und Räumlichkeit vervollständigen.

Introduction

Southern Burgundy has a long history of Paleolithic research, starting at the very beginning of archaeological research itself in the 1860s with sites such as Grotte de la Verpillière I, Grotte de la Mère Grand or Solutré (e.g., Combier 1959; Ferry and Arcelin 1868; Méray 1869, 1876; Mortillet 1883). Over the decades, the region has also revealed a very dense Paleolithic occupation record, especially for Middle Paleolithic sites (Fig. 1) which constitute 42% of the known Paleolithic sites (Pautrat 2016). This is true for the wider Saône-et-Loire Department as well as for the Côte Chalonnaise (Fig. 1).

The topography of the region, featuring narrow corridors between the Jurassic cliffs (Burgundian cuesta) that allow passage from the Saône Valley in the east to the elevated hinterland in the west, might be one reason for the dense occupation of the Côte Chalonnaise (Herkert et al. 2015; Hoyer et al. 2014a). Furthermore, there is abundant lithic raw material available in close proximity to the sites (Fig. 1). The dominant siliceous material is flint from the argiles à silex (FAS; clays-with-flint), which varies greatly in quality, and various varieties of Jurassic chert (chaille bathonienne and chaille bajocienne, CB), which are generally more coarse-grained than the flint. Quartz, quartzite and granite are also available in primary positions, as gravels on terraces or in riverbeds (Floss 2005b; Herkert et al. 2015, 2016b; Siegeris 2014, 2020; Siegeris and Floss 2015).

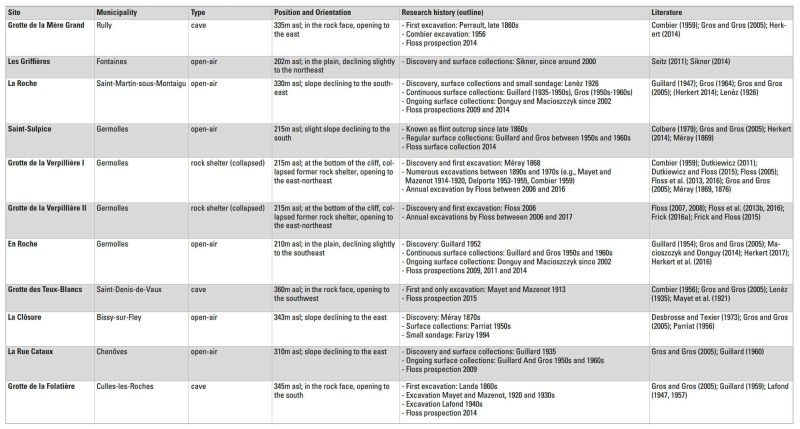

Starting with the recent fieldwork carried out at Grotte de la Verpillière I and II in 2006 (Floss 2007, 2008, 2009a, 2009c; Floss et al. 2013a, 2013b, 2014, 2016, 2017; Frick 2014b, 2017; Frick and Steigerwald 2016a, 2016b; Hoyer et al. 2014b), research has been expanded to include a multitude of other sites in the region; these consist of cave sites, rockshelters and open-air sites (Table 1 and Fig. 1).

All of the sites have yielded lithic artifacts attributable to the Middle Paleolithic, but the assemblages derive either from older excavations or from surface collections. In order to widen the focus, and to enable comparative studies, the various collections have been re-examined (Dutkiewicz 2011; Frick 2010; Herkert 2016, 2017; Herkert et al. 2016a, 2015; Macioszczyk and Donguy 2014; Sikner 2014) and some of this work is still ongoing (see Herkert and Frick 2020). Over the course of more than 150 years of research, which has been primarily based on typological criteria, the various assemblages in question have been interpreted quite differently and thus have been attributed to various classic Middle Paleolithic techno-complexes or facies (cf. Frick 2014a; Herkert and Frick 2020). To cite but a few examples, the material from Grotte de la Mère Grand in Rully has been identified as Micoquien final (Combier and Ayroles 1976), La Roche at Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu as Moustérien type Quina (Combier and Ayroles 1976) or as Moustérien groupe Quina rhodanien (Pouliquen 1983), and Saint Sulpice at Germolles as Moustérien typique de faciès levalloisien (Colbère 1979). The assemblage from Grotte de la Verpillière I has been ascribed to a Moustérien de tradition acheulénne (Combier and Ayroles 1976; Desbrosse et al. 1976) and that from La Closure at Bissy-sur-Fley to a Charentien de type Ferrassie (Desbrosse and Texier 1973; Parriat 1956).

This diversity in attribution suggests a panoply of different Middle Paleolithic groups. However, as we will see, these different industries have much more in common than the given attributions might suggest. With this contribution, we are beginning to fill in the gaps in comparative analysis in the region, a lacuna that was already criticized 35 years ago: “Malheureusement, pour l’instant, le manque de travaux régionaux dans cette partie de la Bourgogne nous prive de références sur les traits généraux et particuliers des faciès en présence, avec leurs éventuelles ramifications géographiques

” (Pouliquen 1983: 206).

The Characteristics of Middle Paleolithic Assemblages

Raw materials used

With regard to the economic aspects of raw material supply and use strategy, we note that local flint predominates in all Middle Paleolithic assemblages. However, a significant amount of chert is always present (Fig. 2). For example, as regards artifacts from the recently excavated layer GH 3 of Verpillière II, 74% are made of flint from the argiles à silex while only 2% are of chert. In comparison, 85% of the artifacts from the open-air site of La Roche in Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu are made of flint and 12% are made of chert. The highest proportion of chert recognized thus far comes from Grotte de la Mère Grand in Rully, which contains 32% chert artifacts compared to 67% flint artifacts when all pieces are taken into account; indeed, if only the strictly Middle Paleolithic pieces (n=145) are considered, chert use actually increases to 41%. All in all, an average of around 80% of the Middle Paleolithic artifacts are made of locally available flint, and raw material provisioning relies almost exclusively on local or regional sources within a maximum range of 25 km (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, certain specific pieces also suggest long distance imports to the sites. For example, at Verpillière II, at least four pieces can be attributed to raw material sources in the Mont-lès-Etrelles region (Floss 2008, 2009a, 2009b) situated about 110 km to the north-east in the direction of south-western Germany and within the traditional range of the Keilmessergruppen (Frick 2016a).

Assemblage characteristics

In the detailed analysis of recently excavated Late Middle Paleolithic stratified assemblages from Verpillière II at Germolles (e.g., Frick and Floss 2015), Frick (2016a: 657–58) concludes with a list of technological and general features that characterize the studied material:

- Presence of Keilmesser with and without tranchet blow modification (for this feature, see especially Frick et al. this volume)

- Great diversity in the morphology of bifacial objects with a preference for asymmetrical morphologies

- Prevalent use of Levallois reduction for a wide range of blank shapes (from oval to rectangular blanks, triangular and deltoid points and blades)

- Almost no evidence for other elaborate reduction concepts, such as Quina or Discoidal

- In addition to Levallois reduction there is evidence for opportunistic reduction processes to obtain blanks

- Use of ventral reduction on blanks for the configuration of Levallois cores and bulb reduction on tools

- Occasional presence of blades

- Blank tools are made from a wide range of blank morphologies, such as cortical, configuration and target blanks

- Tools can be made on blanks and cores

- Minor presence of Groszaki

- Minor presence of dorsal reduction

- Minor presence of Janus flakes

- Major presence of evidence for hafting processes of a wide range of tools

- “Upper Paleolithic” tool types are more or less non-existent

As listed above, the work of Frick revealed several characteristic features including, among others, the presence of Keilmesser (especially those with a tranchet blow modification) and, in addition, a variety of other bifacial elements such as bifaces of different shape and size or bifacially worked objects (Frick and Floss 2017). With regard to blank production, the predominant use of the Levallois concept is attested, using nodules as well as blanks as core matrices. Very little evidence was observed of other explicit production concepts, such as Discoid or Quina reduction for instance, but there is evidence for a degree of opportunistic production. Bulb reduction was recognizable both on tools, and also in the sense of Kombewa or Levallois-like production. Concerning the general characteristics of the assemblage from Verpillière II, a certain amount of blade production was observed. Furthermore, there are a wide variety of tools made from target blanks but also from cortical or configuration blanks. There is minor evidence for Groszaki pieces and considerable evidence for hafting and re-working of tools. Classic Upper Paleolithic tools (such as burins and endscrapers) are virtually absent from the assemblage.

Using these characteristics of the Verpillière II assemblage as a basis, several surrounding sites have been re-evaluated, and others continue to be reviewed as part of our ongoing research. Frick et al. (this volume) have already pointed out that one major common feature is the presence of Keilmesser, with and without a tranchet blow modification, in at least five of the assemblages (La Roche in Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu, La Closure in Bissy-sur-Fley, La Rue Cataux in Chenôves and the Grottes de la Verpillière I and II). Other bifacial objects are also present at these sites (see Frick et al. this volume). Apart from these Keilmesser-yielding sites, the Middle Paleolithic assemblages of Grotte de la Mère Grand in Rully and En Roche in Germolles provide some additional bifacial objects (n=8 each), and at Saint-Sulpice 10 of these objects were found (Herkert 2020). As regards the site of La Roche, the presence of bifacial tools had already attracted attention at the beginning of the 1980s: “Mais l’originalité de La Roche tient dans la fréquence des objets bifaces

” [But the originality of La Roche lies in the frequency of bifacial objects] (Pouliquen 1983: 206).

Levallois production

While examining blank production in these assemblages, a similar emphasis on Levallois production became evident. The Levallois concept completely dominates the recognizable production strategies. Other concepts like the Discoidal or the Quina concepts are only evidenced in a very limited number of pieces or not at all. In comparison to the identified Discoidal cores, Levallois cores represent between 88 and 100% of the Middle Paleolithic cores (Table 2). Due to uncertain chronological attribution, simple opportunistic flake cores have been excluded from our analysis. Otherwise, exclusively Middle Paleolithic assemblages like Bissy-sur-Fley, for example, or the GH 3 of Grotte de la Verpillière II, contain 37% and 23% Levallois cores, respectively.

While there was a concentration on Levallois production (e.g., Boëda 1993; Boëda et al. 1990; Richter 1997), no dominant production mode is recognizable. In fact, several modes are present to a greater or lesser degree (Fig. 3). The reduction strategies have so far been analyzed for seven assemblages (e.g., Herkert 2020) which provide between n=11 and n=71 Levallois cores for which the mode could be identified (Table 3). As Figure 4 shows, preferential and centripetal reduction are the most dominant modes with means of 30.6% and 34.9%, respectively (Table 3). Repeated unidirectional or bidirectional reduction follows with 13.6% and 13.4%, respectively, while the occurrence of convergent or orthogonal reduction is very limited (mean of 7.6%). This distribution is similar for all analyzed assemblages. Only Verpillière II displays higher values for the repeated uni- and bidirectional reduction (each at 19%), and therefore less preferential (23.8%) and centripetal (28.6%) reduction. In addition, the site of Saint-Sulpice shows a clear peak for repeated unidirectional reduction (25.8%), while preferential reduction was only observed in 19.7% of the pieces; this marks the minimum encountered in all of the assemblages. The minimum values for orthogonal or convergent reduction occur at La Roche where only 2.4% of the cores follow this mode. Here, centripetal reduction was very common (46.3%).

In addition to nodules, which dominate the range of matrices used, blanks were also selected and transformed into Levallois cores; generally, advantage was taken of the existing general shape and the convexities of the blank (e.g., Fig. 3.4 and 3.9). Although the studied assemblages did not attain the same level of blank use as observed at Verpillière II, where n=9 blanks were identifiable as core matrices out of a total of n=24 Levallois cores, using blanks as core matrices is nonetheless an observable strategy present in the other collections. For Saint-Sulpice, there are n=5 Levallois cores which could be identified as blanks. At La Roche, n=3 cores on blanks could be detected within the studied material, and at En Roche at least n=1 of the n=11 cores were configured on a blank.

Levallois products

As for products linked to Levallois production, we observe quite a similar situation within the assemblages. As Frick pointed out for the Levallois products from Verpillière II, elongated forms (Levallois blades) are usually present. A similar observation has been made for the assemblage from Saint-Sulpice in Germolles, where Colbère (1979: 33) already noted that one of the characteristics of the industry is its laminar component.

With the exception of Culles-les-Roches, all other assemblages contain a certain amount of Levallois blades (Fig. 5) and Levallois points. Data are available for eight sites (Table 4). As illustrated in Figure 6, Levallois flakes always dominate the spectrum with a mean of nearly 70%. Levallois blades on average represent about 17% of artifacts that fall within the spectrum of Levallois blanks and reach a maximum at Bissy-sur-Fley (35.2%). For the assemblage from Saint-Sulpice, 27.5% of its Levallois products are comprised of blades. In addition to Culles-les-Roches, where no blades have been identified so far, a minimum is provided at En Roche (Germolles), where only 7.1% of the Levallois products could be identified as blades. Triangular forms, in the sense of Levallois points (and pseudo-Levallois points), reach a mean of almost 14%. Perceptible peaks can be observed for Chenoves and Culles-les-Roches, where the proportion of points reaches 26.5% and 22.9%, respectively.

For the preparation of the detachment of Levallois products, flat and facetted butts are clearly preferred (Table 5 and Fig. 7). At La Roche, more than 86% of the identified butts fall into these two categories. The same is true for En Roche, where flat and facetted butts together reach 83%, with a slightly different emphasis than that observed at La Roche. At Verpillière II, there is also a distinct preference for flat and facetted platforms, while the majority of the blanks show facetted butts. This phenomenon has also been observed for the entire lithic blank production from GH 3 at Verpillière II (Frick 2016a: 609–10). A similar picture emerges where recent data are available for the Levallois core platforms. The n=11 cores from En Roche show either a flat striking platform (n=5) or a facetted one (n=6). La Roche, in contrast, provides almost exclusively facetted core platforms (n=38 to n=3 flat platforms), which does not in fact correlate with the image of the corresponding blanks but at the same time does not entirely contradict it. Furthermore, there seems to be no further correlation or preference for one or other of these two platform styles in terms of, for example, ongoing reduction, in regards to either core or to blank sizes.

General appearance

Within the more general appearance of the assemblages, further common features can be observed. At most of the sites, tool production is not restricted to target blanks, as is the case at Verpillière II. In fact, tools are made from a huge variety of blanks, including, next to target blanks, configuration blanks and initialization blanks (i.e., cortical blanks). Where sufficient data are available, this pattern could be observed for all of the assemblages studied. La Closure, where studies are still in progress, is an exception. This type of opportunistic matrix selection for tool production could be related to economic strategies governing raw material use patterns.

Another commonly observable trait is the intentional removal of bulbs on many tools (Table 6). Even though not extensively applied, this feature concerns 5.5% of the modified blanks at La Roche and 6.8% of those at En Roche, respectively. The studied material from Verpillière II reaches a value of 4.5% for bulb reduction within the spectrum of modified blanks. Bulb reduction on tools has also been observed within the assemblages of some other surrounding sites, although quantitative data are lacking (e.g., Verpillière I, La Mère Grand, Saint-Sulpice and La Folatière).

The removal of bulbs might be related to, among others, the manipulation or hafting of the tools concerned (Banks 2004; Rots 2010, 2016). Furthermore, there are other “morphological adjustments” evident on the tools that provide “indirect arguments” (Rots 2016: 168) for the practice of hafting. In addition to bulb removal (or ventral face flattening), we observe opposite lateral notches as well as uni- and bifacial retouch on one or both of the edges (Fig. 8). These observations also provide evidence for specific activities carried out on site, such as re-working and rehafting of tools. While edge-modified basal fragments, for example, represent the hafting remains of supposed composite tools, there are also, as Frick (2016a) demonstrated, fragments that only display a modified active edge (tool tips). Such tool tips complement the hafting evidence.

1-3) Scrapers (flint from argiles à silex) showing different reduction stages (1: Bonnotte collection, 2-3 Donguy collection); 4) Heavily reduced scraper (rose chert, Donguy collection); 5) Scraper (flint from argiles à silex) with two proposals of hafting (Denon collection), a: hafting with rounded active edge; b: hafting as regular scraper; 6) Point or convergent scraper (grey chert, Donguy collection); 7) Point or convergent scraper (flint from argiles à silex, Denon collection); 8) Rounded end scraper (rose chert, Donguy collection) on Levallois blade; 9) Rounded end scraper (rose chert, Donguy collection); 10) End scraper (brown flint, Donguy collection); 11) End scraper (pale chert, Denon collection) on Levallois blade; 12-15) Basal fragments of Levallois blades (flint from argiles à silex) with lateral retouch or notches (Bonnotte collection); 16) Basal blank fragment (flint from argiles à silex) with lateral retouch (Donguy collection) (photos: Herkert and Huber; image: Herkert).

Technological cluster

Concerning the other general features set out by Frick (2016a), analysis is still in progress (see also Herkert and Frick 2020); in some cases the lack of stratigraphical contexts for the pieces prevents further clarification. Nevertheless, the initial overview of the assemblages appears quite homogeneous (Table 7), which leads us to the hypothesis of a technological cluster on these sites. The major common feature on which this assumption is based is the presence of various bifacial objects including Keilmesser with and without tranchet blow (see also Frick et al. this volume) as well as a homogeneous pattern of lithic production evident in the prevalent use of the Levallois concept, on the one hand, and the almost complete absence of other specific reduction concepts, on the other hand. Furthermore, these technological traits are accompanied by a general homogeneous ‘habitus’ in the assemblages, composed of laminar blanks, opportunistic tool manufacturing on a multitude of blanks (including target blanks and other debitage blanks), bulb reduction on tools and further indications for tool hafting.

Thus far, radiometric dates obtained by IRSL, ESR and AMS-14C have been used to establish a chronological framework for Verpillière I (GH 15) and Verpillière II (GH 3 and 4) (Heckel et al. 2016; Richard et al. 2016; Zöller and Schmidt 2016). These dates place the Middle Paleolithic assemblages of these two neighboring sites within the probability range between 62 and 42 ka BP (Fig. 9). On the basis of the technological traits, we presume that the other assemblages fall within the same chronological bracket, but further work is required and is currently in progress. Nevertheless, especially within the context of an affiliation of these industries to the Keilmessergruppen (Frick 2016a; Frick and Floss 2017; Frick et al. intra), it seems likely that the other assemblages also belong to the Late Middle Paleolithic (Frick et al. 2017).

Spatial Organization

In the context of the observed technological correlation between the assemblages and given that “[s]ite patterning in both within-place and between-place contexts is a property of the archaeological record” (Binford 1982: 6), recent research in the Côte Chalonnaise region provides further evidence of potential regional inter-site organization of late Middle Paleolithic land-use patterns as well as of high resolution intra-site spatial distribution patterns.

Inter-site functionality: a hypothesis

Given that the research area constitutes a dense micro-regional concentration of caves, rockshelters and open-air sites with different raw materials available in close proximity (Fig. 1), the assemblages differ in terms of qualitative and quantitative composition (e.g., tool frequencies). Due to these differences, and with regard to the geographical distribution, the topological position, and the extent of the sites, we propose a hypothetical regional functional model (Fig. 10).

Both Verpillière sites have been interpreted as base camps (Fig. 10a) with extensive assemblages, which have produced evidence for in-situ lithic production as well as recycling and re-working of tools and abundant food waste (Frick 2016a, 2016b; Frick and Floss 2015; Herkert et al. 2015; Litzenberg 2015).

At Saint-Sulpice in Germolles and Les Griffières in Fontaines, two probable workshops (Fig. 10b) with extensive lithic production are situated on flint outcrops (Colbère 1979; Pascal 2013; Sikner 2014).

La Roche at Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu is a very large open-air site (Herkert 2020; Herkert et al. 2015; Pouliquen 1982, 1983). Lithic production is in evidence here, but with a focus on scraper production (constituting nearly 40% of the known Middle Paleolithic material), which might indicate a specialized processing site (Fig. 10c).

Finally, there are smaller satellite sites in the surrounding area (Fig. 10d) that have yielded smaller assemblages. Particularly noteworthy are the small cave sites of La Mère Grand in Rully and Les Teux Blancs in Saint-Denis-de-Vaux whose elevated locations provide a very good overview over the whole region. In contrast, En Roche is situated on the plain.

Intra-site organization

GH 16 at Verpillière I

During the excavation of Verpillière I, preserved parts of an intact Middle Paleolithic layer (GH 16) were detected between 2010 and 2015 in the inner part of the cave (Floss 2011, 2012; Floss et al. 2013b, 2014, 2016). The area makes up 15 m² of the excavation grid (Fig. 11). The character of the lithic industry, although quantitatively limited, is not without analogies to those from Verpillière II or other surrounding sites. In addition to opportunistic flake cores, Levallois production has been observed. The spectrum also comprises elongated forms as well as a quantity of bifacial objects (Litzenberg 2015). Radiometric dating (AMS-14C and ESR/U-Th) of the overlying GH 15 provides indications for a terminus ante quem at around 48 ka BP (Heckel et al. 2016; Richard et al. 2016). Faunal remains that include deer (Cervus elaphus and Megalocerus giganteus), reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), horse (Equus ferus), bison (Bison priscus), fox (Vulpes vulpes), and lynx (Lynx spelaea) support a chronological attribution to between MIS4 and early MIS3, within a temperate phase of the early or middle Weichselian glaciation.

Despite the limited extent of the preserved area, the analysis of the find distribution provides initial evidence for distinct concentrations and thus for spatial organization within the various occupation events. As Litzenberg (2015) points out, the main concentrations of lithic artifacts and faunal remains overlap each other. Nevertheless, indications for anthropogenic zonal structuring are present, especially in the case of the distribution of cores and raw pieces (Fig. 11). Cores and raw pieces are mainly concentrated in an area covering only half a square meter (square number 191/097), with cores generally found in the southern part of the area and raw pieces in the northern part. The spatial distribution of blanks does not indicate primary knapping events in this part of the site, although quartzitic hammerstones have also been found. Furthermore, given that the rear of the former rockshelter is not the most suitable place for knapping activities, the deposition of the pieces can instead be interpreted as the storage of raw materials for use in future re-visits to the site within a pattern of repeated seasonal migration (e.g., Binford 1980, 1982) or as “insurance gear” (Binford 1979). This indicates economic organization on the part of late Middle Paleolithic Neanderthals in the region.

GH 3 at Verpillière II

Another reliable source for intra-site organization, spatial patterning and the identification of occupation features dating to the late Middle Paleolithic in southern Burgundy concerns the stratified deposits of GH 3 at Verpillière II (Frick 2016a, 2016b).

The identification of several distinct charcoal lenses in the otherwise very homogeneous deposits of GH 3 (Fig. 12a) not only indicates homogeneous, low-energy, proximate aeolian sedimentation, resulting in the transportation of lighter burnt material from presumed hearths located at the entrance of the former rockshelter into the interior (Frick 2016b: 707), but also suggests that several repeated occupation events, which would have included the use of fire, occurred over the course of this period of constant sedimentation. Furthermore, the charcoal concentrations are clearly separate from the recorded limestone fragments (Fig. 12b).

A second detected pattern at Verpillière II concerns the spatial distribution of lithic artifacts and faunal remains. As already presented elsewhere (Frick 2016a, 2016b), these two categories display a clear spatial separation from each other (Fig. 12c). While lithic artifacts are primarily scattered towards the eastern part of the excavation area and thus also towards the former opening of the ancient rockshelter, the faunal remains, in contrast, are mostly concentrated in the inner part of the cavity in the west and south of the excavated area.

Comparable observations have been made on other sites, such as Abric Romaní or Kebara Cave (Carbonell i Roura 2012; Speth et al. 2012). “If we assume that the main occupation occurred under the rock shelter, the far interior of the shelter and the area of the cave tunnel make logical areas for toss-zones and rubbish dumping, further from the active occupation area and less likely to attract carnivores” (Frick 2016b: 708).

These observations are, to a certain extent, in contrast to those made for Verpillière I (GH 16). On the one hand, no separation between fauna and lithics has been observed here; on the other hand, there are no deposit-like features in Verpillière II.

Discussion

The Middle Paleolithic archaeological record of the Côte Chalonnaise region allows multifocal analyses on a regional scale. The recently conducted excavations at Verpillière I and II provide high resolution data for microscale intra-site analysis that may serve as a reliable reference and starting point for further investigation. As demonstrated, the stratified assemblages contribute significantly to our understanding of the technological particularities within an observable variability. Initial radiometric dating provides further evidence for a chronological position in the late Middle Paleolithic, around the end of MIS 4 and the beginning of MIS 3.

The comparative studies of neighboring sites in the area, which we have recently commenced, reveal a multitude of common features despite the lack of stratigraphical context. Such mesoscopic regional research is crucial for understanding the structuring of late Middle Paleolithic settlement. The homogeneous patterning discovered contrasts with the former fairly heterogeneous image of the Middle Paleolithic record that emerged through typological assignments. In this context, we have to once again stress the identification of several assemblages containing Keilmesser with and without tranchet blow (Frick et al. 2018; Frick et al. 2017, also this volume; Herkert et al. 2015). Despite all of the production variability observed, this litho-technological correspondence within the industries links them to a plausible site cluster present in a region which is on the margins of the traditional circumjacent late Middle Paleolithic techno-complexes or facies (Fig. 13). This comparative regional analysis is an indispensable step for macroscopic considerations.

Our research has only just begun, and the identified presence of Keilmesser already enlarges the traditional extent of the central-eastern European Keilmessergruppen complex further to the west. Other lithic elements, such as various bifacial objects, have already led to other attributions for the Verpillière I assemblage, such as a Charentian with Micoquian influence, or, in a broader scale, to a Mousterian with Bifacial Tools (MBT) with affinities even to a Mousterian of Acheulian Tradition (MTA) (Koehler 2009; Ruebens 2012, 2013). To date, no definite attribution of the different assemblages can to be made. But rather than defining a discrete technocomplex, we propose to see the southern Burgundy site cluster in terms of a regional “style zone” (Binford 1965: 208), embedded in and reflecting the technological traditions of the surrounding space-time units and thus demonstrating the “[…] typo-technological and spatio-temporal variability” (Ruebens 2013: 349) of late Middle Paleolithic behavior.

Conclusion

We provide a comparative overview of a number of Middle Paleolithic assemblages from the Côte Chalonnaise that reveals quite homogeneous characteristics. The presence of bifacial objects, and, therein, particularly the presence of Keilmesser (with tranchet blow), embedded in a nearly exclusively Levallois-based blank production with a laminar component, strongly suggest a litho-technological linked site cluster. In total, five sites out of ten feature Keilmesser within their assemblages and four more contain bifacial elements (Table 7). The Levallois production shows a clear predilection for preferential and centripetal reduction (Fig. 4). On a regional scale, initial indications emerge regarding inter-site functionality within the ranged habitat. High resolution data from stratified deposits show further evidence for spatial intra-site organization within the region. There, the example of Verpillière I demonstrates spatial patterning for lithic production purposes (Fig. 11). At Verpillière II, a distinct deposition of faunal remains and lithic artifacts indicates intended zoning within the occupation area (Fig. 12). Located on the margins of surrounding traditional late Middle Paleolithic techno-complexes, the research area is judged crucial to further our understanding of the relationship and possible interplay between these lithological facies at the end of MIS4 and the beginning of MIS3.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank H. Koehler for initiating and organizing the conference “The Rhine during the Middle Paleolithic: Boundary or Corridor?,” from which this article originates. Further thanks go to those who support and contribute to our research in Burgundy.

Research presented in this paper was financed in the course of the DFG CRC 1070 “RessourcenKulturen” at the University of Tübingen, the DFG project FL 244/5-2 and the PCR “Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale,” UMR 6298 ARTeHIS, affiliated with the Université de Bourgogne, Dijon.

Cordial thanks also go to Dominique Rose for her patient English revision. Furthermore, we would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers, whose excellent remarks greatly helped transform the initial manuscript into a paper worthy of publication.

Literature

Banks, W. E. 2004. Toolkit Structure and Site Use: Results of a High-Power Use-Wear Analysis of Lithic Assemblages from Solutré (Saône-et-Loire), France. Dissertation, University of Kansas.

Binford, L. R. 1965. Archaeological Systematics and the Study of Culture Process. American Antiquity 31 (2, Part 1): 203–10.

Binford, L. R. 1979. Organization and Formation Processes: Looking at Curated Technologies. Journal of Anthropological Research 35 (3): 255–73.

Binford, L. R. 1980. Willow Smoke and Dogs’ Tails: Hunter-Gatherer Settlement Systems and Archaeological Site Formation. American Antiquity 45 (1): 4–20.

Binford, L. R. 1982. The Archaeology of Place. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1: 5–31.

Boëda, E. 1993. Le débitage discoïde et le débitage Levallois récurrent centripède. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 90 (6): 392–404.

Boëda, E. 2013. Technologique & Technologie. Une Paléohistoire des objets lithiques tranchants. Paris: @rchéoéditions.com.

Boëda, E., J.-M. Geneste, and L. Meignen. 1990. Identification de chaînes opératoires lithiques du Paléolithique ancien et moyen. Paléo 2: 43–80.

Carbonell i Roura, E., ed. 2012. High Resolution Archaeology and Neanderthal Behavior: Time and Space in Level J of Abric Romaní (Capellades, Spain). New York: Springer.

Colbère, L.-G. 1979. Le Site Moustérien et Néolithique de Germolles-Saint-Sulpice (Sâone-et-Loire). Revue Archéologique de l’Est et du Centre-Est 30: 25–45.

Combier, J. 1956. La grotte des Teux-Blancs à Saint-Denis-des-Vaux (Saône-et-Loire. Acheuléen supérieur – Moustérien – Magdalénien. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologique de Chalon-sur-Saône 24 (1er fascicule): 46–56.

Combier, J. 1959. Circonscription de Lyon. Gallia préhistoire 2: 109–33.

Combier, J., and P. Ayroles 1976. Gisements Paléolithiques de Chalonnais. In IX ième congrès de l‘ U.I.S.P.P. Livret-guide de l’excursion A8, Bassin du Rhone, Paléolithique et Néolithique, ed. by J. Combier and J.-P. Thevenot, pp 85–6. Nice.

Desbrosse, R., J. K. Kozlowski, and J. Zuate y Zuber. 1976. Prodniks de France et d’Europe Centrale. L’Anthropologie (Paris) 80 (3): 431–48.

Desbrosse, R., and J.-P. Texier. 1973. La Station Moustérienne de Bissy-sur-Fley (S.-et-L.). La Physiophile 78: 8–31.

Dutkiewicz, E. 2011. Die Grotte de La Verpillière I – 150 Jahre Forschungsgeschichte. Die Aufarbeitung und Auswertung der Altgrabungen des paläolithischen Fundplatzes Germolles (Commune de Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire, Frankreich). Magister’s Thesis, University of Tübingen.

Dutkiewicz, E., and H. Floss. 2015. La Grotte de la Verpillière I à Germolles, site de référence Paléolithique en Bourgogne méridional. Historique des 150 ans de recherche. La Physiophile 162: 13–32.

Farizy, C. 1995. Bissy-sur-Fley (Saône-et-Loire): Site paléolithique moyen de La Clôsure, Sondages d’évaluation, campagne de 1994, Rapport de prospection thématique. Unpublished report, Dijon, S.R.A. Bourgogne.

Ferry, H. d., and A. Arcelin. 1868. L’Age du Renne en Mâconnais. Mémoire sur la station du Clos du Charnier à Solutré (Saône-et-Loire). Mâcon: Imprimerie d’Emile Protat.

Floss, H. 2005a. Das Ende nach dem Höhepunkt. Überlegungen zum Verhältnis Neandertaler- anatomisch moderner Mensch auf Basis neuer Ergebnisse zum Paläolithikum in Burgund. In Vom Neandertaler zum Modernen Menschen, ed. by N. J. Conard, S. Kölbl, and W. Schürle, pp. 109–30. Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke Verlag.

Floss, H. 2005b. Prospections systématiques aux alentours des sites paleolithiques de Rizerolles à Azé. In 1954-2005 Recherches achéologiques en Mâconnais, ed. by Groupement Archéologique du Mâconnais (G.A.M.), pp. 23–8. Mâcon.

Floss, H. 2007. Rapport de fouille programmée. Lieu-dit: Grotte de La Verpillière à Germolles Commune: Mellecey (71), Durée de l’opération: 17 – 30 septembre 2006. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H. 2008. Rapport de fouille programmée. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles Commune : Mellecey (71); Durée de l’opération : 27 août – 21 septembre 2007. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H. 2009a. Rapport de fouille programmée. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles Commune: Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71); Durée de l’opération : 25 août – 20 septembre 2008. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H. 2009b. Rapport de fouille programmée. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles Commune: Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71); Durée de l’opération : 27 juillet – 18 septembre 2009. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H. 2011. Rapport de fouille pluriannuelle 2010-2012. Rapport intermédiaire 2010. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles. Commune: Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71); Durée de l’opération: 25 juillet – 18 septembre 2010. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H. 2012. Rapport de fouille pluriannuelle 2010-2012. Rapport intermédiaire 2011. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles. Commune: Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71); Durée de l’opération: 25 juillet – 16 septembre 2011. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H., C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, C. Heckel, and K. Herkert. 2013a. La Grotte de la Verpillière II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Fouille programmée 2010-2012. Rapport annexe. Complément suite à la CIRA du février 2013. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H., C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, C. Heckel, and K. Herkert. 2013b. Rapport de fouille pluriannuelle 2010-2012. Rapport final et rapport 2012. Lieu-dit: Les Grottes de La Verpillière I et II à Germolles. Commune: Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71); Durée de l’opération: 29 juillet – 21 septembre 2012. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H., C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, C. Heckel, and K. Herkert. 2014. Les Grottes de la Verpillière à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Fouille programmée pluriannuelle 2013-2015. Rapport intermédiaire 2013. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H., C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, K. Herkert, and N. Huber. 2016. Fouilles programmées pluriannuelles aux sites paléolithiques des Grottes de la Verpillière I & II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Rapport annuel 2015 – Rapport pluriannuel 2013 à 2015. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Floss, H., C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, K. Herkert, and N. Huber. 2017. Fouilles programmées pluriannuelles aux sites paléolithiques des Grottes de la Verpillière I & II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Rapport annuel 2016. Unpublished report, Tübingen.

Frick, J. A. 2010. Les Outils du Néandertal. Technologische und typologische Aspekte mittelpaläolithischer Steinartefakte, am Beispiel der Grotte de la Verpillière I bei Germolles, Commune Mellecey, Saône-et-Loire (71), Frankreich. Magister’s Thesis, Universität Tübingen.

Frick, J. A. 2014a. Le paléolithique moyen de la Côte chalonnaise. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 17–24. Tübingen.

Frick, J. A. 2014b. Les travaux à la Grotte de la Verpillière II en 2014. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 99–155. Tübingen.

Frick, J. A. 2016a. On Technological and Spatial Patterns of Lithic Objects. Evidence from the Middle Paleolithic at Grotte de la Verpillière II, Germolles, France. Dissertation, Universität Tübingen.

Frick, J. A. 2016b. Visualizing Occupation Features in Homogenous Sediments. Examples from the Late Middle Palaeolithic of Grotte De La Verpillière II, Burgundy, France. In CAA 2015. Keep the Revolution Going. Proceedings of the 43rd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, vols. 1 & 2, ed. by S. Campana, R. Scopigno, G. Carpentiero, and M. Cirillo, pp. 699–713. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Frick, J. A. 2017. Rapport de fouille programmée de la campagne de 2016 au Grotte de la Verpillière II. In Fouilles programmées pluriannuelles aux sites paléolithiques des Grottes de la Verpillière I & II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Rapport annuel 2016, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, K. Herkert, and N. Huber, pp. 55–98. Tübingen.

Frick, J. A., and H. Floss. 2015. Grotte de la Verpillière II. Preliminary Insights from a New Middle Paleolithic Site in Southern Burgundy. In Forgotten Times, Spaces and Livestyles, ed. by S. Sázelova, M. Novak, and A. Mizerova, pp. 53–72. Brno: Institute of Archaeology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Masaryk University.

Frick, J. A., and H. Floss. 2017. Analysis of Bifacial Elements from Grotte de la Verpillière I and II (Germolles, France). Quaternary International 428 (Part A): 3–25.

Frick, J. A., and K. Herkert. 2014. Lithic Technology and Logic of Technicity. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 23: 129–72.

Frick, J. A., K. Herkert, C. T. Hoyer, and H. Floss 2018. Keilmesser with tranchet blow from Grotte de la Verpillière I (Germolles, Saône-et-Loire, France). In Multas per Gentes et Multa per Saecula. Amici Magistro et Collegae suo loanni Christopho Kozłowski dedicant, ed by P. Valde-Nowak, K. Sobczyk, M. Nowak and J. Źrałka, pp. 25-36. Kraków: Alter Publishing House.

Frick, J. A., K. Herkert, C. T. Hoyer, and H. Floss. 2017. The Performance of Tranchet Blows at the Late Middle Paleolithic Site of Grotte de la Verpillière I (Saône-et-Loire, France). Plos One 12 (11): 1–44.

Frick, J. A., and S. P. Steigerwald. 2016a. Grotte de la Verpillière II: Rapport pluriannuelle 2013-2015. In Rapport de fouille programmée pluriannuelle 2013 à 2015 aux sites paléolithiques des Grottes de la Verpillière I et II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Rapport annuel 2015 – Rapport pluriannuel 2013-2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, K. Herkert, and N. Huber, pp 278–359. Tübingen.

Frick, J. A., and S. P. Steigerwald. 2016b. Rapport des activites à la Grotte de la Verpillière II: Pendant la campagne de 2015. In Rapport de fouille programmée pluriannuelle 2013 à 2015 aux sites paléolithiques des Grottes de la Verpillière I et II à Germolles, commune de Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire). Rapport annuel 2015 – Rapport pluriannuel 2013-2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, K. Herkert, and N. Huber, pp 219–77. Tübingen.

Gros, A.-C. 1964. La Vallée des Vaux et les stations préhistoriques de St-Martin-sous-Montaigu (S.-et-L.). L’Eduen – Bulletin trimestriel de la Société d’Histoire Naturelle d’Autun 6: 9–13.

Gros, O., and A.-C. Gros. 2005. Le Chalonnais Préhistorique. Collections du Musée de Chalon-sur-Saône. Chalon-sur-Saône.

Guillard, E. 1947. La station paléolithique de la “Roche” à Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologique de Chalon-sur-Saône 32 (1): 48–60.

Guillard, E. 1954. Une Station Aurignacienne Inédite à Germolles. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologique de Chalon-sur-Saône 33 (2): 129–38.

Guillard, E. 1959. Note sur les Stations et Vestiges Préhistoriques de la Côte Chalonnaise trouvés à Chenoves, Saules et à I’Est de Culles-les-Roches. La Physiophile 50: 2–15.

Guillard, E. 1960. Note sur les Stations et Vestiges Préhistoriques de la Côte Chalonnaise trouvés à Chenoves, Saules et à I’Est de Culles-les-Roches. Le Gisement Préhistorique de la Rue Cataux (Chenôves). La Physiophile 52: 5–16.

Heckel, C., T. Higham, H. Floss, and C. T. Hoyer. 2016. Radiocarbon Dating of Verpillière I and II. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 30–7. Tübingen.

Herkert, K. 2014. Prospections archéologiques en Côte Chalonnaise. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 255–77. Tübingen.

Herkert, K. 2016. Réévaluation des collections paléolithiques de la Côte Chalonnaise en dépôt des musées. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 51–67. Tübingen.

Herkert, K. 2017. L’industrie lithique de Germolles en Roche. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2016, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 47–60. Tübingen.

Herkert, K. 2020. Das späte Mittel- und frühe Jungpaläolithikum der Côte Chalonnaise. Betrachtungen zu litho-technologischen Verhaltensweisen nebst forschungsgeschichtlicher Erörterungen – Eine Bestandsaufnahme. Dissertation, Universität Tübingen.

Herkert, K., B. Macioszczyk, and H. Floss. 2016a. Prospections à Germolles en Roche. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp 98–105. Tübingen.

Herkert, K., and J. A. Frick 2020. Technological features in the late Middle Paleolithic of the Côte Chalonnaise (Burgundy, France). Lithikum 7-8: 31-50.

Herkert, K., M. Siegeris, J.-Y. Chang, N. J. Conard, and H. Floss. 2015. Zur Ressourcennutzung später Neandertaler und früher moderner Menschen. Fallbeispiele aus dem südlichen Burgund und der Schwäbischen Alb. Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft für Urgeschichte 24: 141–72.

Herkert, K., M. Siegeris, N. J. Conard, and H. Floss. 2016b. A Question of Availability and Quality. Curse and Blessing of Lithic Raw Materials and their Use during the Late Middle Paleolithic and the Early Upper Paleolithic. SFB 1070 RessourcenKulturen: Resources in social Context(s): Curse, Conflicts and the Sacred, International Conference June 13 – 15, Tübingen. Poster presentation, Tübingen.

Hoyer, C. T., K. Herkert, J. A. Frick, M. Siegeris, and H. Floss. 2014a. Landscape and Habitat – the Côte Chalonnaise (Burgundy, France), a Palaeolithic Micro-Regional Case Study. In Book of Abstracts, ed. by J. L. Asuaga Ferreras, J. M. Bermúdez de Castro, and E. Carbonell i Roura, pp. 246–7. Burgos: UISPP 2014 Burgos.

Hoyer, C. T., N. Huber, and H. Floss. 2014b. La Grotte de la Verpillière I. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 49–98. Tübingen.

Koehler, H. 2009. Comportements et identité techniques au Paléolithique moyen dans le Bassin parisien: Une question d’échelle d’analyse? Dissertation: Université de Paris Ouest-Nanterre La Défence.

Lafond, M. 1947. Fouilles recentes à la caverne de Culles-les-Roches. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Chalon-sur-Saône 32 (1): 61–7.

Lafond, M. 1957. Trois fouilles à Culles-les-Roches. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Chalon-sur-Saône 34 (2): 9–11.

Lènez, L.-A. 1926. Une nouvelle station du Paléolithique supérieur dans l’arrondissement de Chalon-sur-Saône. L’Homme Préhistorique 13e année (No 11): 231–45.

Lènez, L.-A. 1935. La Grotte à ossements Quaternaires des Teux-Blancs, commune de Saint-Jean-de-Vaux. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Chalon-sur-Saône 26: 115–8.

Litzenberg, R. 2015. Materialübergreifende Analyse des GH 16 der Grotte de la Verpillière I in Germolles, Gemeinde Mellecey (Saône-et-Loire, Frankreich). Bachelor’s Thesis, Universität Tübingen.

Macioszczyk, B., and V. Donguy. 2014. Germolles en Roche (Prospection de surface). In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 288–97. Tübingen.

Mayet, L., J. Mazenot, and E. Menand. 1921. Les stations préhistoriques de la vallée de l’Orbize. In Comte Rendu de la 44me Session – Strasbourg 1921, ed. by Association Française pour l’Avancement des Sciences (A.F.A.S.), pp. 491–2. Paris: Secrétariat de l’Association et MM. Masson.

Méray, C. 1869. L’âge de la pierre à Germolles. Matériaux d’Archeólogie et d’Histoire par MM. les Archéologues de Saône-et-Loire et des Départements limitrophes 1 (6 & 7): 83–6.

Méray, C. 1876. Fouilles de la caverne de Germolles. Commune de Mellecey. Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Chalon-sur-Saône 6: 251–66.

Mortillet, G. d. 1883. Le Préhistorique. Antiquité de l’Homme. Paris: C. Reinwald.

Parriat, H. 1956. Une station moustérienne inédite. La Physiophile 45: 9–16.

Pascal, M.-N. 2013. Bourgogne, Saône-et-Loire, Mellecey, “Rue du Petit Puits.” Rapport de diagnostic archéologique. INRAP Grand Est sud. Unpublished report, Dijon.

Pautrat, J.-Y. 2016. Un point sur l’inventaire des sites paléolithiques en Bourgogne méridionale (Saône-et-Loire), à partir de la carte archéologique régionale. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 119–25. Tübingen.

Pouliquen, C. 1982. Le Moustérien de La Roche à Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu (Saône-et-Loire). Collection Lènez au Musée Denon à Chalon-sur-Saône. Diplome d’Études Supérieures, Bordeaux: Université de Bordeaux.

Pouliquen, C. 1983. Le Moustérien de La Roche à Saint-Martin-sous-Montaigu (Saône-et-Loire) d’après la collection Lènez au Musée Denon à Chalon-sur-Saône. Revue Archéologique de l’Est et du Centre-Est Dijon 133 (3-4): 183–207.

Richard, M., C. Falguères, B. Ghaleb, and D. Richter. 2016. Résultats préliminaires des datations par ESR/U-Th sur émail dentaire, Grottes de la Verpillière I et II. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 11–23. Tübingen.

Richter, J. 1997. Sesselfelsgrotte III. Der G-Schichten-Komplex der Sesselfelsgrotte. Zum Verständnis des Micoquien. Quartär-Bibliothek 7. Saarbrücken: Saarbrückener Druckerei und Verlag.

Rots, V. 2010. Prehension and Hafting Traces on Flint Tools. A Methodology. Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Rots, V. 2016. Projectiles and Hafting Technology. In Multidisciplinary Approaches to the Study of Stone Age Weaponry, ed. by R. Iovita and K. Sano, pp. 167–85. Dordrecht: Springer. Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology.

Ruebens, K. 2012. From Keilmesser to Bout Coupé Handaxes: Macro-Regional Variability among Western European Late Middle Palaeolithic Bifacial Tools. Dissertation, University of Southampton.

Ruebens, K. 2013. Regional Behaviour among Late Neanderthal Groups in Western Europe: A Comparative Assessment of Late Middle Palaeolithic Bifacial Tool Variability. Journal of Human Evolution 65 (4): 341–62.

Seitz, R. 2011. Ein Biface mit Loch aus der Fundstelle Les Griffières (Gde. Fontaines, Saône-et-Loire, Frankreich). Ein Beitrag zur kulturellen Modernität der Neandertaler. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universität Tübingen.

Siegeris, M. 2014. Report about the Fieldwork in Southern Burgundy, 2014. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 244–54. Tübingen.

Siegeris, M. 2020. Lithische Rohmaterialien im südlichen Burgund und auf der Schwäbischen Alb vom späten Mittel- bis zum frühen Jungpaläolithikum. Dissertation, Universität Tübingen.

Siegeris, M., and H. Floss. 2015. Characterizing Jurassic Cherts as a Lithic Raw Material in the Middle to Upper Paleolithic of Southern Burgundy, France. In International Symposium on Knappable Materials “On the Rocks.” Barcelona, 7-12 September 2015, University of Barcelona. Abstracts Volume, ed. by X. Mangado, O. Crandell, M. Sánchez, and M. Cubero, p. 127. Barcelona: SERP, Universitat de Barcelona.

Sikner, F. 2014. Le site des Griffières à Fontaines (Saône-et-Loire). In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2014, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 282–7. Tübingen.

Soressi, M., and M. Roussel. 2014. European Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transitional Industries: Châtelperronian. In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, ed. by C. Smith, pp. 2679–93. Springer New York.

Speth, J. D., L. Meignen, O. Bar-Yosef, and P. Goldberg. 2012. Spatial Organization of Middle Palaeolithic Occupation X in Kebara Cave (Israel): Concentrations of Animal Bones. Quaternary International 247: 85–102.

Zöller, L., and C. Schmidt. 2016. Germolles – Grotte de la Verpillière II – GH 3 & 4, Report on Luminescence Dating of Cave Sediments. In Projet Collectif de Recherche – Le Paléolithique supérieur ancien en Bourgogne méridionale. Genèse, chronologie et structuration interne, évolution culturelle et technologique. Rapport annuel 2015, ed. by H. Floss, C. T. Hoyer, J. A. Frick, and K. Herkert, pp. 45–9. Tübingen.