Zusammenfassung

Die Lebensgeschichte des Menschen unterscheidet sich von der unserer nächsten lebenden Verwandten, den Menschenaffen. In mancher Hinsicht hat sie sich verlangsamt durch z.B. erhöhte Langlebigkeit oder dem späteren Alter bei der ersten Fortpflanzung, während sie sich in anderer Hinsicht beschleunigt hat wie beim früheren Alter der Mutter beim Abstillen. Die Evolution unserer spezifischen Muster von Wachstum, Entwicklung und Fortpflanzung ist jedoch nach wie vor unzureichend verstanden. In diesem Artikel möchte ich zunächst die offensichtlichen Merkmale der menschlichen Lebensgeschichte überprüfen. Anschließend hebe ich wichtige ungelöste Fragen bezüglich ihrer Evolution hervor, beispielsweise die von kurzen Geburtenabständen oder einer signifikanten postreproduktiven Lebensspanne von Frauen. Abschließend möchte ich einen Überblick über die biologischen Strukturen – hauptsächlich Knochen und Zahnzement – geben, die zur Rekonstruktion und Schätzung des Zeitpunkts von Ereignissen im Erwachsenenleben verwendet werden können, und vielversprechende Richtungen für zukünftige Forschungen zu diesem Thema skizzieren.

Human life history

Humans are part of the great ape clade and are the only extant species of the genus Homo. Although there is some variation within our species, the life history profile of Homo sapiens is notably distinct from that of our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, and is likely derived from our last common ancestor (LCA) (Bribiescas 2020; Hill and Kaplan 1999; Kaplan et al. 2000; Mace 2000; Robson et al. 2006; Robson and Wood 2008; B. H. Smith and Tompkins 1995; Volk 2023). Understanding how, when, and in response to which selective pressures this unique life history profile evolved remains a key question in evolutionary anthropology.

Over the years, research on hunter-gatherer populations has provided valuable insights into the human life history profile in conditions that resemble those predating agriculture and modern medicine (Volk 2023). These populations offer a glimpse into the reproductive profiles, population densities, and mortality patterns that shaped our species’ development before the advent of agriculture and medical advancements (Mace 2000; Page et al. 2018, 2024, 2025; Robson et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2006).

One of the most striking features of human life history is our extended lifespan, which cannot be explained by an increase in body size. Hunter-gatherer populations have a modal observed lifespan ranging from 68 to 79 years (Gurven and Kaplan 2007), while other great apes typically have maximum lifespans of 50 years in bonobos to 58 years in orangutans (Robson et al. 2006). Human longevity is primarily the result of reduced adult mortality, which derives from a combination of genes, environment, resiliency, and chance (Pignolo 2019), and it has been argued to being a self-reinforcing and positively-selected life-history trait (Carey and Judge 2001). However, for selection to favor slower rates of aging—characterized by declining physiological performance—the fitness benefits of maintaining physical performance must outweigh the costs of increased energy expenditure for maintenance and repair. While comparative primate data on aging progression is still limited, recent studies are expanding rapidly (Colchero et al. 2021; Emery Thompson et al. 2020). These studies highlight the need for caution when making cross-species inferences, as similarities in aging processes across species, such as humans and chimpanzees, do not necessarily correspond to similar functional outcomes (e.g., musculoskeletal aging may differ based on species’ physical demands).

With increased human longevity comes a delayed age at first birth (AFR) relative to great apes (Konner 2017). This delay is relatively constant even in post-agricultural societies, according to historical records (Le Bourg et al. 1993; Pettay et al. 2005). In nomadic foragers with natural fertility, the average AFR is about 19 years, while AFR in great apes ranges from 10 years in gorillas to 15 years in orangutans (Emery Thompson and Sabbi 2019). Similarly, human gestation is 10 to 30 days longer than in other great apes, which correlates with the larger infant size at birth (Emery Thompson and Sabbi 2019).

While AFR and gestation duration align with the increase in body mass and longevity, a derived aspect of human life history that contradicts these trends is the relatively short interbirth interval (IBI). In human hunter-gatherers, the mean IBI is 3.7 years, and the average age at weaning is approximately 2.5 years (Konner 2017; Mace 2000; Robson et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2006). In comparison, chimpanzees and orangutans have IBIs that are roughly twice as long: 4.5 years for chimpanzees, 7 years for orangutans (Robson et al. 2006). This is remarkable because, in all other aspects, human life history has slowed relative to the presumed ancestral (ape-like) state. Thus, human life history cannot be reduced to a simple shift, comparing to great apes, towards the K-end of the r/K spectrum (MacArthur and Wilson 1967).

Another unique life history trait of humans, shared with only a few non-terrestrial mammals, is the presence of a significant post-reproductive lifespan (PRLS) (Ellis et al. 2018). Theoretical work over the past 50 years has provided a framework for understanding senescence (the gradual deterioration of functional characteristics) in general, but it remains difficult to explain the decoupling of somatic and reproductive senescence (Kirkwood and Shanley 2010). Typically, somatic and reproductive senescence are linked: maintaining a functional germline is unlikely to be advantageous if somatic decline hinders the production of fertile offspring (Jones et al. 2014). However, in a few species, the two processes are decoupled—either somatic senescence is delayed or reproductive senescence is accelerated. This results in an extended PRLS, which has evolved independently at least three times in mammals, including primates (Ellis et al. 2018). In humans, the most plausible explanation for the evolution of a significant PRLS is the delay of somatic senescence, with reproductive decline proceeding at a constant rate, as it occurs at a similar age than in chimpanzees (Wood et al. 2023). Given the limited comparative sample, phylogenetically informed studies of the evolution and adaptive significance of PRLS are challenging. Some argue that PRLS is an adaptive trait (Brent et al. 2015; Cant and Johnstone 2008; Hawkes et al. 1998; Lahdenperä et al. 2004), while others consider it either widespread across species (Austad 1997; Cohen 2004; Tully and Lambert 2011) or unique to humans but consistent with life history allometries (Judge and Carey 2000).

Finally, many researchers (Bogin 1997; Konner 2017; Leigh 2001) contend that childhood is a distinct and unique ontogenetic phase in humans. In other primates, newborns transition from infants to juveniles when weaning is complete, meaning that nutritional independence coincides with the end of nursing (Pereira and Leigh 2003). In contrast, human children are weaned before they achieve the anatomical traits (e.g., mature dentition and full motor dexterity) that would allow them to become nutritionally independent. Childhood, therefore, is the period between the end of infancy (~2.5 years) and the beginning of the juvenile stage, during which children are still nutritionally dependent on other group members.

In summary, humans exhibit derived life history traits that deviate from the great ape trend: some traits have slowed down (prolonged lifespan, delayed AFR), others have accelerated (shortened IBI), and still others are entirely novel (childhood and PRLS). While there is consensus about the emergence of modern human skeletal anatomy in Africa (Hublin et al. 2017) and the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa in the late Pleistocene (Harvati et al. 2019), the evolution of the human life history strategy remains an intriguing puzzle that has yet to be fully understood. Our current limited data restricts our ability to test the various hypotheses surrounding this evolution. The following sections will focus explicitly on our current understanding of growth, development, reproduction, and lifespan in fossil hominins.

Hominin life history

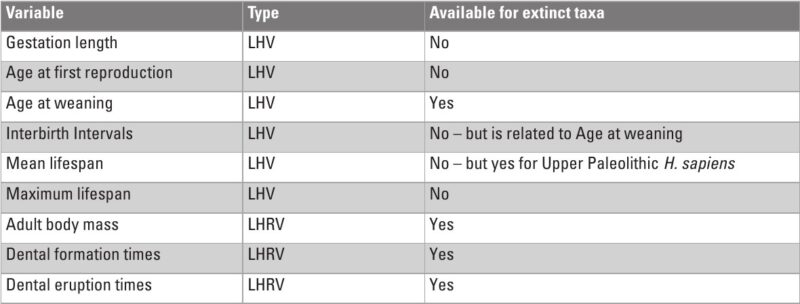

Until now, attempts to understand hominin life history have primarily relied on comparisons between living species, by leveraging phylogenetically conserved relationships between the timing of some life history events (e.g. weaning, AFR) and the value of other variables that can more easily be inferred in the hominin fossil record (e.g., body mass, brain mass, dental eruption times). However, recent advances in methodology offer the potential to reconstruct the changes that occurred during human evolution, allowing us to better understand which traits evolved together, and the timing and potential selective pressures behind their emergence. Following Robson and Wood (2008), a distinction is made between two types of variables (Table 1) that are often confused: life history variables (LHVs) and life history related variables (LHRVs).

Longevity

The accuracy of estimating chronological age from hard tissues (bones and teeth) declines significantly once growth is complete. This is because most methods of skeletal aging rely on assessing the degree of formation of structures, such as dental development or cranial suture obliteration (Martrille et al. 2007), where the timing of these processes is well characterized in modern populations. In contrast, aging adults is based on degenerative processes, such as dental wear, which have much more interindividual variation than developmental processes (McFadden et al. 2019). Evidence suggests that the pace of development in extinct hominins differed from that of modern humans (Bromage and Dean 1985; Dean et al. 2001). Thus, while anatomical developmental milestones can indicate a particular ontogenetic phase, they do not provide a precise estimate of the chronological age at which these milestones are reached.

Current hypotheses on the evolution of human longevity are based on the assumption that body and brain mass are closely linked to lifespan (Robson and Wood 2008; Schwartz 2012). Regressions linking lifespan and body mass in extant primates (Judge and Carey 2000) suggest a significant increase in longevity between Homo habilis (52-56 years) and H. erectus (60-63 years) around 1.7 to 2 million years ago (Lieberman et al. 2021; Tobias 2006), coinciding with a rapid increase in brain size (Gómez-Robles et al. 2017). However, caution is needed when accepting values inferred from these regressions, as modern humans deviate from such patterns. A demographic approach to understanding longevity, focused on age-structure pyramids (with just two age categories: young and old), based on dental wear in four broadly-defined hominin groups (australopithecines, Early Homo, Neanderthals, and Upper Paleolithic humans), suggests that old age only became relatively common in human evolution around 50,000 years ago, particularly among Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens (Caspari and Lee 2004). This finding supports previous research on Neanderthal mortality patterns (Trinkaus 1995).

Ontogeny

Our current understanding of hominin life history largely depends on patterns of growth and development. Research on this topic falls into two main categories: studies based on known correlations between dental development and the achievement of ontogenetic milestones (e.g., first molar emergence and weaning) (T. M. Smith 2013), which provide relative data, and studies using histological methods, which offer absolute chronological values (reviewed in: Dean 2006).

Several studies examining the correlation between molar emergence and life history variables have been conducted since Adolph Schultz’s pioneering work in (Schultz 1949). These studies typically focus on extant humans and great apes (Jeanson et al. 2016; B. H. Smith 1984, 1989; B. H. Smith et al. 1994), so the regressions derived from them are not directly applicable to extinct hominins. Indeed, early radiographic studies and more recent virtual histological analyses have demonstrated that the dental ontogeny of early hominins—such as Paranthropus, Australopithecus (Bromage 1987; T. M. Smith et al. 2015), early Homo (T. M. Smith et al. 2015), H. erectus (Dean 2016; Zollikofer et al. 2024), and Neanderthals (T. M. Smith, Tafforeau, et al. 2010) — was distinct, and not simply intermediate between modern apes and humans.

With the introduction of histological methods in dental anthropology, researchers can now assign an absolute chronology to dental ontogeny in individual fossil specimens. This approach reduces the uncertainty associated with inferences drawn from comparative datasets. Since Bromage and Dean’s foundational work in 1985, studies on hominin growth and development have rapidly proliferated. Based on dental development, we now know that the maturation rate in Paranthropus (Dean et al. 2020), Australopithecus, and H. erectus was faster than in modern humans (Dean et al. 2001; Dean and Smith 2009; Zollikofer et al. 2024). Specifically, the age at first molar emergence is estimated to be about 3 years in Paranthropus boisei, 3.2 years in Australopithecus africanus (Kelley and Schwartz 2012), and 4.5 years in Homo erectus (Dean et al. 2001), while in modern humans it is about 6 years. Ontogenetic studies of cranial morphology ontogeny (Antón and Leigh 2003) suggest that H. erectus lacked a clear adolescent growth spurt, a hallmark of modern human development. However, the significant morphological variation within H. erectus, despite its large geographic and temporal spread, is seen as indicative of developmental plasticity—greater than that of Neanderthals but still not as advanced as in modern humans (Antón et al. 2016).

Recent research on ontogenetic patterns has predominantly focused on Neanderthals (Dean et al. 1986; Guatelli‐Steinberg 2009; Hogg et al. 2020; Macchiarelli et al. 2006; Mahoney et al. 2021; McGrath et al. 2021; Nava et al. 2020; Rozzi and De Castro 2004; T. M. Smith et al. 2007, 2018; T. M. Smith, Tafforeau, et al. 2010). These studies collectively suggest that Neanderthal ontogeny was faster than that of modern humans. In summary, no extinct hominin species exhibits growth patterns similar to those of modern humans. The earliest evidence of modern human life history is found in a specimen of H. sapiens from around 300,000 years ago at Jebel Irhoud, Morocco (T. M. Smith et al. 2007), which also represents one of the earliest known sites of H. sapiens.

Age at weaning

The earliest hominin species for which we have evidence regarding the age of weaning is Australopithecus africanus. Recent work suggests that, in at least one individual, the transition away from a predominantly maternal-milk diet occurred at around one year of age (Joannes-Boyau et al. 2019). After this point, cyclical patterns of elemental composition are observed in the dental enamel, likely reflecting irregular food availability. This supports the long-standing hypothesis that, over the course of hominin evolution, there has been a trend toward an earlier weaning age, with modern humans weaning earlier than extant Pan species. In wild chimpanzees, for example, while there is variation within the species, a significant increase in solid food intake typically begins at around one year of age (Lonsdorf et al. 2020).

Direct evidence for weaning age is also available for Neanderthals. Estimates of the onset of weaning vary, with different studies suggesting ages of approximately 9 months (T. M. Smith et al. 2018), 7 months (Austin et al. 2013), and 6 months (Nava et al. 2020). In modern humans, the typical age of solid food introduction is around 6 months, with ranges in hunter-gatherer populations being 5.0+/4.0 months (Sellen 2001). Collectively, these studies suggest that while there was variability within species, Neanderthals were weaned at a similar age to modern humans. Even if Neanderthals had a slightly later age at weaning than modern humans (T. M. Smith, Tafforeau, et al. 2010), it appears that a human-like age at weaning either evolved before the divergence of humans and Neanderthals or developed independently in both lineages, with the former scenario being the more likely and parsimonious explanation.

Reproduction, menopause and other open questions

While some direct evidence exists for the timing of early life history milestones in extinct hominins, much less is known about milestones occurring later in life. Until recently, methods for studying interbirth intervals (IBIs) and post-reproductive lifespan (PRLS) in fossil specimens have been unavailable. Although a minimum IBI can be deduced from the age at weaning, determining the upper limit or typical value remains elusive and may depend on factors like allomaternal support, especially in cooperatively breeding species such as humans and marmosets (Brügger and Burkart 2021; Hrdy 2009).

This scarcity of data poses challenges for addressing several key questions: I) When did a post-reproductive lifespan first evolve?; II) did the emergence of PRLS align with reduced IBIs, as proposed by the grandmother hypothesis (Hawkes et al. 1998)?; III) or did changes in IBIs coincide with the development of a cooperative breeding system (Burkart et al. 2009), akin to that of callitrichids, where older siblings rather than grandparents provide care?

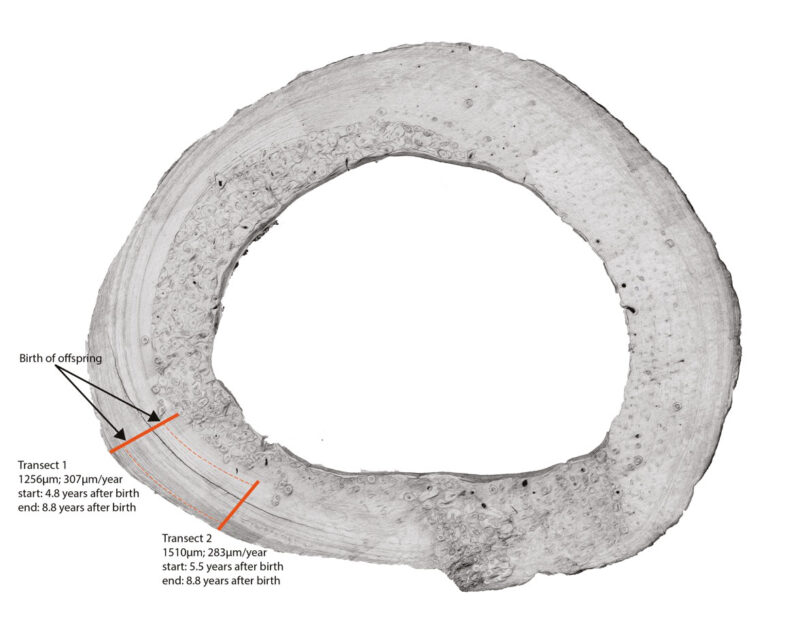

Currently, evidence on these topics is limited. The earliest signs of older-age individuals (and potentially grandmothering) are found in Upper Paleolithic Homo sapiens (Caspari and Lee 2004), with possible reproductive events detected through the analysis of cementum in Neanderthal fossils from Krapina, Croatia (120 kya) (Cerrito, Nava, et al. 2022).

To summarize, certain elements of recent human life history align with a “live slow” strategy, while others suggest a “live fast” approach. A central question in hominin life history research is whether the modern human life history profile evolved as a single, unified framework or through a mosaic process involving staggered shifts in timing across hominin evolution. Among the most derived features of human life history are shortened IBIs and extended PRLSs (Hawkes et al. 1998). However, it remains unclear if these traits evolved simultaneously. Notably, humans are unique among primates in decoupling the age at weaning from the eruption of the first permanent molar (Robson et al. 2006). Some researchers propose that prolonged infant reliance on adult-provided food may be connected to a cooperative breeding system (Hawkes et al. 1998; Hrdy 2009; Kramer 2010; Kramer and Otárola-Castillo 2015; van Schaik and Burkart 2010). To further investigate the relationship between cooperative breeding and grandmothering (as distinct from other forms of alloparenting) (Hawkes et al. 1998), it is crucial to examine the frequency of female reproductive output and the duration of the female post-reproductive phase.

The next section examines the analytical methods that can help infer the frequency of female reproductive events and estimate the age of menopause. These approaches may provide valuable insights into unresolved questions about the evolutionary trajectory of human life history.

The skeleton as a dynamic organ

In mammals, skeletal physiology is implicated in energy metabolism, endocrine regulation, and overall mineral homeostasis (DiGirolamo et al. 2012). As a result, it both reflects and influences internal metabolic rhythms (Bromage, Idaghdour, et al. 2016) and responds to environmental cycles (Doherty et al. 2015). Furthermore, skeletal physiology responds to, and plays a role in, various physiologically significant events (Carrel 1994; Dirks et al. 2002; Lemmers et al. 2021) and adapts to changes in the environment (Bromage et al. 2011; Cipriano 2002; Hamilton et al. 2021). Since the present article addresses the timing of life history events, I will focus on how the skeleton tracks internal metabolic changes, but I will not review how it responds to external (e.g., environmental, climatic) ones.

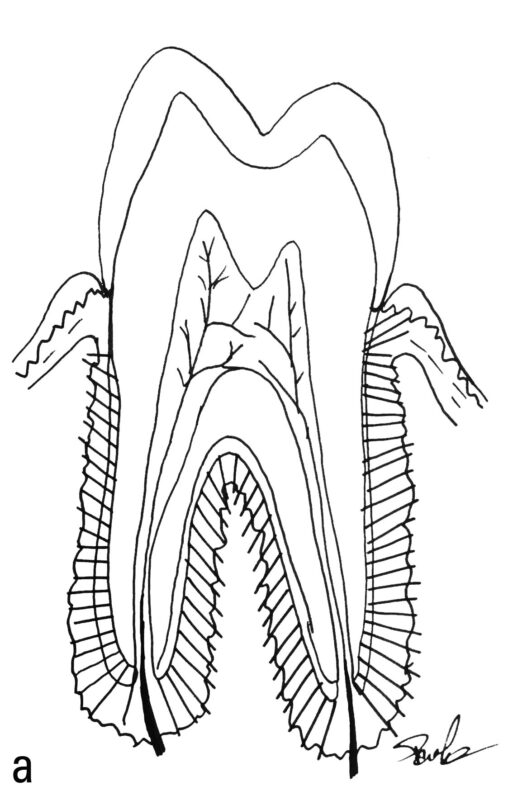

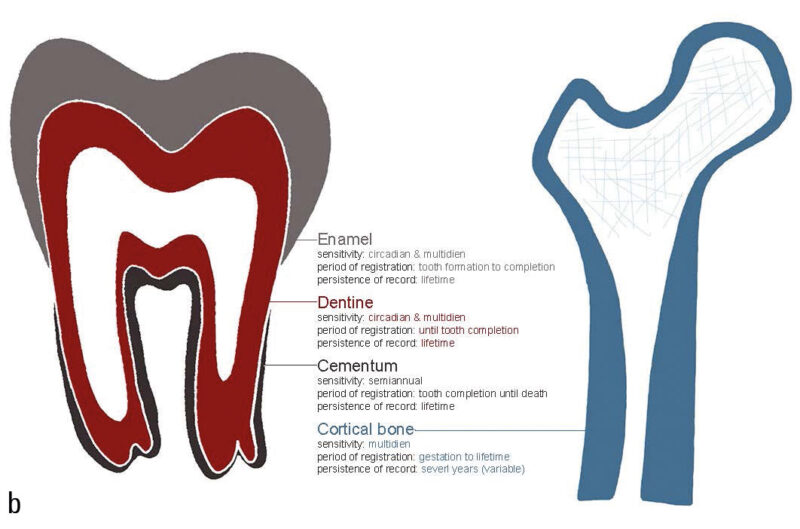

Much of what we know about the timing of life history variables (LHVs) in fossil specimens comes from histomorphological or elemental analyses of teeth, which serve as recording structures. Recording structures (Klevezal 1995) include a variety of animal tissues, such as mollusk shells, scales, otoliths, dental cementum (Fig. 1), bone (Fig. 2), enamel, dentine, claws, nails, horns, and even ear plugs (Trumble et al. 2018). These structures are periodically layered, with each layer being deposited in sequence, and are often referred to as “growth layers.” The layers reflect changes in micromorphology that correspond to shifts in the organism’s physiological state. Different tissues have distinct layer characteristics. For instance, cementum and dentine show bands of varying transparency, while horns exhibit alternating ridges and grooves.

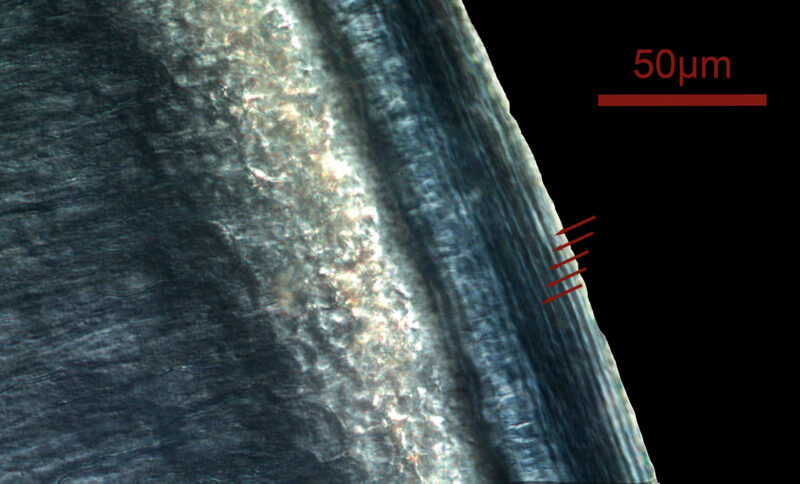

Recording structures can be categorized based on three parameters (Klevezal 1995): sensitivity, which refers to how frequently new layers are added; the period of registration (the time frame during which the structure records); and the persistence of the record (how long the structure retains the recorded layers unchanged). The sensitivity of a structure depends on both its structural complexity (Ryan et al. 2020) and its growth rate. For example, in humans, the recording unit in bone is the lamella, while in enamel, the corresponding unit includes multiple smaller increments known as cross-striations (Hogg 2018). This means that for the same time period, enamel has approximately 8 layers, whereas bone has only one. The mean thickness of a lamella in a human Haversian system is 9.0 ± 2.13 μm (Pazzaglia et al. 2012), while the thickness of a daily cross-striation in enamel is 2.7 ± 0.43 μm (Desoutter et al. 2019). As a result, the same time period is recorded in approximately 9 μm of bone and 20 μm of enamel, making enamel more sensitive than bone. This difference is important when conducting analyses that require high temporal precision, especially when the spatial detection limit of certain instruments (e.g., optical microscopy or laser-ablation mass spectrometry) is considered.

The period of registration refers to the time during which a structure continues to add new layers. In humans, enamel layers stop forming once the tooth crown is fully developed, while bone continues to deposit new layers throughout the individual’s life. The persistence of the record is influenced by the turnover rate of the tissue. Enamel does not undergo turnover, while instead bone is resorbed and newly formed in response to both mechanical and physiological demands. This remodeling can cause significant variability in the persistence of the record, even within different bones of the same individual (Fahy et al. 2017). When bone tissue is resorbed, the record contained within it is lost.

In primates, the primary recording structures are bone, dentine, cementum, and enamel. Figure 3 summarizes the temporal characteristics of these four structures. As can be seen in this table, the only two tissues that continue formation throughout an individual’s lifetime, and therefore the only two that are capable of recording adult life history events, are cementum and bone. Bone has a higher sensitivity, with a lamella having a period of about eight days in humans (Bromage et al. 2009). However, given its turnover (resorption and new formation) during life, the persistence of the record is limited to some years, making it difficult to derive chronologies for an individual (Fig. 2). On the other hand, cementum has a much lower sensitivity, with a pair of dark and light annuli formed each year (Fig. 1), but it does not undergo remodeling and therefore the record persists unaltered until death.

Internal environment: metabolism – mediated development

Metabolism in organisms encompasses all chemical processes involved in transforming food into energy (e.g., adenosine triphosphate) and structural molecules (e.g., proteins and nucleic acids), as well as eliminating the waste products generated during these transformations. The rate of metabolic processes, or the “pace of life” (the amount of energy or matter converted per unit of time), is governed by three main periodicities: I) the circadian rhythm, which is highly conserved across species, II) an annual cycle influenced by environmental factors, and III) a multidien internal rhythm linked to body mass, which nonetheless includes a phylogenetic component. These periodicities regulate the formation of layered structures in hard tissues, forming the basis for estimating age at death and chronologically reconstructing physiologically impactful events, visible as subtle histological changes in these periodic increments.

The circadian rhythm is evident in the daily cross-striations of enamel, resulting from the circadian transcription factors regulating matrix secretion in ameloblasts, the enamel-forming cells (Lacruz et al. 2012).

A much longer cycle, the annual rhythm, also modulates metabolism. This cycle is driven by seasonal variations in sunlight (Gorman et al. 2019) and temperature (Seebacher 2009). These changes manifest as yearly growth lines in hard tissues (Foster and Hujoel 2018). Osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), and likely cementoblasts (cementum-forming cells) due to their similarity, regulate insulin production and adipose tissue metabolism, integrating their high energy demands into the body’s overall energy balance, which is affected by thermoregulation (Dirckx et al. 2019; Seebacher 2009).

The multidien rhythm, known as the Havers-Halberg Oscillation (HHO), modulates metabolic activities that influence variations in the pace of life. This rhythm was first identified in enamel, as accentuated lines with taxon-specific variability. In humans, the HHO cycle averages 8-9 days (Bromage et al. 2009). Research shows that this periodicity correlates with body mass and tissue-specific metabolic rates, with smaller mammals exhibiting faster metabolic rates and higher HHO frequencies compared to larger mammals (Bromage, Idaghdour, et al. 2016; Karaaslan et al. 2020; MacAvoy et al. 2006). In bone, HHO periodicity influences the density and size of osteocyte lacunae (a small space in the bone containing the osteocyte), with larger individuals displaying increased density and size (Bromage, Juwayeyi, et al. 2016). Furthermore, HHO periodicity governs lamellar increments in hard tissues, with each lamella corresponding to one Retzius periodicity (RP). In dentine and enamel, the number of daily cross-striations between two RPs is used to calculate the RP interval, which reflects the HHO periodicity.

Adult age estimation

Since the enamel of deciduous teeth begins forming during prenatal development, a Retzius periodicity (RP) increment corresponding to birth is observed. This increment is both histologically accentuated (Weber and Eisenmann 1971) and elementally distinct (reviewed in: Nava et al. 2024). Known as the neonatal line, it provides a clear reference point (birth) from which all subsequent (and prior) increments can be assigned chronological values. Due to the staggered development of different tooth classes, increments in earlier-forming teeth can be matched to those in later-forming teeth, enabling the construction of chronologies that cover the formation times of multiple teeth (e.g., Zollikofer et al. 2024). This approach, which leverages circadian and multidien periodicities, has been applied to estimate the age at death of immature hominin fossil remains (Bromage and Dean 1985; Lacruz et al. 2005; T. M. Smith, Tafforeau, et al. 2010).

For adult individuals, age at death can be estimated using the yearly periodicity of cementum deposition. However, this method is less precise due to the absence of a neonatal line and the need to make assumptions about the age at which cementoblast secretion begins (typically corresponding to gingival emergence). Accurate estimation requires prior knowledge of dental development timelines. Such data is available for many extant primates (AlQahtani et al. 2010; Bolter and Zihlman 2011; Kralick et al. 2017; Liversidge 2008; T. M. Smith 2016; T. M. Smith, Smith, et al. 2010; Trotter et al. 1977; Zihlman et al. 2004) but is more challenging to establish for extinct species.

Despite these challenges, cementum annulations have been widely used to estimate age at death across various mammals (Fig. 1). Examples include rhesus macaques (Kay et al. 1984; Kay and Cant 1988), horses (Prilepskaya et al. 2020), several cervid species (Takken Beijersbergen 2019; Veiberg et al. 2020), bears (Christensen-Dalsgaard et al. 2010), bats (Cool et al. 1994), extinct stem mammals (Newham, Gill, et al. 2020), Jurassic fossil specimen (Panciroli et al. 2024), extinct hominins (Cerrito, Nava, et al. 2022; van Heteren et al. 2023), as well as contemporary (Sultana et al. 2021; Wittwer‐Backofen et al. 2004) and archaeological humans (Großkopf 1990; Huffman and Antoine 2010; Le Cabec et al. 2019; Tanner et al. 2021).

Internal environment: maintenance of homeostasis with changing physiology

During significant physiological events such as birth, weaning, or menopause, organisms must adjust to maintain homeostasis (Gross 1998) while efficiently managing energy availability. Given the systemic complexity of organisms, these homeostatic adaptations involve multiple systems and organs. Consequently, changes in reproductive physiology and nutrition are closely linked to skeletal alterations.

The skeleton and the endocrine system are interconnected through several proximate mechanisms, to the extent that the skeleton is sometimes described as an endocrine organ (DiGirolamo et al. 2012; Fukumoto and Martin 2009; Guntur and Rosen 2012). Acting as the largest reservoir of calcium and phosphate, bone plays a key role in regulating the balance of these elements. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and vitamin D elevate serum calcium and phosphate levels by promoting bone resorption and enhancing intestinal absorption, whereas FGF23, a hormone produced by bone, reduces these concentrations (Bergwitz and Jüppner 2010). Bone is also involved in energy and feeding regulation through a hypothalamic-osteoblastic-endocrine loop. In this loop, leptin signals osteoclasts to suppress bone formation and increase resorption (Ducy et al. 2000). Conversely, osteocalcin, a protein specific to bone and cementum and expressed by osteocytes, osteoblasts, and cementocytes (Kagayama et al. 1997), increases insulin secretion (Lee et al. 2007) and stimulates testosterone production (Karsenty and Oury 2014).

Cementum (Silk et al. 2008) and bone (Cauley 2015; Gillies 2017) are both highly responsive to estrogen levels. Estrogen facilitates calcium storage in preparation for reproductive events, while declining estrogen levels—such as during menopause—lead to increased osteoclastic activity and a net loss of bone tissue (Ahlborg et al. 2003). These effects occur across females of various ethnic groups (Finkelstein et al. 2008) and are associated with changes in hydroxyapatite (HA) crystal size and orientation (Burnell et al. 1982; Turunen et al. 2016) as well as cortical bone porosity and mineralization (Sharma et al. 2018).

Other reproductive hormones, such as prolactin (PRL) and oxytocin (OT), also influence the skeleton. PRL receptors are expressed in osteoblasts, and mice lacking these receptors exhibit reduced bone mass due to increased turnover and net bone loss (Clément-Lacroix et al. 1999; Seriwatanachai et al. 2008). OT supports bone (Colaianni et al. 2012) and cementum (Colaianni et al. 2012) by promoting cell proliferation, migration, and differentiation, leading to tissue growth. This aligns with OT’s reproductive role and the substantial transfer of calcium and phosphorus from mothers to offspring during lactation, necessitating rapid bone mass recovery post-lactation (Kovacs 2016).

Unsurprisingly, elemental and histological changes in bone and cementum have been associated with life history events like reproduction (Carrel 1994; Cerrito et al. 2020, 2021, 2023; Cerrito, Nava, et al. 2022; Medill et al. 2010; Von Biela et al. 2008; Wittwer‐Backofen et al. 2004). Mineral and hormonal fluctuations are recorded in mineralized tissues, preserving these changes during tissue formation.

Zinc concentrations in cementum have been shown to reflect the onset of sexual maturity in walruses (Clark et al. 2020), while declining fertility correlates with increased copper levels in rat teeth (Rahnama 2002). Moreover, lead and cobalt levels in human dentine exhibit sexual dimorphism (Kumagai et al. 2012), as do the relative concentrations of elements in macaque cementum (Cerrito et al. 2023).

Histological changes in cementum linked to reproductive events have been observed in several species, including bears (Carrel 1994; Coy and Garshelis 1992), sea otters (Von Biela et al. 2008), humans (Cerrito et al. 2020; Cerrito, Nava, et al. 2022), and macaques (Cerrito et al. 2021, 2023). Similarly, dentine displays accentuated lines associated with human parturitions (Dean and Elamin 2014). Table 2 summarizes life history variables recoverable from hard tissues, alongside the tissue types, methodologies, and relevant references.

A few studies have demonstrated the potential to recover hormonal concentrations preserved within human dental tissues (Nejad et al. 2016; Quade et al. 2021, 2023) and those of other marine mammals (Hudson et al. 2021).

Conclusion

The combined literature reviewed here indicates that: 1) cementum reliably records adult physiological stressors in humans and non-human primates; 2) that such information can be recovered non-destructively; and 3) that the method can be applied to the hominin fossil record. Furthermore, recent work on non-human mammals (Cerrito et al. 2023; Clark et al. 2020) provides a methodological framework to overcome a long-standing caveat of histological research applied to life-history studies, by showing that changes in reproductive physiology (onset of menarche, reproduction) can be recovered and timed via the analysis of element concentrations in cementum. Furthermore, the combined evidence of elemental analysis of both cementum (Cerrito et al. 2023) and bone (Cerrito, Hu, et al., 2022) in the same individuals provides evidence for the potential of using a systemic approach when investigating single fossil elements since the same elemental signal is recoverable in different tissues of the same skeleton.

Indeed, there is a rapidly increasing field of research (Dean et al. 2018; Le Cabec et al. 2019; Newham, Corfe, et al. 2020) that identifies dental cementum as a tissue with great potential to expand our current knowledge regarding hominin life history evolution. By constituting a biological archive of the entirety of an individual’s life, dental cementum should permit the investigation of our peculiar reproductive strategy.

However, several caveats remain, indicating possible directions for future research. First, while fossils require non-destructive analytical approaches, event identification requires elemental analysis. Nonetheless, several fossil specimens present naturally broken dental roots, thus exposing the cementum in its entire thickness and allowing for its analysis using synchrotron X-ray fluorescence mapping (Dean et al. 2018). This method may be used to recover the reproductive histories, and specifically interbirth intervals, in extinct hominin species for which we have dental specimens with broken roots.

Non-destructive histological methods are limited by their lower resolution (compared to real histology), which increases the error of age estimates. While this problem has limited impact on the study of the evolution of menopause, it is particularly relevant if attempting to investigate the evolution of interbirth-intervals (IBIs). The use of higher-energy beams, allowing for smaller voxel sizes (higher resolutions), could partially resolve this problem.

In addition to exploring the histology and elemental composition of hard tissues to extrapolate physiological information, it is likely that endocrine changes are also recorded in hard tissues and can be used to reconstruct life-history scheduling. Recent research has reported the possibility of recovering hormonal concentrations embedded in the dental tissues of humans (Nejad et al. 2016; Quade et al. 2021, 2023) and other marine mammals (Hudson et al. 2021). The study by Hudson and colleagues is particularly promising for human life history research, because it detects differing concentrations of progesterone and testosterone for individuals of different age classes and reproductive phases. Although their method currently lacks the spatial resolution to detect temporal changes, it effectively identifies variations in progesterone and testosterone levels across individuals of different age groups and reproductive stages. This technique could potentially be applied to determine whether a female has undergone menopause or not.

In sum, several methodological advances of the recent years will likely allow for actual data on when, where and in association with which morphological and environmental conditions a post-reproductive lifespan evolved. A more difficult investigation, because of the high level of resolution necessary, will be the evolution of shortened IBIs – since a difference of as little as one year has profound implications on our understanding of how such an energetically costly adaptation evolved. Advances capable of providing actual data to support or disprove current evolutionary hypotheses are necessary in order to understand the extent to which our cultural adaptations have shaped our physiological and biological ones, with concurrent downstream effect and feedback loops with our cognitive characteristics.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply thankful to Susan Antón, Shara Bailey, Tim Bromage, James Higham and Carel van Schaik for their helpful suggestions and comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

AlQahtani, S. J., Hector, M. P., and Liversidge, H. M. 2010: Brief communication: the London atlas of human tooth development and eruption. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 142(3), 481–490.

Antón, S. C. and Leigh, S. R. 2003: Growth and life history in Homo erectus. Cambridge Studies in Biological and Evolutionary Anthropology, 219–245.

Antón, S. C., Taboada, H. G., Middleton, E. R., Rainwater, C. W., Taylor, A. B., Turner, T. R., Turnquist, J. E., Weinstein, K. J., and Williams, S. A. 2016: Morphological variation in Homo erectus and the origins of developmental plasticity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371(1698), 20150236.

Austad, S. N. 1997: Postreproductive survival. Between Zeus and the Salmon 60(21), 161.

Austin, C., Smith, T. M., Bradman, A., Hinde, K., Joannes-Boyau, R., Bishop, D., Hare, D. J., Doble, P., Eskenazi, B., and Arora, M. 2013: Barium distributions in teeth reveal early-life dietary transitions in primates. Nature 498(7453), 216–219, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12169.

Bergwitz, C. and Jüppner, H. 2010: Regulation of phosphate homeostasis by PTH, vitamin D, and FGF23. Annual Review of Medicine 61, 91–104.

Bogin, B. 1997: Evolutionary hypotheses for human childhood. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists 104(S25), 63–89.

Bolter, D. R. and Zihlman, A. L. 2011: Brief communication: dental development timing in captive Pan paniscus with comparisons to Pan troglodytes. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 145(4), 647–652.

Brent, L. J., Franks, D. W., Foster, E. A., Balcomb, K. C., Cant, M. A., and Croft, D. P. 2015: Ecological knowledge, leadership, and the evolution of menopause in killer whales. Current Biology 25(6), 746–750.

Bribiescas, R. G. 2020: Aging, life history, and human evolution. Annual Review of Anthropology 49, 101–121.

Bromage, T. G. 1987: The biological and chronological maturation of early hominids. Journal of Human Evolution 16(3), 257–272.

Bromage, T. G. and Dean, M. C. 1985: Re-evaluation of the age at death of immature fossil hominids. Nature 317(6037), 525–527.

Bromage, T. G., Idaghdour, Y., Lacruz, R. S., Crenshaw, T. D., Ovsiy, O., Rotter, B., Hoffmeier, K., and Schrenk, F. 2016: The swine plasma metabolome chronicles “many days” biological timing and functions linked to growth. PLoS One 11(1), e0145919.

Bromage, T. G., Juwayeyi, Y. M., Katris, J. A., Gomez, S., Ovsiy, O., Goldstein, J., Janal, M. N., Hu, B., and Schrenk, F. 2016: The scaling of human osteocyte lacuna density with body size and metabolism. Comptes Rendus Palevol 15(1–2), 32–39.

Bromage, T. G., Juwayeyi, Y. M., Smolyar, I., Hu, B., Gomez, S., and Chisi, J. 2011: Enamel-calibrated lamellar bone reveals long period growth rate variability in humans. Cells Tissues Organs 194(2–4), 124–130.

Bromage, T. G., Lacruz, R. S., Hogg, R., Goldman, H. M., McFarlin, S. C., Warshaw, J., Dirks, W., Perez-Ochoa, A., Smolyar, I., and Enlow, D. H. 2009: Lamellar bone is an incremental tissue reconciling enamel rhythms, body size, and organismal life history. Calcified Tissue International 84(5), 388–404.

Brügger, R. K. and Burkart, J. M. 2021: Parental reactions to a dying marmoset infant: conditional investment by the mother, but not the father. Behaviour 159(1), 89–109.

Burkart, J. M., Hrdy, S. B., and van Schaik, C. P. 2009: Cooperative breeding and human cognitive evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 18(5), 175–186.

Burnell, J. M., Baylink, D. J., Chestnut III, C. H., Mathews, M. W., and Teubner, E. J. 1982: Bone matrix and mineral abnormalities in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Metabolism 31(11), 1113–1120.

Cant, M. A. and Johnstone, R. A. 2008: Reproductive conflict and the separation of reproductive generations in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105(14), 5332–5336.

Carey, J. R. and Judge, D. S. 2001: Life span extension in humans Is self-reinforcing: a general theory of longevity. Population and Development Review 27(3), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2001.00411.x.

Carrel, W. K. 1994: Reproductive history of female black bears from dental cementum. Bears: Their Biology and Management, 205–212.

Caspari, R. and Lee, S.-H. 2004: Older age becomes common late in human evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101(30), 10895–10900.

Cauley, J. A. 2015: Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids 99, 11–15.

Cerrito, P., Bailey, S. E., Hu, B., and Bromage, T. G. 2020: Parturitions, menopause and other physiological stressors are recorded in dental cementum microstructure. Scientific Reports 10(1), 1–10.

Cerrito, P., Cerrito, L., Hu, B., Bailey, S. E., Kalisher, R., and Bromage, T. G. 2021: Weaning, parturitions and illnesses are recorded in rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) dental cementum microstructure. American Journal of Primatology 83(3), e23235.

Cerrito, P., Hu, B., Goldstein, J. Z., Kalisher, R., Bailey, S. E., and Bromage, T. G. 2022: Elemental composition of primary lamellar bone differs between parous and nulliparous rhesus macaque females. Plos One 17(11), e0276866.

Cerrito, P., Hu, B., Kalisher, R., Bailey, S. E., and Bromage, T. G. 2023: Life history in primate teeth is revealed by changes in major and minor element concentrations measured via field-emission SEM-EDS analysis. Biology Letters 19(1), 20220438. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2022.0438.

Cerrito, P., Nava, A., Radovčić, D., Borić, D., Cerrito, L., Basdeo, T., Ruggiero, G., Frayer, D. W., Kao, A. P., Bondioli, L., and Bromage, T. G. 2022: Dental cementum virtual histology of Neanderthal teeth from Krapina (Croatia, 130-120 kyr): an informed estimate of age, sex and adult stressors. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 19(187), 20210820.

Christensen-Dalsgaard, S. N., Aars, J., Andersen, M., Lockyer, C., and Yoccoz, N. G. 2010: Accuracy and precision in estimation of age of Norwegian Arctic polar bears (Ursus maritimus) using dental cementum layers from known-age individuals. Polar Biology 33(5), 589–597.

Cipriano, A. 2002: Cold stress in captive great apes recorded in incremental lines of dental cementum. Folia Primatologica 73(1), 21–31.

Clark, C. T., Horstmann, L., and Misarti, N. 2020: Zinc concentrations in teeth of female walruses reflect the onset of reproductive maturity. Conservation Physiology 8(1).

Clément-Lacroix, P., Ormandy, C., Lepescheux, L., Ammann, P., Damotte, D., Goffin, V., Bouchard, B., Amling, M., Gaillard-Kelly, M., and Binart, N. 1999: Osteoblasts are a new target for prolactin: analysis of bone formation in prolactin receptor knockout mice. Endocrinology 140(1), 96–105.

Cohen, A. A. 2004: Female post-reproductive lifespan: a general mammalian trait. Biological Reviews 79(4), 733–750.

Colaianni, G., Sun, L., Di Benedetto, A., Tamma, R., Zhu, L.-L., Cao, J., Grano, M., Yuen, T., Colucci, S., and Cuscito, C. 2012: Bone marrow oxytocin mediates the anabolic action of estrogen on the skeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry 287(34), 29159–29167.

Colchero, F., Aburto, J. M., Archie, E. A., Boesch, C., Breuer, T., Campos, F. A., Collins, A., Conde, D. A., Cords, M., and Crockford, C. 2021: The long lives of primates and the ‘invariant rate of ageing’ hypothesis. Nature Communications 12(1), 3666.

Cool, S. M., Bennet, M. B., and Romaniuk, K. 1994: Age estimation of pteropodid bats (Megachiroptera) from hard tissue parameters. Wildlife Research 21(3), 353–363.

Coy, P. L. and Garshelis, D. L. 1992: Reconstructing reproductive histories of black bears from the incremental layering in dental cementum. Canadian Journal of Zoology 70(11), 2150–2160.

Dean, M. C. 2006: Tooth microstructure tracks the pace of human life-history evolution. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273(1603), 2799–2808.

Dean, M. C. 2016: Measures of maturation in early fossil hominins: events at the first transition from australopiths to early Homo. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1698), 20150234, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0234.

Dean, M. C. and Elamin, F. 2014: Parturition lines in modern human wisdom tooth roots: do they exist, can they be characterized and are they useful for retrospective determination of age at first reproduction and/or inter-birth intervals? Annals of Human Biology 41(4), 358–367, https://doi.org/10.3109/03014460.2014.923047.

Dean, M. C., Le Cabec, A., Spiers, K., Zhang, Y., and Garrevoet, J. 2018: Incremental distribution of strontium and zinc in great ape and fossil hominin cementum using synchrotron X-ray fluorescence mapping. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 15(138), 20170626.

Dean, M. C., Leakey, M. G., Reid, D., Schrenk, F., Schwartz, G. T., Stringer, C., and Walker, A. 2001: Growth processes in teeth distinguish modern humans from Homo erectus and earlier hominins. Nature 414(6864), 628–631.

Dean, M. C. and Smith, B. H. 2009: Growth and development of the Nariokotome youth, KNM-WT 15000. In: F. E. Grine, J. G. Fleagle and R. E. Leakey (eds.), The first humans–origin and early evolution of the genus Homo. Springer, 101–120.

Dean, M. C., Stringer, C. B., and Bromage, T. G. 1986: Age at death of the Neanderthal child from Devil’s Tower, Gibraltar and the implications for studies of general growth and development in Neanderthals. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 70(3), 301–309.

Dean, M. C., Zanolli, C., Le Cabec, A., Tawane, M., Garrevoet, J., Mazurier, A., and Macchiarelli, R. 2020: Growth and development of the third permanent molar in Paranthropus robustus from Swartkrans, South Africa. Scientific Reports 10(1), 1–13.

Desoutter, A., Slimani, A., Al‐Obaidi, R., Barthélemi, S., Cuisinier, F., Tassery, H., and Salehi, H. 2019: Cross striation in human permanent and deciduous enamel measured with confocal Raman microscopy. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 50(4), 548–556.

DiGirolamo, D. J., Clemens, T. L., and Kousteni, S. 2012: The skeleton as an endocrine organ. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 8(11), 674.

Dirckx, N., Moorer, M. C., Clemens, T. L., and Riddle, R. C. 2019: The role of osteoblasts in energy homeostasis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 15(11), 651–665.

Dirks, W., Reid, D. J., Jolly, C. J., Phillips‐Conroy, J. E., and Brett, F. L. 2002: Out of the mouths of baboons: stress, life history, and dental development in the Awash National Park hybrid zone, Ethiopia. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists 118(3), 239–252.

Doherty, A. H., Ghalambor, C. K., and Donahue, S. W. 2015: Evolutionary physiology of bone: bone metabolism in changing environments. Physiology 30(1), 17–29.

Ducy, P., Amling, M., Takeda, S., Priemel, M., Schilling, A. F., Beil, F. T., Shen, J., Vinson, C., Rueger, J. M., and Karsenty, G. 2000: Leptin inhibits bone formation through a hypothalamic relay: a central control of bone mass. Cell 100(2), 197–207.

Ellis, S., Franks, D. W., Nattrass, S., Currie, T. E., Cant, M. A., Giles, D., Balcomb, K. C., and Croft, D. P. 2018: Analyses of ovarian activity reveal repeated evolution of post-reproductive lifespans in toothed whales. Scientific Reports 8(1), 1–10.

Emery Thompson, M., Rosati, A. G., and Snyder-Mackler, N. 2020: Insights from evolutionarily relevant models for human ageing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, The Royal Society, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0605.

Emery Thompson, M. and Sabbi, K. H. 2019: Evolutionary demography of the great apes. In: O. Burger, R. Lee, and R. Sear (eds.), Human Evolutionary Demography. Open Book Publishers, 423–474.

Fahy, G. E., Deter, C., Pitfield, R., Miszkiewicz, J. J., and Mahoney, P. 2017: Bone deep: variation in stable isotope ratios and histomorphometric measurements of bone remodelling within adult humans. Journal of Archaeological Science 87, 10–16.

Finkelstein, J. S., Brockwell, S. E., Mehta, V., Greendale, G. A., Sowers, M. R., Ettinger, B., Lo, J. C., Johnston, J. M., Cauley, J. A., and Danielson, M. E. 2008: Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 93(3), 861–868.

Foster, B. L. and Hujoel, P. P. 2018: Vitamin D in dentoalveolar and oral health. Vitamin D, 497–519.

Fukumoto, S. and Martin, T. J. 2009: Bone as an endocrine organ. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism 20(5), 230–236.

Gillies, B. 2017: Role of calcitriol in regulating maternal bone and mineral metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Master’s Thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Gómez-Robles, A., Smaers, J. B., Holloway, R. L., Polly, P. D., and Wood, B. A. 2017: Brain enlargement and dental reduction were not linked in hominin evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114(3), 468–473.

Gorman, S., de Courten, B., and Lucas, R. M. 2019: Systematic review of the effects of ultraviolet radiation on markers of metabolic dysfunction. The Clinical Biochemist Reviews 40(3), 147.

Gross, C. G. 1998: Claude Bernard and the constancy of the internal environment. The Neuroscientist 4(5), 380–385.

Großkopf, B. 1990: Individual age determination using growth rings in the cementum of buried human teeth. Zeitschrift Fur Rechtsmedizin. Journal of Legal Medicine 103(5), 351–359.

Guatelli‐Steinberg, D. 2009: Recent studies of dental development in Neandertals: implications for Neandertal life histories. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 18(1), 9–20.

Guntur, A. R. and Rosen, C. J. 2012: Bone as an endocrine organ. Endocrine Practice 18(5), 758–762.

Gurven, M. and Kaplan, H. 2007: Longevity among hunter‐gatherers: a cross‐cultural examination. Population and Development Review 33(2), 321–365.

Hamilton, M. I., Fernandez, D. P., and Nelson, S. V. 2021: Using strontium isotopes to determine philopatry and dispersal in primates: a case study from Kibale National Park. Royal Society Open Science 8(2), 200760.

Harvati, K., Röding, C., Bosman, A. M., Karakostis, F. A., Grün, R., Stringer, C., Karkanas, P., Thompson, N. C., Koutoulidis, V., and Moulopoulos, L. A. 2019: Apidima Cave fossils provide earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia. Nature 571(7766), 500–504.

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J. F., Jones, N. B., Alvarez, H., and Charnov, E. L. 1998: Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95(3), 1336–1339.

Hill, K. and Kaplan, H. 1999: Life history traits in humans: theory and empirical studies. Annual Review of Anthropology, 28(1), 397–430, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.28.1.397.

Hogg, R. 2018: Permanent record: the use of dental and bone microstructure to assess life history evolution and ecology. In D. P. Croft, D. F. Su, and S. W. Simpson (eds.), Methods in Paleoecology. Springer, 75–98.

Hogg, R., Lacruz, R., Bromage, T. G., Dean, M. C., Ramirez-Rozzi, F., Girimurugan, S. B., McGrosky, A., and Schwartz, G. T. 2020: A comprehensive survey of Retzius periodicities in fossil hominins and great apes. Journal of Human Evolution 149, 102896.

Hrdy, S. B. 2009: Mothers and others: the evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Harvard University Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dsiksDFQPDsC&oi=fnd&pg=PA1&dq=hrdy+mothers+and+others&ots=84Fr61vcWE&sig=J5DJhxbq5pZOr6UHkZSJ6xCSXaI

Hublin, J.-J., Ben-Ncer, A., Bailey, S. E., Freidline, S. E., Neubauer, S., Skinner, M. M., Bergmann, I., Le Cabec, A., Benazzi, S., and Harvati, K. 2017: New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens. Nature 546(7657), 289–292.

Hudson, J. M., Matthews, C. J., and Watt, C. A. 2021: Detection of steroid and thyroid hormones in mammalian teeth. Conservation Physiology 9(1), coab087.

Huffman, M. and Antoine, D. 2010: Analysis of cementum layers in archaeological material. Dental Anthropology Journal 23(3), 67–73.

Jeanson, A., Santos, F., Bruzek, J., and Urzel, V. 2016: Detecting menarcheal status through dental mineralization stages? American Journal of Physical Anthropology 161(2), 367–373.

Joannes-Boyau, R., Adams, J. W., Austin, C., Arora, M., Moffat, I., Herries, A. I., Tonge, M. P., Benazzi, S., Evans, A. R., and Kullmer, O. 2019: Elemental signatures of Australopithecus africanus teeth reveal seasonal dietary stress. Nature 572(7767), 112–115.

Jones, O. R., Scheuerlein, A., Salguero-Gómez, R., Camarda, C. G., Schaible, R., Casper, B. B., Dahlgren, J. P., Ehrlén, J., García, M. B., and Menges, E. S. 2014: Diversity of ageing across the tree of life. Nature 505(7482), 169–173.

Judge, D. S. and Carey, J. R. 2000: Postreproductive life predicted by primate patterns. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 55(4), B201–B209.

Kagayama, M., Li, H. C., Zhu, J., Sasano, Y., Hatakeyama, Y., and Mizoguchi, I. 1997: Expression of osteocalcin in cementoblasts forming acellular cementum. Journal of Periodontal Research 32(3), 273–278.

Kaplan, H., Hill, K., Lancaster, J., and Hurtado, A. M. 2000: A theory of human life history evolution: diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 9(4), 156–185, https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6505(2000)9:4<156::AID-EVAN5>3.0.CO;2-7.

Karaaslan, H., Seckinger, J., Almabrok, A., Hu, B., Dong, H., Xia, D., Dekyi, T., Hogg, R. T., Zhou, J., and Bromage, T. G. 2020: Enamel multidien biological timing and body size variability among individuals of Chinese Han and Tibetan origins. Annals of Human Biology, 1–7.

Karsenty, G. and Oury, F. 2014: Regulation of male fertility by the bone-derived hormone osteocalcin. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 382(1), 521–526.

Kay, R. F. and Cant, J. G. 1988: Age assessment using cementum annulus counts and tooth wear in a free‐ranging population of Macaca mulatta. American Journal of Primatology 15(1), 1–15.

Kay, R. F., Rasmussen, T., and Beard, C. 1984: Cementum annulus counts provide a means for age determination in Macaca mulatta (Primates, Anthropoidea). Folia Primatologica 42(2), 85–95.

Kelley, J. and Schwartz, G. T. 2012: Life-history inference in the early hominins Australopithecus and Paranthropus. International Journal of Primatology 33(6), 1332–1363, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-012-9607-2.

Kirkwood, T. B. and Shanley, D. P. 2010: The connections between general and reproductive senescence and the evolutionary basis of menopause. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1204(1), 21–29.

Klevezal, G. A. 1995: Recording structures of mammals. CRC Press.

Konner, M. 2017: Hunter-gatherer infancy and childhood: The! Kung and others. Hunter-Gatherer Childhoods, 19–64.

Kovacs, C. S. 2016: Maternal mineral and bone metabolism during pregnancy, lactation, and post-weaning recovery. Physiological Reviews 96(2): 449–547, doi:10.1152/physrev.00027.2015. PMID: 26887676.

Kralick, A. E., Loring Burgess, M., Glowacka, H., Arbenz‐Smith, K., McGrath, K., Ruff, C. B., Chan, K. C., Cranfield, M. R., Stoinski, T. S., and Bromage, T. G. 2017: A radiographic study of permanent molar development in wild Virunga mountain gorillas of known chronological age from R wanda. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 163(1), 129–147.

Kramer, K. L. 2010: Cooperative breeding and its significance to the demographic success of humans. Annual Review of Anthropology 39, 417–436.

Kramer, K. L. and Otárola-Castillo, E. 2015: When mothers need others: the impact of hominin life history evolution on cooperative breeding. Journal of Human Evolution 84, 16–24.

Kumagai, A., Fujita, Y., Endo, S., and Itai, K. 2012: Concentrations of trace element in human dentin by sex and age. Forensic Science International 219(1–3), 29–32.

Lacruz, R. S., Hacia, J. G., Bromage, T. G., Boyde, A., Lei, Y., Xu, Y., Miller, J. D., Paine, M. L., and Snead, M. L. 2012: The circadian clock modulates enamel development. Journal of Biological Rhythms 27(3), 237–245.

Lacruz, R. S., Rozzi, F. R., and Bromage, T. G. 2005. Dental enamel hypoplasia, age at death, and weaning in the Taung child. South African Journal of Science 101(11), 567–569.

Lahdenperä, M., Lummaa, V., Helle, S., Tremblay, M., and Russell, A. F. 2004: Fitness benefits of prolonged post-reproductive lifespan in women. Nature 428(6979), 178–181.

Le Bourg, E., Thon, B., Légaré, J., Desjardins, B., and Charbonneau, H. 1993: Reproductive life of French-Canadians in the 17–18th centuries: a search for a trade-off between early fecundity and longevity. Experimental Gerontology 28(3), 217–232.

Le Cabec, A., Tang, N. K., Ruano Rubio, V., and Hillson, S. 2019: Nondestructive adult age at death estimation: visualizing cementum annulations in a known age historical human assemblage using synchrotron X‐ray microtomography. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 168(1), 25–44.

Lee, N. K., Sowa, H., Hinoi, E., Ferron, M., Ahn, J. D., Confavreux, C., Dacquin, R., Mee, P. J., McKee, M. D., and Jung, D. Y. 2007: Endocrine regulation of energy metabolism by the skeleton. Cell 130(3), 456–469.

Leigh, S. R. 2001: Evolution of human growth. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 10(6), 223–236.

Lemmers, S. A., Dirks, W., Street, S. E., Ngoubangoye, B., Herbert, A., and Setchell, J. M. 2021: Dental microstructure records life history events: a histological study of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) from Gabon. Journal of Human Evolution 158, 103046.

Lieberman, D. E., Kistner, T. M., Richard, D., Lee, I.-M., and Baggish, A. L. 2021: The active grandparent hypothesis: physical activity and the evolution of extended human healthspans and lifespans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118(50).

Liversidge, H. M. 2008: Timing of human mandibular third molar formation. Annals of Human Biology 35(3), 294–321.

Lonsdorf, E. V., Stanton, M. A., Pusey, A. E., and Murray, C. M. 2020: Sources of variation in weaned age among wild chimpanzees in Gombe National Park, Tanzania. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 171(3), 419–429.

MacArthur, R. H. and Wilson, E. O. 1967: The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press.

MacAvoy, S. E., Arneson, L. S., and Bassett, E. 2006: Correlation of metabolism with tissue carbon and nitrogen turnover rate in small mammals. Oecologia 150(2), 190–201.

Macchiarelli, R., Bondioli, L., Debénath, A., Mazurier, A., Tournepiche, J.-F., Birch, W., and Dean, M. C. 2006: How Neanderthal molar teeth grew. Nature 444(7120), 748–751.

Mace, R. 2000: Evolutionary ecology of human life history. Animal Behaviour 59(1), 1–10.

Mahoney, P. 2015: Dental fast track: prenatal enamel growth, incisor eruption, and weaning in human infants. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 156(3), 407–421, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22666.

Mahoney, P., McFarlane, G., Smith, B. H., Miszkiewicz, J. J., Cerrito, P., Liversidge, H., Mancini, L., Dreossi, D., Veneziano, A., and Bernardini, F. 2021: Growth of Neanderthal infants from Krapina (120–130 ka), Croatia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 288(1963), 20212079.

Martrille, L., Ubelaker, D. H., Cattaneo, C., Seguret, F., Tremblay, M., and Baccino, E. 2007: Comparison of four skeletal methods for the estimation of age at death on white and black adults. Journal of Forensic Sciences 52(2), 302–307.

McFadden, C., Cave, C. M., and Oxenham, M. F. 2019: Ageing the elderly: a new approach to the estimation of the age‐at‐death distribution from skeletal remains. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 29(6), 1072–1078.

McGrath, K., Limmer, L. S., Lockey, A.-L., Guatelli-Steinberg, D., Reid, D. J., Witzel, C., Bocaege, E., McFarlin, S. C., and El Zaatari, S. 2021: 3D enamel profilometry reveals faster growth but similar stress severity in Neanderthal versus Homo sapiens teeth. Scientific Reports, 11.

Medill, S., Derocher, A. E., Stirling, I., and Lunn, N. 2010: Reconstructing the reproductive history of female polar bears using cementum patterns of premolar teeth. Polar Biology 33(1), 115–124.

Nava, A., Coppa, A., Coppola, D., Mancini, L., Dreossi, D., Zanini, F., Bernardini, F., Tuniz, C., and Bondioli, L. 2017: Virtual histological assessment of the prenatal life history and age at death of the Upper Paleolithic fetus from Ostuni (Italy). Scientific Reports 7(1), 1–10.

Nava, A., Lugli, F., Lemmers, S., Cerrito, P., Mahoney, P., Bondioli, L., and Müller, W. 2024: Reading children’s teeth to reconstruct life history and the evolution of human cooperation and cognition: the role of dental enamel microstructure and chemistry. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 163, 105745, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105745.

Nava, A., Lugli, F., Romandini, M., Badino, F., Evans, D., Helbling, A. H., Oxilia, G., Arrighi, S., Bortolini, E., and Delpiano, D. 2020: Early life of Neanderthals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(46), 28719–28726.

Nejad, J. G., Jeong, C., Shahsavarani, H., Sung, K. I. L., and Lee, J. 2016: Embedded dental cortisol content: a pilot study. Endocrinol Metab Syndr 5(240), 2161-1017.1000240.

Newham, E., Corfe, I. J., Brown, K. R., Gostling, N. J., Gill, P. G., and Schneider, P. 2020: Synchrotron radiation-based X-ray tomography reveals life history in primate cementum incrementation. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 17(172), 20200538.

Newham, E., Gill, P. G., Brewer, P., Benton, M. J., Fernandez, V., Gostling, N. J., Haberthür, D., Jernvall, J., Kankaanpää, T., and Kallonen, A. 2020: Reptile-like physiology in Early Jurassic stem-mammals. Nature Communications 11(1), 1–13.

Newham, E., Gill, P. G., Robson Brown, K., Gostling, N. J., Corfe, I. J., and Schneider, P. 2021: A robust, semi-automated approach for counting cementum increments imaged with synchrotron X-ray computed tomography. PloS One 16(11), e0249743.

Page, A. E., Dyble, M., Migliano, A., Chaudhary, N., Viguier, S., and Major-Smith, D. 2025: Demography of grandmothering – a case study in Agta foragers. https://osf.io/76eka/download.

Page, A. E., Minter, T., Viguier, S., and Migliano, A. B. 2018: Hunter-gatherer health and development policy: how the promotion of sedentism worsens the Agta’s health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine 197, 39–48.

Page, A. E., Ringen, E. J., Koster, J., Borgerhoff Mulder, M., Kramer, K., Shenk, M. K., Stieglitz, J., Starkweather, K., Ziker, J. P., Boyette, A. H., Colleran, H., Moya, C., Du, J., Mattison, S. M., Greaves, R., Sum, C.-Y., Liu, R., Lew-Levy, S., Kiabiya Ntamboudila, F., Sear, R., et al. 2024: Women’s subsistence strategies predict fertility across cultures, but context matters. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121(9), e2318181121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2318181121.

Panciroli, E., Benson, R. B., Fernandez, V., Fraser, N. C., Humpage, M., Luo, Z.-X., Newham, E., and Walsh, S. 2024: Jurassic fossil juvenile reveals prolonged life history in early mammals. Nature 632(8026), 815–822.

Pazzaglia, U. E., Congiu, T., Marchese, M., Spagnuolo, F., and Quacci, D. 2012: Morphometry and patterns of lamellar bone in human Haversian systems. The Anatomical Record: Advances in Integrative Anatomy and Evolutionary Biology 295(9), 1421–1429.

Pereira, M. E. and Leigh, S. R. 2003: Modes of primate development. Primate life histories and socioecology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 149–176.

Pettay, J. E., Kruuk, L. E., Jokela, J., and Lummaa, V. 2005: Heritability and genetic constraints of life-history trait evolution in preindustrial humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(8), 2838–2843.

Pignolo, R. J. 2019: Exceptional human longevity. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 94(1), 110–124, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025619618307924.

Prilepskaya, N. E., Belyaev, R. I., Burova, N. D., Bachura, O. P., and Sinitsyn, A. A. 2020: Determination of season-of-death and age-at-death by cementum increment analysis of horses Equus ferus (Boddaert, 1785) from cultural layer IVa at Upper Paleolithic site Kostenki 14 (Markina Gora)(Voronezh region, Russia). Quaternary International 557, 110–120.

Quade, L., Chazot, P. L., and Gowland, R. 2021: Desperately seeking stress: a pilot study of cortisol in archaeological tooth structures. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 174(3), 532–541.

Quade, L., Králík, M., Bencúrová, P., and Dunn, E. C. 2023: Cortisol in deciduous tooth tissues: a potential metric for assessing stress exposure in archaeological and living populations. International Journal of Paleopathology 43, 1–6.

Rahnama, M. 2002: Influence of estrogen deficiency on the copper level in rat teeth and mandible. Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska. Sectio D: Medicina 57(1), 352–356.

Robson, S. L., van Schaik, C. P., and Hawkes, K. 2006: The derived features of human life history. In: K. Hawkes and R. R. Paine (eds.), The evolution of human life history. Santa Fe: SAR, 17–44.

Robson, S. L. and Wood, B. 2008: Hominin life history: reconstruction and evolution. Journal of Anatomy 212(4), 394–425.

Rozzi, F. V. R. and De Castro, J. M. B. 2004: Surprisingly rapid growth in Neanderthals. Nature 428(6986), 936–939.

Ryan, J., Stulajter, M. M., Okasinski, J. S., Cai, Z., Gonzalez, G. B., and Stock, S. R. 2020: Carbonated apatite lattice parameter variation across incremental growth lines in teeth. Materialia 14, 100935.

Schultz, A. H. 1949: Ontogenetic specializations of man. Arch Julius Klaus-Stift 24, 197–216.

Schwartz, G. T. 2012: Growth, development, and life history throughout the evolution of Homo. Current Anthropology 53(S6), S395–S408.

Seebacher, F. 2009: Responses to temperature variation: integration of thermoregulation and metabolism in vertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology 212(18), 2885–2891.

Sellen, D. W. 2001: Comparison of infant feeding patterns reported for nonindustrial populations with current recommendations. The Journal of Nutrition 131(10), 2707–2715.

Seriwatanachai, D., Thongchote, K., Charoenphandhu, N., Pandaranandaka, J., Tudpor, K., Teerapornpuntakit, J., Suthiphongchai, T., and Krishnamra, N. 2008: Prolactin directly enhances bone turnover by raising osteoblast-expressed receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand/osteoprotegerin ratio. Bone 42(3), 535–546.

Sharma, D., Larriera, A. I., Palacio-Mancheno, P. E., Gatti, V., Fritton, J. C., Bromage, T. G., Cardoso, L., Doty, S. B., and Fritton, S. P. 2018: The effects of estrogen deficiency on cortical bone microporosity and mineralization. Bone 110, 1–10.

Silk, H., Douglass, A. B., Douglass, J. M., and Silk, L. 2008: Oral health during pregnancy. American Family Physician 77(8), 1139–1144.

Smith, B. H. 1984: Rates of molar wear-implications for developmental timing and demography in human-evolution. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 63(2), 220–220.

Smith, B. H. 1989: Dental development as a measure of life history in primates. Evolution 43(3), 683–688.

Smith, B. H., Crummett, T. L., and Brandt, K. L. 1994: Ages of eruption of primate teeth: a compendium for aging individuals and comparing life histories. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 37(S19), 177–231.

Smith, B. H. and Tompkins, R. L. 1995: Toward a life history of the Hominidae. Annual Review of Anthropology 24(1), 257–279, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.001353.

Smith, T. M. 2013: Teeth and human life-history evolution. Annual Review of Anthropology 42(1), 191–208, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155550.

Smith, T. M. 2016: Dental development in living and fossil orangutans. Journal of Human Evolution 94, 92–105.

Smith, T. M., Arora, M., Bharatiya, M., Dirks, W., and Austin, C. 2023: Elemental models of primate nursing and weaning revisited. American Journal of Biological Anthropology 180(1), 216–223, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24655.

Smith, T. M., Austin, C., Green, D. R., Joannes-Boyau, R., Bailey, S., Dumitriu, D., Fallon, S., Grün, R., James, H. F., and Moncel, M.-H. 2018: Wintertime stress, nursing, and lead exposure in Neanderthal children. Science Advances 4(10), eaau9483.

Smith, T. M., Smith, B. H., Reid, D. J., Siedel, H., Vigilant, L., Hublin, J.-J., and Boesch, C. 2010: Dental development of the Taï Forest chimpanzees revisited. Journal of Human Evolution 58(5), 363–373.

Smith, T. M., Tafforeau, P., Cabec, A. L., Bonnin, A., Houssaye, A., Pouech, J., Moggi-Cecchi, J., Manthi, F., Ward, C., Makaremi, M., and Menter, C. G. 2015: Dental ontogeny in Pliocene and early Pleistocene hominins. PLOS ONE 10(2), e0118118, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118118.

Smith, T. M., Tafforeau, P., Reid, D. J., Grün, R., Eggins, S., Boutakiout, M., and Hublin, J.-J. 2007: Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104(15), 6128–6133.

Smith, T. M., Tafforeau, P., Reid, D. J., Pouech, J., Lazzari, V., Zermeno, J. P., Guatelli-Steinberg, D., Olejniczak, A. J., Hoffman, A., and Radovčić, J. 2010: Dental evidence for ontogenetic differences between modern humans and Neanderthals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(49), 20923–20928.

Sultana, A., Zainab, H., Jahagirdar, P., and Hugar, D. 2021: Age estimation with cemental incremental lines in normal and periodontally diseased teeth using phase contrast microscope: an original research. Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences 11(1), 1–9.

Takken Beijersbergen, L. M. 2019: Determining age and season of death by use of incremental lines in Norwegian reindeer tooth cementum. Environmental Archaeology 24(1), 49–60.

Tanner, C., Rodgers, G., Schulz, G., Osterwalder, M., Mani-Caplazi, G., Hotz, G., Scheel, M., Weitkamp, T. and Müller, B. 2021: Extended-field synchrotron microtomography for non-destructive analysis of incremental lines in archeological human teeth cementum. Developments in X-Ray Tomography XIII 11840, 1184019.

Tobias, P. V. 2006: Longevity, death and encephalisation among Plio-Pleistocene hominins. International Congress Series 1296, 1–15.

Trinkaus, E. 1995: Neanderthal mortality patterns. Journal of Archaeological Science 22(1), 121–142.

Trotter, M., Hixon, B. B., and MacDonald, B. J. 1977: Development and size of the teeth of Macaca mulatta. American Journal of Anatomy 150(1), 109–127.

Trumble, S. J., Norman, S. A., Crain, D. D., Mansouri, F., Winfield, Z. C., Sabin, R., Potter, C. W., Gabriele, C. M., and Usenko, S. 2018: Baleen whale cortisol levels reveal a physiological response to 20th century whaling. Nature Communications 9(1), 1–8.

Tully, T. and Lambert, A. 2011: The evolution of postreproductive life span as an insurance against indeterminacy. Evolution: International Journal of Organic Evolution 65(10), 3013–3020.

Turunen, M. J., Kaspersen, J. D., Olsson, U., Guizar-Sicairos, M., Bech, M., Schaff, F., Tägil, M., Jurvelin, J. S., and Isaksson, H. 2016: Bone mineral crystal size and organization vary across mature rat bone cortex. Journal of Structural Biology 195(3), 337–344.

van Heteren, A. H., King, A., Berenguer, F., Mijares, A. S., and Detroit, F. 2023: Cementochronology using synchrotron radiation tomography to determine age at death and developmental rate in the holotype of Homo luzonensis. bioRxiv 2023.02. 13.528294.

van Schaik, C. P. and Burkart, J. M. 2010: Mind the gap: cooperative breeding and the evolution of our unique features. In: P. M. Kappeler and J. Silk (eds.), Mind the gap. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 477–496, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-02725-3_22.

Veiberg, V., Nilsen, E. B., Rolandsen, C. M., Heim, M., Andersen, R., Holmstrøm, F., Meisingset, E. L., and Solberg, E. J. 2020: The accuracy and precision of age determination by dental cementum annuli in four northern cervids. European Journal of Wildlife Research 66(6), 1–11.

Volk, A. A. 2023: Historical and hunter-gatherer perspectives on fast-slow life history strategies. Evolution and Human Behavior 44(2), 99–109.

Von Biela, V. R., Testa, J. W., Gill, V. A., and Burns, J. M. 2008. Evaluating cementum to determine past reproduction in northern sea otters. The Journal of Wildlife Management 72(3), 618–624.

Walker, R., Gurven, M., Hill, K., Migliano, A., Chagnon, N., De Souza, R., Djurovic, G., Hames, R., Hurtado, A. M., and Kaplan, H. 2006: Growth rates and life histories in twenty‐two small‐scale societies. American Journal of Human Biology: The Official Journal of the Human Biology Association 18(3), 295–311.

Weber, D. F. and Eisenmann, D. R. 1971: Microscopy of the neonatal line in developing human enamel. American Journal of Anatomy 132(3), 375–391.

Wittwer‐Backofen, U., Gampe, J., and Vaupel, J. W. 2004: Tooth cementum annulation for age estimation: results from a large known‐age validation study. American Journal of Physical Anthropology: The Official Publication of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists 123(2), 119–129.

Wood, B. M., Negrey, J. D., Brown, J. L., Deschner, T., Thompson, M. E., Gunter, S., Mitani, J. C., Watts, D. P., and Langergraber, K. E. 2023: Demographic and hormonal evidence for menopause in wild chimpanzees. Science 382(6669), eadd5473, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add5473.

Zihlman, A., Bolter, D., and Boesch, C. 2004: Wild chimpanzee dentition and its implications for assessing life history in immature hominin fossils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101(29), 10541–10543.

Zollikofer, C. P., Beyrand, V., Lordkipanidze, D., Tafforeau, P., and Ponce de León, M. S. 2024: Dental evidence for extended growth in early Homo from Dmanisi. Nature, 1–6.