Abstract

The Saalian phase of the Middle Paleolithic (MIS 8 to 6) in northern France, as with Belgium and the Rhine Valley, has been characterized by a poor archaeological record, which seems to reflect discontinuous human occupation of these areas. All of the methods of lithic production from the Middle Paleolithic have been identified, with laminar debitage evident as well (Therdonne, Rheindalen, etc.). In this extensive geographical area, interglacial occupations (SIM 5e) are difficult to identify (Caours, Waziers, Lehringen, Neumark-Nord, Veldwezelt Hezerwater, etc.), largely for taphonomic reasons.

During the beginning of the last glaciation (MIS 5d to 5a), several sites seem to show considerable similarities in systems of technological production (Seclin, Bettencourt-Saint-Ouen, Rémicourt, Tönchesberg, Wallertheim, etc.). Considered on a large scale, human occupations seem to be part of the same “technocomplex.” During this long phase of climatic transition, the settlement of the northwest appears to be significant and continuous.

The end of the Middle Paleolithic (MIS 4 and 3) is characterized by greater cultural diversity, which seems to distinguish these three regions, and human occupation appears to be discontinuous.

Introduction

The aim of this article is to provide a French response to the question formulated in the title of this book: Was the Rhine a boundary or a corridor during the Middle Paleolithic? It is clear that the Rhine was difficult to cross during interglacial periods, as it is now, and it appears to have acted as a boundary during the Roman Empire, undoubtedly due to a notion attributed to Julius Caesar (Dignef 2013).

A parallel can be drawn with the Channel River, which isolated Great Britain from the continent at times, for example during isotope stages 6 and 5. But the large plains of the North Sea were dewatered during glacial phases and were crossed by herds of large herbivores and groups of nomadic hunters (Roebroeks 2014). On a smaller scale, the Rhine could also have acted as a boundary, or in any case as an obstacle, and may have been easier to cross during climatic fluctuations in the Pleistocene.

Over the past few years, regional overviews have been established for the North of France (Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Picardy; see Locht and Depaepe 2015; Hérisson et al. 2016; Locht et al. 2016), but also for Belgium, a close neighbor of the Rhine Valley (Di Modica et al. 2016). A similar review was recently carried out for Germany (Richter 2016). Modern archaeological methods now allow us to make a certain number of comparisons in these three geographical areas.

Further south, Alsace appears to have been more deserted during the Middle Paleolithic, where the only sites recorded in the literature are Mutzig (Koehler et al. 2016) and the early discoveries at Achenheim (Heim et al. 1982; Junkmann 1995). However, this situation may result from several factors: the absence of Paleolithic archaeological activity for years; the paucity of lithic raw materials or the thickness of the loess cover masking sites. But it is clear that Paleolithic hunters crossed these zones, as shown by the surface site of Lellig in Luxemburg (Le Brun-Ricalents et al. 2013), or the Magdalenian occupations at Morschwiller (Koehler et al. 2013).

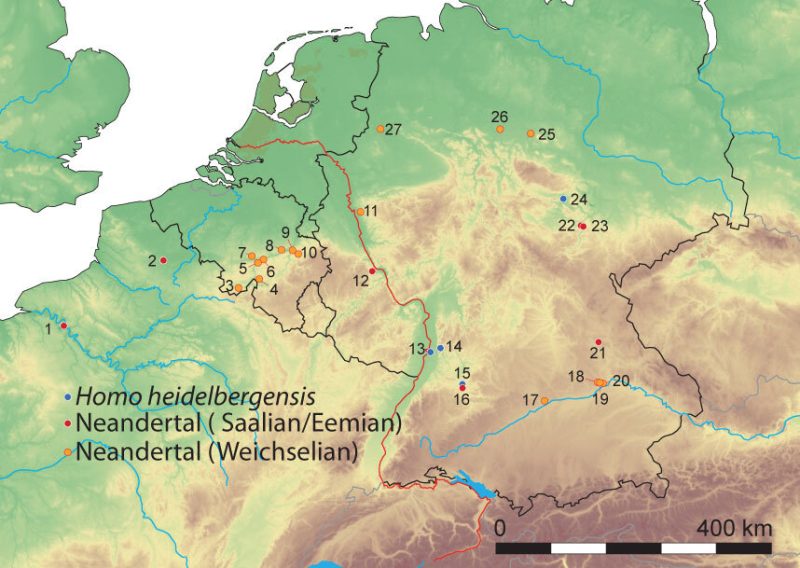

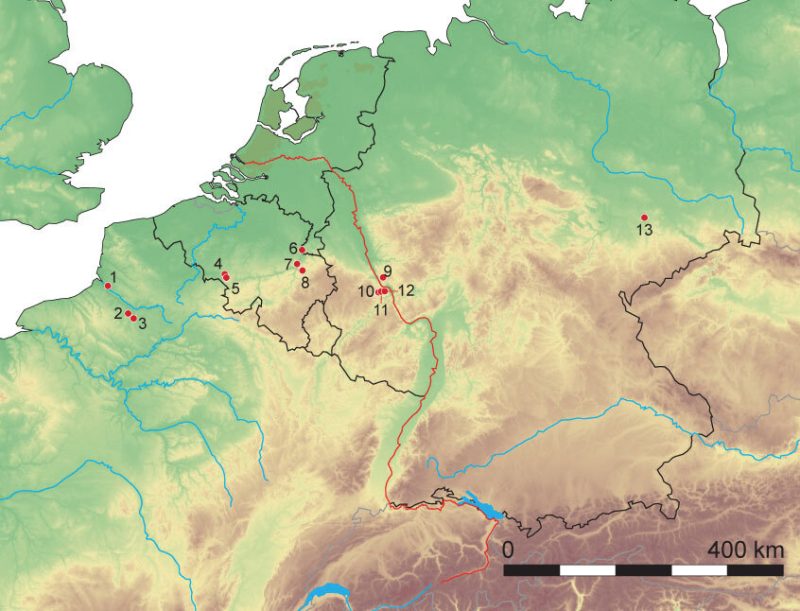

On both sides of the Rhine, archaeological material/sites from northern France, Belgium and Germany offer extensive data for our understanding of the Middle Paleolithic. This article aims to bring to light the similarities and disparities among these geographical areas, which marked the northern margins of Neanderthal expansion and which were discontinuously settled in different ways during the different chrono-climatic phases (Fig. 1).

The Human Fossil Record

The sediments of the plains in northern France are generally decarbonated and are not conducive to the preservation of bone remains. For the Middle Paleolithic period, only two sites have yielded human remains attributed to Neanderthals: two skulls found at Biache-Saint-Vaast (Tuffreau and Sommé 1988) and an arm found at Tourville-la-Rivière (Faivre et al. 2014). Both sites consist of fine and calcareous fluviatile sediments attributed to MIS 7.

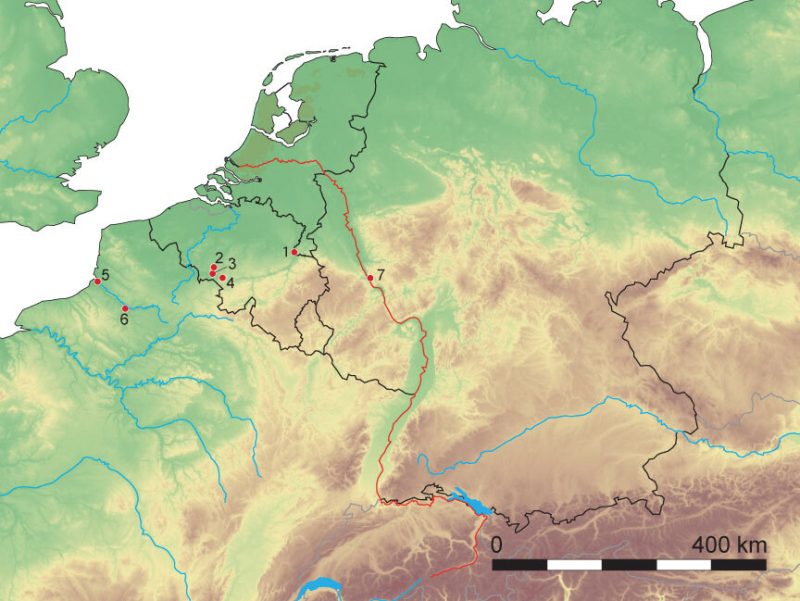

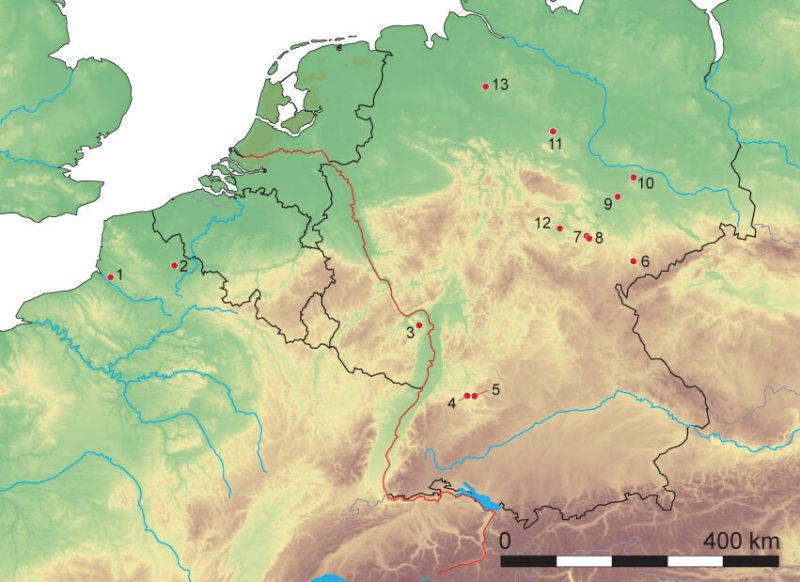

In comparison, the Meuse corridor in Belgium contains abundant Neanderthal fossils (Fig. 2). Remains of this hominin have been found in eight cave sites (Engis, Spy, Goyet, Sclayn, Trou Walou, Couvin, La Naulette, Fonds-de-Forêt). The minimum number of individuals for the Belgian Neanderthal sites is 10 (Toussaint et al. 2011). The context of the human remains from Engis, Goyet and Fonds-de-Forêt cannot be interpreted. On the other hand, those from Sclayn and perhaps La Naulette go back to the beginning of the Weichselian Glacial. Finally, the remains from Trou Walou, Couvin and Spy are “classic” Weichselian Neanderthals.

The German human fossils come from cave or open-air sites, generally preserved in alluvial sediments, including travertines. The Mauer mandible, discovered in 1907 and dated to 609,000 ± 40,000 years, has been defined as the Homo heidelbergensis holotype (Wagner et al. 2010). It is linked to the middle phase of the Middle Pleistocene. Other fossils attributed to Homo erectus or Homo heidelbergensis were found at Bilzingsleben (MIS 11), Stuttgart Bad Cannstatt, Steinheim (MIS 9?), whereas the age of the skull from Reilingen is still debated (Street et al. 2006). This is also the case for the skull fragments from Ehringsdorf (MIS 7 or 5e). The site of Ochtendung yielded remains attributable to MIS 6 (von Berg et al. 2000).

For the Upper Pleistocene, the two molars from Taubach are attributed to the Eemian (MIS 5e). Finally, seven sites, including the eponymous site, contain Weichselian Neanderthal remains: Neandertal, Warendorf, Salzgitter-Lebenstedt, Sarstedt, Hohlenstein-Stadel, Sesselfelsgrotte and Klaussennische (Street et al. 2006).

Mis 8, the Beginning of the Middle Paleolithic

Generally speaking, the Middle Paleolithic is said to begin with the emergence of the Levallois, in particular, with Levallois debitage. This process is well documented at the site of Kesselt Op de Schans in Belgium, where four lithic concentrations attributed to the beginning of MIS 8 show the presence of Levallois, Discoid and prepared core technology (Van Baelen et al. 2007). A recent revision of the alluvial formations from Mesvin IV could confer an age of 350 ka BP on the Levallois debitage assemblage from this site (Haesaerts et al. 2019).

In the Somme Valley, one of the first signs of Levallois debitage was found at Salouel in the gravels of “the Argoeuvres sheet” (Antoine 1990) and appears to date from the end of isotope stage 8 (Fig. 3).

In Germany, the stratigraphic position of the lithic assemblage from Ariendorf 1, situated under the Wehr tephra, and dated to 220 ka BP, makes it one of the earliest indications of the Middle Paleolithic (Richter 2006).

In these three regions, Levallois debitage seems to become widespread during MIS 8, although this lower limit is likely to be pushed further back in the near future (Locht et al. 2018).

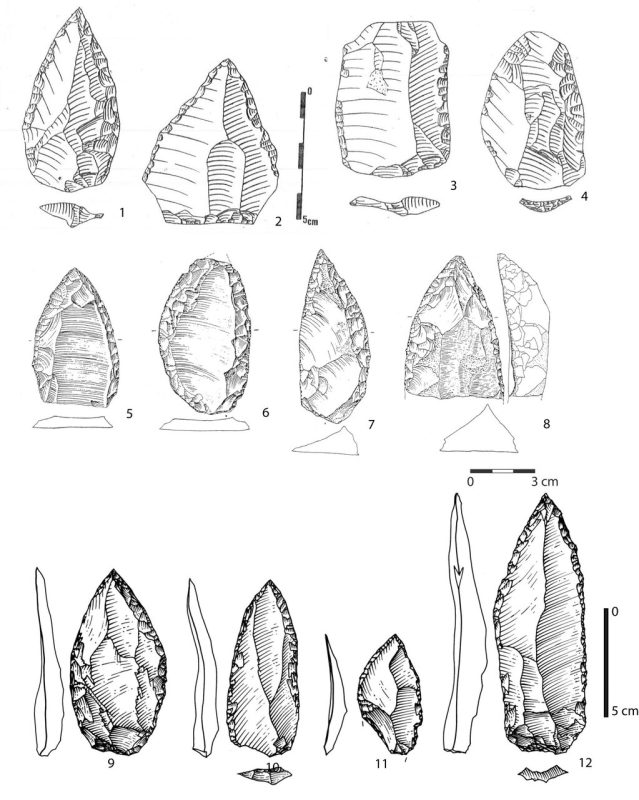

Mis 7, a Ferrassie-Type Mousterian

On a broader geographic scale, several lithic assemblages have been linked to a Ferrassie-type Mousterian. This is the case for Biache-Saint-Vaast, in northern France (Sommé and Tuffreau 1988), Level B3 at Rheindahlen in the Rhine Valley (Bosinski 1995) and Site K at Maastricht-Belvédère (Verpoorte et al. 2016). Similarities between the retouched toolkits from these sites imply that there is a degree of cultural unity in north-western Europe during MIS 7. During the rest of the Middle Paleolithic, this Mousterian facies is only barely represented, or completely absent, in northern Europe (Figs. 4 and 5).

Assemblages with a Laminar Component from Mis 7

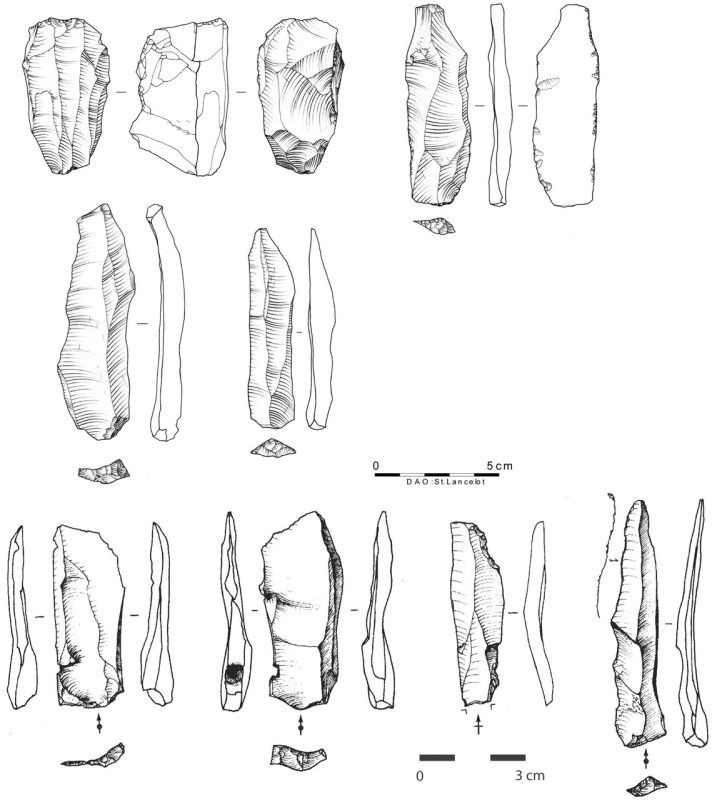

From the beginning of the Middle Paleolithic, all the lithic production systems (Mousterian biface shaping, Levallois, laminar, discoid debitage, etc.) already appear to be perfectly mastered (Locht 2005). In northwest Europe, several sites show the presence of laminar production from the Saalian phase of the Middle Paleolithic onwards. This is well illustrated at the site of Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme (France) at the end of MIS 8 or the beginning of MIS 7 (de Heinzelin and Haesaerts 1983). The N3 series from Therdonne, which also dates from the transition between MIS 7 and 6, also contains a small, but well-mastered, laminar component (Locht et al. 2010).

In Belgium, the lithic series from Rissori also contains a small laminar component, represented by prismatic cores and several crested blades (Adam 1991).

In Germany, after a recent revision of the Rheindahlen stratigraphy, the B1 occupation level was surprisingly attributed to MIS 7 (Schirmer 2016; Richter 2016). Up until then, the chronostratigraphic context of this occupation seemed to be well established, with an attribution to MIS 5 (Bosinski 1995). But an older age for Level B1 is nonetheless consistent with the archaeological record from MIS 7 in northern Europe, as shown by the series with laminar components from Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme, Therdonne and Rissori.

The Mis 6 Occupations

The Pleniglacial phase of this isotope stage undoubtedly led to the abandonment of northern Europe during the most extreme phases, interspersed with small human incursions during short phases of climatic amelioration. Only a few archaeological levels in these three geographic areas can be attributed to this long period (Fig. 6).

In northern France, Ailly-sur-Noye is attributed to a Tardiglacial context on account of its stratigraphic position and in particular, the malacological study of Level 3 (Locht et al. 2013).

The Interglacial Eemian Occupations (Mis 5e)

Until recently, Middle Paleolithic occupations during the Eemian in northern and central Europe were only recorded at German, Slovak and Hungarian sites, within travertines or lacustrine sediments. No sites from this period were known in north-western Europe. Based on the available data, certain authors put forward a “green barrier” theory, according to which Neanderthals could not adapt their lifestyle to a temperate climate and a closed, wooded environment (Gamble 1986). For others, taphonomic-related factors were responsible for the absence of Eemian sites, as the erosive action of the last glacial erased interglacial deposits (Roebroeks and Speelers 2002). The discovery of the site of Caours in 2002 confirmed the latter explanation (Antoine et al. 2006). The archaeological levels preserved in fine fluviatile sediments were protected from erosion by the upper part of the stratigraphic sequence, made up of much more solid coarse tufas. Since then, the discovery of the site of Waziers showed that this Neanderthal presence during the Eemian in northern France was not an isolated case (Hérisson et al. 2017). The absence of Eemian occupations, in the strict sense of the term, in Belgium is also undoubtedly due to taphonomic factors in caves and in open-air sites (Fig. 7).

These recent discoveries modify our perception of settlement patterns in Europe during the Pleistocene. Hominins were present in north-western Europe during the Eemian interglacial, as could logically be expected in light of the settlement observed during the preceding interglacial phases. However, the level of current research does not enable us to estimate Neanderthal demography during the Eemian.

After an overview of the literature, it is fitting to make some general observations about lithic assemblages (Wenzel 2007; Pop 2014; Locht and Depaepe 2015; Hérisson et al. 2017). Levallois and Discoid debitages are well represented, but these series seem to be characterized by relatively low levels of technical investment and are of rather average quality.

The difficulties related to sourcing good quality raw materials in a closed, wooded environment may partially account for this (Locht et al. 2014). However, other hypotheses can be put forward, such as the theory that stone tools played a secondary role in relation to other easily accessible raw materials, such as wood, in interglacial contexts (Otte 2015). The Lehringen spear, which dates to the Eemian, and the older spears from Schöningen are remarkable examples of this (Thieme and Veil 1985; Thieme 1997). Wooden artifacts are rarely preserved, and when they are, they shed light on the vegetal component of the Neanderthal hunting toolkit panoply. The use of bitumen for hafting stone tools has been recorded at certain sites in the Near East, implying that sophisticated hafting methods were used for stone tools (Boëda et al. 2008).

The discoveries from Caours and Waziers complete and broaden the Eemian Paleolithic landscape based on German sites. They underline the adaptive faculties of Neanderthals to temperate climates or to Periglacial climates like at Beauvais (Locht et al. 2014).

Early Weichselian Assemblages With A Laminar Component (Mis 5d To 5a)

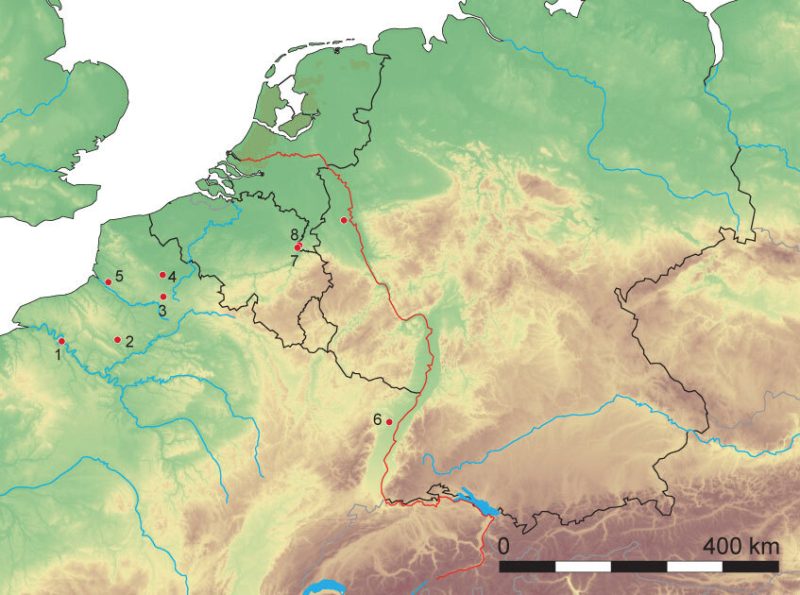

During the Early Weichselian glacial period (MIS 5d to 5a), an original technocomplex developed in northern France (Figs. 8 and 9). Levallois debitage provides the backdrop for this technocomplex, but it is frequently associated with blade production on prismatic cores and point production on convergent unipolar cores (Locht 2005; Goval 2008; Locht et al. 2016). Altogether, 33 archaeological levels have been attributed to the early Weichselian and are divided into sub-stages 5b, 5c and 5b, with an absence of occupation during MIS 5b.

Equivalent assemblages in Belgium include the lithic assemblages from Rémicourt and Mont Saint-Martin in Liège (MIS 5b: Van Der Sloot et al. 2011; Bosquet et al. 2004) and Rocourt (MIS 5c: Otte et al. 1990). This type of laminar production is only found in open-air sites and has not been identified in caves (Di Modica et al. 2016).

In Germany, this technocomplex could be represented by the occupation levels at Tönchesberg 2B (MIS 5d) and Wallertheim D (MIS 5a). In the first site, lithic production is geared towards flakes and blades (Conard 1992). The second is characterized by laminar production (Conard and Adler 1996). For a long time, Level B1 at Rheindahlen was attributed to MIS 5 (Bosinski 1995). In view of the discovery date of the site in 1966, it would even have been logical to group assemblages with a laminar component under the term “Rheindahlian,” as suggested by G. Bosinski (1967). If we accept that Rheindahlen B1 is contemporaneous with the Early Weichselian Glacial, it would incorporate seamlessly within the northern European archaeological landscape (Locht et al. 2010).

This technocomplex characterizes north-western Europe, but does not extend beyond the Rhine, which seems to represent a boundary in this specific case. Tönchesberg and Wallertheim are both on the left bank. Up until now, no assemblages with laminar components have been found further east; the laminar productions at Piekary II and Cracow are more recent (MIS 4 or 3: Kozlowski 2001, 2002, 2006; Valladas et al. 2003).

The Lower and Middle Pleniglacial: A Contrasted Cultural Mosaic

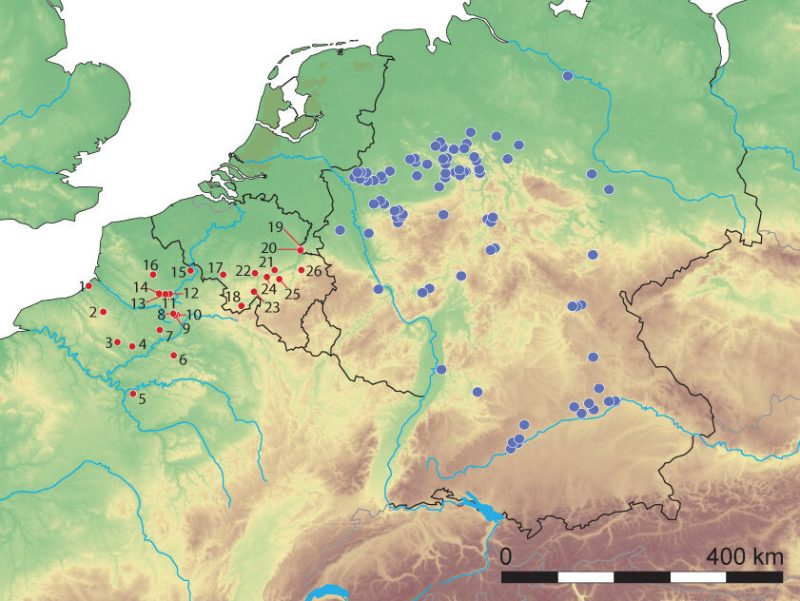

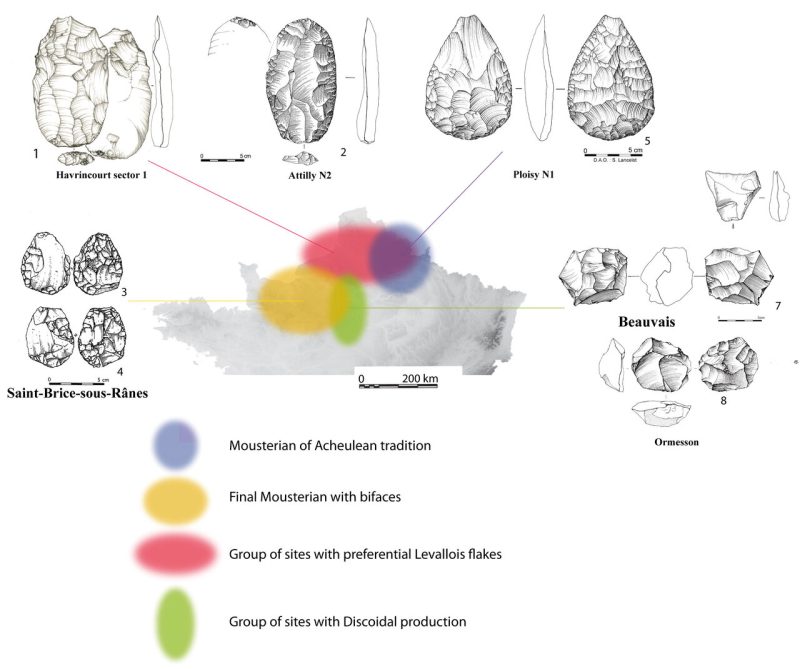

No human occupation has been recorded during the Lower Weichselian Pleniglacial (MIS 4) in Germany (Richter 2016). Until recently, this was also true of northern France, which seemed to be completely uninhabited (Locht 2004). However, the discoveries of the occupation levels of Havrincourt, dated by OSL to 65 ± 3.8 and 67.6 ± 3.9 ka (Antoine et al. 2014) and of Catigny (OSL: 62.66 ± 4 ka; Locht 2018) challenge this interpretation (Fig. 10). These brief traces of human occupation must have occurred during the Lower Pleniglacial interstadials (MIS 4). Then, during the Middle Pleniglacial (MIS 3), the archaeological record takes the form of a contrasted cultural mosaic with the presence of sites attributed to the Mousterian with denticulates (Beauvais, including the site of Ormesson; Bodu et al. 2013) or to the Mousterian of Acheulean tradition (Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, Ploisy)(Fig. 11). Sites characterized by the presence of preferential Levallois flakes make up a third group (Ault, Gauville, Attilly, Hermies; Locht et al 2016). The last Middle Paleolithic occurrences take place at about 40 ka (Hénin-sur-Cojeul; Marcy et al. 1993).

If we look to eastern France, the Rhine may have been a north/south communication path with the diffusion of Keilmessergruppen-type assemblages in the south of Burgundy (Frick and Floss 2017).

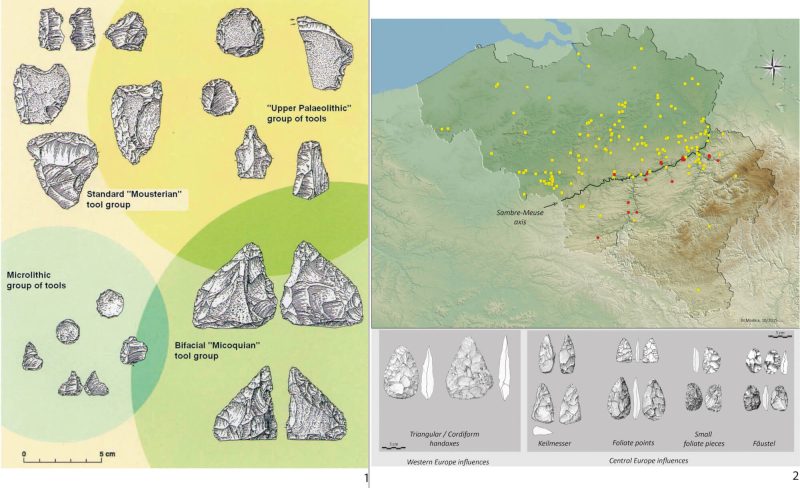

In Belgium, the situation seems to be much the same as in northern France. Tenuous traces of occupations are recorded during the Lower Pleniglacial (MIS 4) in Harmignies and Trou Walou, for example (Di Modica et al. 2016). During the Middle Pleniglacial, traces of human occupations become more frequent (Veldwezelt, Couvin, Trou Walou, Sclayn, Spy, etc.), but none seem to be older than 45 ka BP (Di Modica et al. 2016).

The leaf-shaped points found at Couvin suggest eastern affinities with “Micoquian” groups from Germany (Blattspitzen), whereas others point to links with the Mousterian of Acheulean tradition, which would place Belgium at the junction between two different cultural areas (Di Modica et al. 2016).

Neanderthals are present in Belgium until about 38/37 ka BP, as shown by the 14C dates obtained during the recent revision of the Spy fossils (Semal et al. 2009). These dates imply that Neanderthals may also be the artisans of the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanovician, which begins at about 38,000 BP (LRJ; Flas 2013 and 2015). However, this hypothesis has not yet been confirmed (Pirson et al. 2011). Most of the last Mousterian levels are slightly older. The stratigraphic position of Layer 1A at Sclayn suggests an age of 40/37 ka, while level 17 at Trou Walou could be about the same age (Bonjean 2011; Pirson et al. 2011). At the same site, occupation CII-4 is dated by ESR to 45,000 to 50,000.

In Germany, the situation is more dichotomous. No Lower Pleniglacial human occupations have yet been discovered. During the Middle Pleniglacial, 94 occupation levels attributed to the “Mousterian with a Micoquian Option” are recorded for the 60 to 43 ka time bracket (Richter 2016), if we adopt the “short chronology” of the Micoquian put forward by Richter. The “long chronology” of this facies places a number of these sites in the Early Weichselian Glacial (Conard and Fischer 2000). In this case, only about twenty archaeological levels are recorded for the final phase of the Middle Paleolithic. This seems to end rather suddenly with the disappearance of Neanderthals at about 43 ka (Richter 2016), which is slightly earlier than in Belgium and northern France (Locht 2018).

In these three geographic areas, the cultural variability of the last part of the Middle Paleolithic reflects the situation in the whole of Europe (Fig. 12). Cultural traditions comprise regional specificities which indicate the identity of groups and affiliation to territories (Gabori 1976; Otte 2015).

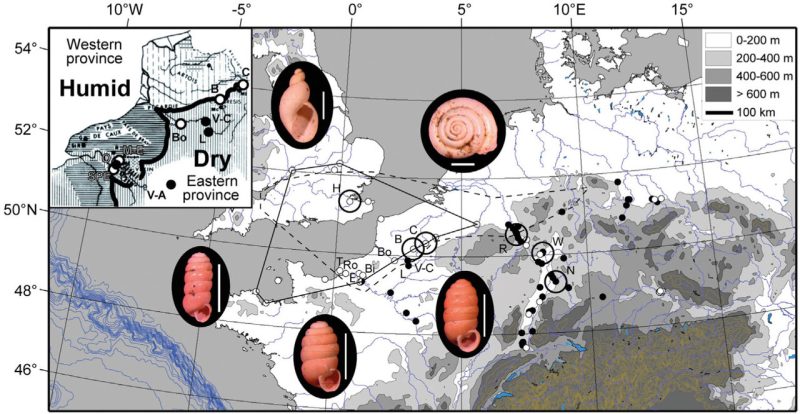

A difference in site density emerges between Belgium and northern France, on the one hand, and Germany, on the other, for the Lower and Middle Pleniglacial (Fig. 1). This may be partially explained by the malacological analysis of the Upper Pleniglacial loess sequences. This brings to light two climate-sedimentary domains (Lautridou and Sommé 1974; Moine 2014): one to the west, around the Channel and in Belgium, with a cold and wet environment with little vegetation, thus undoubtedly with few herbivores; and the other to the east, with a hillier landscape with more vegetation and a drier climate (Fig. 13). For the Middle Pleniglacial, the malacofaunal record is less abundant, but the scenario seems to be identical (Moine 2014). If we extrapolate from this, it is possible that the climatic conditions in northern France, beside the Atlantic coast, were cold and wet during much of the Middle Pleniglacial, and thus not conducive to human occupation. Again, humans may only have been present during the short interstadial phases. These climatic conditions could explain the disparity between the archaeological record of Belgium and northern France and that of Germany, for example.

At the end of the Middle Pleniglacial, the transition between the Middle Paleolithic and the Upper Paleolithic in northern Europe is characterized by the emergence of the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanovician transition facies, which extends from Poland to Great Britain (LRJ; Flas 2011). Two sites are recorded in central Germany (Ranis 2 and Zwergloch), and two in Belgium (Spy and Goyet). This cultural facies is unknown in southern Germany, where the Aurignacian gives way directly to the Middle Paleolithic (Richter 2016).

In spite of the wealth and accuracy of the sedimentary record of northern France, and clear interpretations, no transition facies has been identified in this region. Curiously, Chatelperronian or Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanovician influences have not been recorded in this zone. Therefore, the archaeological record of northern France does not contribute to discussions on the nature of the transition. On the contrary, it gives the impression that a rupture occurred between the two periods, with a shift from one world to another.

Conclusion

The contributions in this volume discuss whether the Rhine was a boundary or a corridor during the Middle Paleolithic. As a result of climatic fluctuations, the Rhine could have been an obstacle, in particular for movements from west to east. The Ferrassie-type Mousterian was identified to the west of the Rhine during MIS 7 (Rheindahlen B3, Maastricht, Biache-Saint-Vaast, etc.), but not to the east of the river. The same applies to MIS 7 and MIS 5 assemblages with laminar debitage, which are confined to the west of the river.

In the three geographic areas of interest here, the Middle Paleolithic emerges during MIS 8 with the onset of Levallois debitage, but few human occupations have been recorded during this Pleniglacial phase. During MIS 7, a certain cultural unity seems to exist in northwest Europe with the presence of a Ferrassie-type Mousterian, but also assemblages with a laminar component occur here as well. Like for MIS 8, few occupation traces are recorded during MIS 6.

The recent discoveries of the sites of Caours and Waziers clearly show that Neanderthals were present in northern France during the Eemian (MIS 5e) and complete the archaeological landscape outlined for this period by the central European sites.

The beginning of the Weichselian Glacial is characterized by the presence of assemblages with a laminar component in northern France, Belgium and Germany. However, the variability of Middle Paleolithic lithic assemblages is best expressed during MIS 4 and especially MIS 3. Site density is much higher in Germany than in Belgium and northern France. This may be a result of environmental factors, as the latter regions were much colder and wetter due to their proximity to the Atlantic coast.

During this period, and probably during earlier phases, the presence of a Keilmessergruppen-type facies in eastern France (south of Burgundy) implies that the Rhine/Rhone corridor may have played a role in cultural exchanges and migrations of Neanderthal populations from the center and the west of the continent.

Literature

Adam, A. 2002. Les pointes pseudo-Levallois du gisement moustérien Le Rissori à Masnuy-Saint-Jean (Hainaut, Belgique). L‘Anthropologie 106: 695–730.

Ameloot-Van Der Heijden, N., C. Dupuis, N. Limondin, A. V. Munaut, J. J. Puisségur. 1996. Le gisement paléolithique moyen de Salouël (Somme, France). L’Anthropologie 100 (4): 555–573.

Antoine, P., N. Limondin-Lozouet, P. Auguste, J.-L. Locht, B. Galheb, J.-L. Reyss, E. Escude, P. Carbonel, N. Mercier, J.-J. Bahain, C. Falguères, and P. Voinchet. 2006. Le site de Caours (Somme / France): Mise en évidence d’une séquence de tuf contemporaine du dernier interglaciaire (Eemien) et d’un gisement paléolithique associé. Quaternaire 17 (4): 281–320.

Antoine, P., E. Goval, G. Jamet, S. Coutard, O. Moine, D. Hérisson, P. Auguste, G. Guérin, F. Lagroix, E. Schmidt, V. Robert, N. Debenham, S. Mezner, and J.-J. Bahain. 2014. Les séquences loessiques pléistocène supérieur d’Havrincourt (Pas-de-Calais, France): stratigraphie, paléoenvironnements, géochronologie et occupations paléolithiques. Quaternaire 25 (4): 321–368.

Bodu, P., H. Salomon, M. Leroyer, H.-G. Naton, J. Lacarrière, and M. Dessoles. 2013. An Open-Air Site from the Recent Middle Palaeolithic in the Paris Basin (France): Les Bossats at Ormesson (Seine-et-Marne). Quaternary International 331: 39–59.

Boëda, E., S. Bonilauri, J. Connan, D. Jarvie, N. Mercier, M. Tobey, H. Valladas, H. al Sakhel, and S. Muhesen. 2008. Middle Palaeolithic Bitumen Use at Umm el Tlel around 70 000 BP. Antiquity 82: 853–861.

Bosinski, G. 1967. Die mittelpalaolithischen Funde im westlichen Mitteleuropa. Monographien zur Urgeschichte. Fundamenta A/4. Köln/Graz.

Bosinski, G. 1995. Palaeolithic Sites in the Rhineland. In Quaternary Field Trips in Central Europe. Vol. 2, ed. by W. Schirmer, pp. 931–999.

Bosquet, D., P. Jardon Giner, and I. Jadin. 2004. L‘industrie lithique du site paléolithique moyen de Rémicourt “En Bia Flo” (Province de Liège, Belgique): Technologie, tracéologie et analyse spatiale. In Actes du XIVème Congrès UISPP, Université de Liège, Session 5, Le Paléolithique moyen, Sessions générales et posters. BAR International Series 1239: 257-274.

Conard, N. J. 1992. Tönchesberg and its position in the Palaeolithic prehistory of northern Europe. Monographien Band 20, römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum.

Conard, N. J., and D. S. Adler. 1996. Wallertheim horizon D: an example of high resolution archaeology in the Middle Palaeolithic. Quaternaria Nova: 109–125.

Conard N.J., and B. Fischer, 2000. Are they recognizable cultural entities in the German Middle Palaeolithic? In Toward Modern Humans: Yabrudian and Micoquian, 400 – 50kyears ago, ed. by A. Ronen and M. Weinstein-Evron. BAR International Series 850: 7–21.

De Loecker D., 2004. Beyond the site. The saalian archaeological record at Maastricht-Belvédère (The Netherlands). Analecta Praehistorica Leidensia 35/36, University of Leiden.

Dignef, A. 2013. La pensée et le mouvant. La frontière du Rhin dans les Commentaires de César. Revue belge de philologie et d‘histoire, tome 91. Histoire médiévale, moderne et contemporaine Middeleeuwse, moderne en hedendaagse geschiedenis: 1123–1142.

Di Modica, K., M. Toussaint, G. Abrams, and S. Pirson. 2016. The Middle Palaeolithic from Belgium: Chronostratigraphy, territorial management and culture on a mosaic of contrasting environments. Quaternary International 411: 77–106.

Faivre, J.-P., B. Maureille, P. Bayle, I. Crèvecoeur, M. Duval, R. Grün, C. Bemilli, S. Bonilauri, S. Coutard, M. Bessou, N. Limondin-Lozouet, A. Cottard, T. Deshayes, A. Douillard, X. Henaff1, C. Pautret-Homerville, L. Kinsley, and E. Trinkaus. 2014. Middle Pleistocene Human Remains from Tourville-la-Rivière (Normandy, France) and Their Archaeological Context. PlosOne 9 (10): 1–13.

Flas, D. 2011. The middle to upper Palaeolithic transition in northern Europe: the Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician and the issue of acculturation of the last Neanderthals. World Archaeology 43 (4): 5499–5514.

Frick J. A., and H. Floss. 2017. Analysis of bifacial elements from Grotte de la Verpilliére I and II (Germolles, France). Quaternary International 428 : 3–25.

Gábori M. 1976. Les civilisations du Paléolithique moyen entre les Alpes et l’Oural. Esquisse historique. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Goval, E., and J. L. Locht. 2009. Remontages, systèmes techniques et répartitions spatiales dans l’analyse du site weichselien ancien de Fresnoy-au-Val (Somme, France). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 106 (4): 653–678.

Haesaerts, P., C. Dupuis, P. Spagna, F. Damblon, S. Balescu, P. Lavachery, S. Pirson, and D. Bosquet. 2019. Révision du cadre stratigraphique des assemblages Levalloisissus des nappes alluviales du Pléistocène moyen dans le bassin de la Haine (Belgique). Préhistoire de l’Europe du Nord-Ouest. Mobilités, climats et identités culturelles. In XXVIIIe Congrès préhistorique de France, Amiens – 4 juin 2016. Société préhistorique française 1: 179–199.

Heim, J., J. P. Lautridou, J. Maucorps, J. J. Puisségur, J. Sommé, and A. Thévenin. 1982. Achenheim: une séquence-type des loess du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur. Bulletin de l’Association française pour l‘étude du Quaternaire 19 (2-3): 147–159.

Heinzelin, J. de, and P. Haesaerts. 1983. Un cas de débitage laminaire au Paléolithique ancien: Croix-l’Abbé à Saint-Valéry-sur-Somme. Gallia Préhistoire 26 (1): 189–201.

Hérisson, D., J.-L. Locht, L. Vallin, L. Deschodt, P. Antoine, P. Auguste, N. Sévêque, N. Limondin-Lozouet, A. Gauthier, G. Hublin, B. Masson, B. Ghaleb, and C. Virmoux. 2017. Eemian: What’s up on the Western front? Ou à l’ouest Rhin de nouveau? The Rhine during the Middle Palaeolithic: boundary or corridor?, May 2017, Sélestat, France. Poster.

Junkmanns, J. 1995. Les ensembles lithiques d’Achenheim d’après la collection de Paul Wernet. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 92 (1): 26–36.

Koehler, H., R. Angevin, O. Bignon, and S. Griselin. 2013. Découverte de plusieurs occupations du Paléolithique supérieur récent dans le Sud de l’Alsace. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 110 (2): 356–359;

Koehler, H., F. Wegmüller, J. Detrey, S. Diemer, T. Hauck, C. Pümpin, P. Rentzel, N. Sévêque, E. Stoetzel, P. Wuscher, P. Auguste, H. Bocherens, M. S. Lutz and F. Preusser. 2016. Fouilles de plusieurs occupations du Paléolithique moyen à Mutzig-Rain (Alsace): premiers résultats. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 113 (3): 429–474.

Kozłowski, J. K. 2001. Origins and Evolution of Blade Technologies in the Middle and Early Upper Palaeolithic. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 1 (1): 3–18.

Kozłowski, J. K. 2002. La Grande Plaine de l’Europe avant le Tardiglaciaire. In Préhistoire de la Grande Plaine du Nord de l’Europe. Les échanges entre l’Est et l’Ouest dans les sociétés préhistoriques, Actes du colloque Chaire Francqui interuniversitaire titre étranger (Université de Liège, 26 juin 2001), ed. by M. Otte and J. K. Kozłowski, pp. 53–65. Liège: ERAUL.

Kozłowski, J. K. 2006. Les Néandertaliens en Europe centrale. In Neanderthals in Europe, ed. by B. Demarsin and M. Otte, pp. 77–90. Liège: ERAUL 117.

Le Brun-Ricalens, F., G.Thill-Thibold, J. Thill-Thibold, T. Rebmann, G. Gazagnol, I. Koch, V. Stead-Biver, and F. Valloteau. 2013. Lellig “Mierchen-Mileker” Manternach, G.-D. de Luxembourg. Une occupation moustérienne de plein air entre Sûre et Moselle. Dossiers d’Archéologie XIV. Musée National d’Histoire et d’Art, Centre National de la Recherche Archéologique, Luxembourg.

Locht, J. L. (ed.). 2002. Le gisement de Bettencourt-Saint-Ouen (Somme, France): cinq occupations du Paléolithique moyen au début de la dernière glaciation. Documents d‘Archéologie Française 90. Paris: Maison des Sciences de l‘Homme.

Locht, J.-L. 2004. Le gisement paléolithique moyen de Beauvais (Oise). Contribution à la connaissance des modalités de subsistance des chasseurs de renne du Pléniglaciaire inférieur du Weichselien. PhD Thesis, Université Lille I.

Locht, J.-L. 2005. Le Paléolithique moyen en Picardie : état de la recherche. In : La Préhistoire ancienne. La recherche archéologique en Picardie : bilan et perspectives. Revue Archéologique de Picardie 3/4: 27–35.

Locht, J.-L. 2018. Chronologie, espaces et cultures: le Paléolithique moyen de France septentrionale. Habilitation à diriger des recherches, Université d’Aix-Marseille, vol. 1.

Locht, J.-L. 2019. La fin du Paléolithique moyen dans le Nord de la France. Quaternaire 4: 335–350.

Locht, J.-L., P. Antoine, J.-J. Bahain, N. Limondin-Lozouet, A. Gauthier, N. Debenham, M. Frechen, G. Dwrila, P. Raymond, D.-D. Rousseau, C. Hatté C., P. Haesaerts, and H. Metsdagh H. 2003. Le gisement paléolithique moyen et les séquences pléistocènes de Villiers-Adam (Val d’Oise, France): Chronostratigraphie, Environnement et Implantations humaines. Gallia Préhistoire 45: 1–111.

Locht, J.-L., D. Hérisson, P. Antoine, G. Gadebois, and N. Debenham. 2010. Une occupation de la phase ancienne du Paléolithique moyen à Therdonne (Oise, France): chronostratigraphie, production de pointes Levallois et réduction des nucléus. Gallia Préhistoire 52: 1–32.

Locht, J.-L., E. Goval, P. Antoine, S. Coutard, P. Auguste, C. Paris, and D. Hérisson. 2014. Palaeoenvironments and prehistoric interactions in northern France from the Eemian Interglacial to the end of the Weichselian Middle Pleniglacial. In Wild Things. Recent Advances in Palaeolithic and Mesolithic Research, ed. by F. W. F. by Foulds, H. C. Drinkhall, A. R. Perri, D. T. G. Clinnick, and J. M. P. Walker, pp. 70–78. Oxford: Oxbow Press.

Locht, J.-L., D. Hérisson, E. Goval, D. Cliquet, B. Huet, S. Coutard, P. Antoine, and P. Feray. 2016. Timescale, space and culture during Middle Palaeolithic in Northwestern France. Quaternary International 411: 129–148.

Marcy J.-L., P. Auguste, M. Fontugne, A.-V. Munaut, and B. Van Vliet-Lanoë. 1993. Le gisement moustérien d Hénin-sur-Cojeul (Pas-de-Calais). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 90 (4): 251–256.

Moine, O. 2014. Weichselian Upper Pleniglacial environmental variability in north-western Europe reconstructed from terrestrial mollusc faunas and its relationship with the presence/absence of human settlements. Quaternary International 337: 90–113.

Otte, M. 2015. Aptitudes cognitives des Néandertaliens. Bulletin du Musée d’Anthropologie préhistorique de Monaco 55: 15-40.

Otte, M., E. Boëda, and P. Haesaerts. 1990. Rocourt: industrie laminaire archaïque. Hélinium XXIX/1: 3–13.

Pop, E. 2014. Analysis of the Neumark-Nord 2/2 lithic assemblage: Results and interpretations. In Multidisciplinary studies of the Middle Palaeolithic record from Neumark-Nord (Germany), ed. by Gaudzinski-Windheuseur S. and W. Roebroeks, pp. 143–195. Veröffenlichtung des Landesamtes für Denkmalplege und Archäologie Saschen-Anhalt-Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte 69.

Richter, J. 2010. When did the Middle Palaeolithic begin? In Neanderthal Lifeways, Subsistence and Technology: One Hundred Fifty Years of Neanderthal Study, ed. By N. J. Conard and J. Richter, pp. 7–14. Springer.

Richter, J. 2016. Leave at the height of the party: A critical review of the Middle Palaeolithic in Western Central Europe from its beginning to its rapid decline. Quaternary International 411: 107–128.

Roebroeks, W., and B. Speleers. 2002. Last interglacial (eemian) occupation of the north european plain and adjacent areas. In Le Dernier Interglaciaire et les occupations humaines du Paléolithique moyen, ed. by A. Tuffreau, pp. 31–39. Publication du CERP 8, Villeneuve d’Asc.

Roebroeks, W. 2014. Terra Incognita: The palaeolithic record of northwest Europe and the information potential of the southern North Sea. Netherlands Journal of Geosciences – Geologie en Mijnbouw 93: 43–53.

Street M., T. Terberger, and J. Orschiedt, 2006. A critical review of the German Palaeolithic hominin record. Journal of Human Evolution 51: 551–579.

Thieme, H. 1997. Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany. Nature 385: 907–910.

Thieme, H., and S. Veil. 1985. Neue Untersuchungen zum eemzeitlichen Elefanten-Jagdplatz Lehringen, Ldrk. Verden. Die Kunde N.F. 36: 15–19.

Toussaint, M., P. Semal, and S. Pirson. 2011. Les Néandertaliens du bassin mosan belge: bilan 2006-2001. In Le Paléolithique moyen en Belgique. Mélanges Marguerite Ulrix-Closset, ed. by M. Toussaint, K. Di Modica and S. Pirson. ERAUL 128.

Tuffreau, A. 1982. The transition Lower/Middle Palaeolithic in Northern France. In The Transition from Lower to Middle Palaeolithic and the Origin of the Modern Man, ed. by A. Ronen, pp. 137–149. BAR International Series 151.

Tuffreau, A., and J. Sommé. 1988. Le gisement paléolithique moyen de Biache-Saint-Vaast (Pas de Calais) T.1. Mémoires de la Société préhistorique française 21.

Tuffreau, A., S. Révillion, J. Sommé, and B. Van Vliet-Lanoë. 1994. Le gisement paléolithique moyen de Seclin (Nord). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique Française 91 (1): 23–46.

Valladas, H., N. Mercier, C. Escutenaire, T. Kalicki, J. K. Kozłowski, V. Sitlivy, K. Sobczyk, A. Zieba, and B. Van Vliet-Lanoë. 2003. The Late Middle Palaeolithic Blade Technologies and the Transition to the Upper Palaeolithic in Southern Poland: TL Dating Contribution. Eurasian Prehistory 1 (1): 57–82.

Van Der Sloot P., P. Haesaerts, and S. Pirson. 2011. Les sites du Mont Saint-Martin (Liège). In Le Paléolithique moyen en Belgique. Mélanges Marguerite Ulrix-Closset, ed. by M. Toussaint, K. Di Modica, and S. Pirson. ERAUL 128: 385–393.

Von Berg, A., S. Condemi, annd M. Frechen. 2000. Die Schädelkalotte des Neandertalers von Ochtendung/Osteifel – Archäologie, Paläoanthropologie und Geologie. Eiszeitalter und Gegenwart 50: 56–58.

Wagner, G. A., M. Krbetschek, D. Degering, J.-J. Bahain, Q. Shao, C. Falguères, P. Voinchet, J.-M. Dolo, T. Garcia, and G. P. Rightmire. 2010. Radiometric dating of the type-site for Homo heidelbergensis at Mauer, Germany, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 19726–19730.

Wenzel, S. 2007. Neanderthal presence and behaviour in Central and Northwestern Europe during MIS 5e. In The climate of past interglacials, ed. by F. Sirocko, M. Claussen, M. Goñi, and T. Litt, pp. 173–193. Amsterdam: Elsevier.